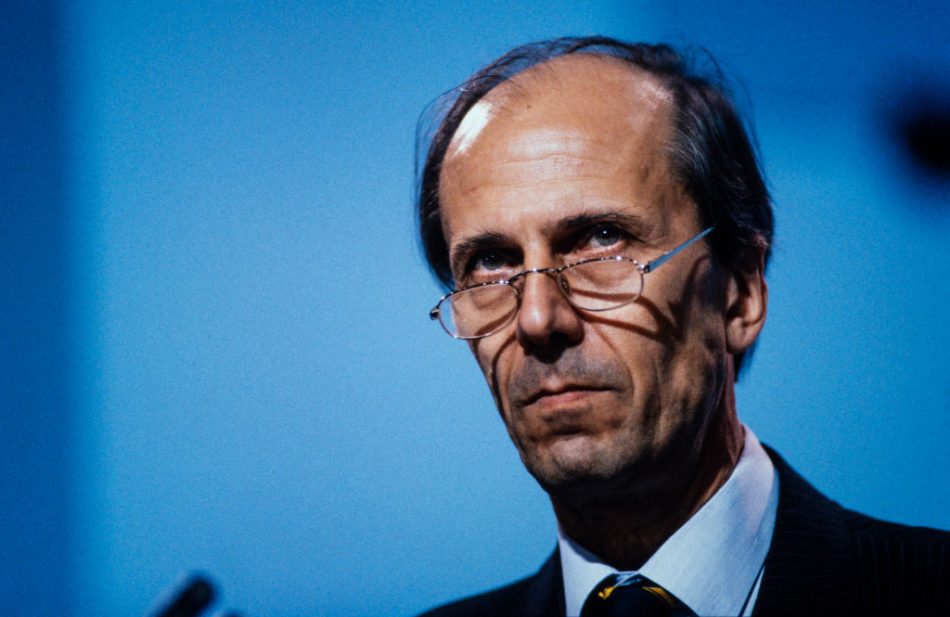

Norman Tebbit, the longtime keeper of the Thatcherite flame, has died at the age of 94. His career in public life spanned more than 50 years, from his election to the Epping constituency in 1970 to his retirement from the House of Lords in 2022. A Monday Club member and ardent right winger, he might have been destined to spend his career in relative backbench obscurity. But the election of Margaret Thatcher in 1975 proved to be the making of his political career.

Tebbit proved his mettle to the Iron Lady in the trade union battles of the 1970s. His criticisms of the closed shop – whereby members of a profession had to belong to a union – prompted Michael Foot on one occasion in 1978 to brand him a ‘semi-house-trained polecat’, an epithet he wore with pride. After the Tory triumph in May 1979, Thatcher, unsurprisingly, handed Tebbit the brief of Under-Secretary at the Ministry of Trade. Two years later came the call to join the cabinet.

Thatcher had tired of the doveish attitude of Jim Prior, her Employment Secretary, towards curbing trade union power. She replaced him with Tebbit, heralding a decisive shift to a tougher approach. His 1982 Employment Act restricted the closed shop and made unions liable for civil damages if they committed unlawful acts. In his memoirs, Tebbit called it his ‘greatest achievement in government.’ It was at Employment that he made his famous public remark too. He attacked the 1981 riots in London and Liverpool by noting his father’s reaction to being made unemployed: ‘He got on his bike and looked for work.’ Norman ‘on yer bike’ Tebbit was born.

In the 1983 election, Tebbit was the second most prominent Conservative on radio and television broadcasts, after Thatcher. After a successful two years, promotion was inevitable. He received his reward in October that year, with the brief of Trade and Industry, after Thatcher’s initial bid to make him Home Secretary had been vetoed by Willie Whitelaw. He launched one of the first major privatisations by selling off British Telecom. But Tebbit’s time at the DTI was shadowed by the defining moment of his political career: his injury in the Brighton bomb at that year’s party conference. The scenes of Tebbit being pulled from the wreckage of the Grand Hotel are some of the most searing images of 1980s politics. His beloved wife, Margaret, was left permanently disabled.

Like much of his career, his subsequent spell as Tory chairman from 1985 to 1987 was marked by controversy and drama. He disbanded the Federation of Conservative Students, repeatedly berated the BBC for its coverage and clashed with Thatcher over what polling showed was the ‘TBW’ factor in the upcoming election: That Bloody Woman. There was a memorable spat with David Young in the 1987 campaign, on ‘wobbly Thursday’ after a rogue poll showed the Tories down to just a 2 per cent lead. Despite Young’s claim that ‘Norman, listen to me, we’re about to lose this fucking election,’ it proved to be a triumphant success as the Tories were returned with a majority of 102.

Yet despite a third successive term, Tebbit decided that now was the time to return to the backbenches. He had promised Margaret he would retire at the beginning of the campaign and he duly kept to his word. ‘He’ll carry the scar of that Brighton bombing all his life’, remarked Thatcher to her friend Woodrow Wyatt. She bitterly regretted the loss of such a close like-minded ally. Tebbit was one of a series of men tipped to replace the Iron Lady at some point in the 1980s, like John Moore and Cecil Parkinson. That he should leave the cabinet said much about his love for his wife.

Like much of his career, his subsequent spell as Tory chairman from 1985 to 1987 was marked by controversy and drama

He formed an unlikely alliance with Michael Heseltine in 1988, when they campaigned together for the abolition of the Inner London Education Authority. But two years later, they were very much opponents once again, after Geoffrey Howe triggered the events which were to lead to the Iron Lady’s downfall. Thatcher’s biographer, John Campbell, noted that Tebbit proved to be her ‘most visible cheerleader.’ He urged her to fight on, even after the cabinet turned against her. In her memoirs, Thatcher bemoaned how she never had ‘six men and true’ during her time in office. But Tebbit was certainly one of the few on which she could rely.

Like Thatcher, Parkinson and so many other giants of the 1980s, Tebbit stood down at the 1992 election, making way for Iain Duncan Smith – another Chingford right-winger. Ennobled, his most memorable highlight in the Lords came when he savaged John Major at the 1993 party conference over Maastricht. He proved to be an awkward opponent for most of Thatcher’s successors and regularly criticised David Cameron for his modernising agenda. His speech in the 2013 debate following Baroness Thatcher’s passing was among the finest that made that day.

Pugnacious, outspoken, clever, brave: Norman Tebbit was the upwardly mobile icon of Thatcher’s Britain.

Comments