One of the members of the government’s HS2 Growth Taskforce is remembering the first time he went to a gay club. ‘There was a club in Coventry that was only open on a Sunday night, at the Quadrant, and a mate of mine said, “There’s a DJ there who plays some fantastic music that I know you’ve never heard, so why don’t we go down?” It was a gay club, or a queer’s club as it was known then. I loved it. Oh, I loved it. I couldn’t believe that blokes were dancing with each other. The music was awesome.’

A few years later, in the early 1980s, he ‘lived for six months with a gay mate, and we were out at gay clubs every night of the week, but it was great for me because I was watching the marketplace from a punter’s point of view. New Order’s “Blue Monday” was just happening, and I was [thinking]: “Look at this, there’s something going on here.” I had a good four to five months watching the marketplace as an insider almost.’

This member of the HS2 Growth Taskforce is not, unsurprisingly, one of the great and the good of industry. It’s Pete Waterman, the record producer and songwriter whose songs — co-written and co-produced by his colleagues Mike Stock and Matt Aitken, and recorded by an array of artists of varying degrees of actual talent — were the sound of the British charts from 1984 until the end of the decade. Stock Aitken Waterman might have sounded like a moderately successful regional accountancy firm, but they were as all-conquering as Holland-Dozier-Holland, the Motown songwriting team who inspired their own brand name. They had more than 100 UK top 40 hits, including 13 number ones, selling 40 million records, and became millionaires in the process — 50 of the hits are gathered in a new compilation called The Hit Factory Ultimate Collection. Then Waterman did it all over again, as the mastermind behind Steps, the Poundland Abba, who had 14 top 10 hits.

None of it would have happened without the gay clubs. Stock Aitken Waterman made its name as a guerrilla production team, taking Hi-NRG music into the mainstream. ‘We weren’t brazen enough to think we could take on EMI or Warner or the big companies. That never even came into our thoughts. We just knew the major record companies were not focused on a market I knew well and loved — the gay dance market. They weren’t interested.’

The breakthrough came in 1984, with hits by Hazell Dean and Divine, the drag queen star of John Waters films. (‘When we played it to the record company, they went, “What’s this? It’s too good. He’s singing. We don’t want him to sing. He’s Divine — he’s got to shout, that’s what he does.” So we had to call the airport and get him in a taxi back from Heathrow, get him to the studio, have him shout it all the way through once, then put him in the cab back to Heathrow.’) The following year, ‘You Spin Me Round (Like a Record)’ by Dead or Alive was their first No. 1, and their ascension was complete.

‘When I heard “Spin Me Round”, all I heard was Pete Burns on a terrible tape recorder going’ — Waterman here impersonates Burns’s mannered baritone — ‘You spin me right round, baby, right round like a record, baby, right round. That to me was the song. The hook is enough. I knew the song was dramatic enough. And then you put Pete on top of that with the eyepatch and the hair — the minute he’s on Top of the Pops, you know cabbies are going to be saying, “Did you see that geezer? I thought it was a woman.” Thank you!’

Waterman is obsessed by songwriting quality. He thinks modern hits, put together by separate songwriting teams, each responsible for a different element, prove songwriting by committee doesn’t work. He claims he ‘never had a hit with a bad record’, and when I suggest that the Capital DJ duo Pat and Mick — the one with the mullet and the one with the blazer — made some that were no great shakes, he takes offence. ‘You may not like Pat and Mick, but it’s a good record. If it wasn’t a good record, people wouldn’t buy it.’ Which would make Dan Brown a great author, and the Transformers movies classics.

But then he accepts that what he did was always about commerce, not art (‘Oh, we wasn’t making anything else’), and that ‘William Shakespeare, we were not. We may have wrote a few plays. We took it serious, in the mode of what we did, but we weren’t Leonard Cohen or any artist of that ilk.’ But being proven hitmakers did result in SAW’s strangest job of all, recording three songs with the heavy-metal band Judas Priest in 1988, of which only a brief snippet — a minute or so of a cover of the Stylistics’ ‘You Are Everything’ — has ever surfaced, on YouTube. ‘Their manager said: “Bury it. It’s a number one record. And it’s the worst thing that could happen to your career.” They’d have lost the belt-buckle crowd.’

Waterman first realised the power of songs as a kid, in the church choir. (‘If you’re going to be frightened of God, be frightened of Him, for goodness sake! Don’t sing about flowers and rainbows, sing about the walls of Jericho coming down on you and killing you if you’re going to not believe in God. Don’t bloody pussyfoot around!’) And in retrospect, he says, church services gave him an understanding of the market: ‘The vicar’s putting on hymns that are meaningful. But no one knows ’em and no one can sing ’em. So I learned very early that the public were not as gullible as people thought they were. It didn’t matter what the vicar thought they should be doing. They would only like what they were familiar with. When they were certain of a song, they would give it rice.’

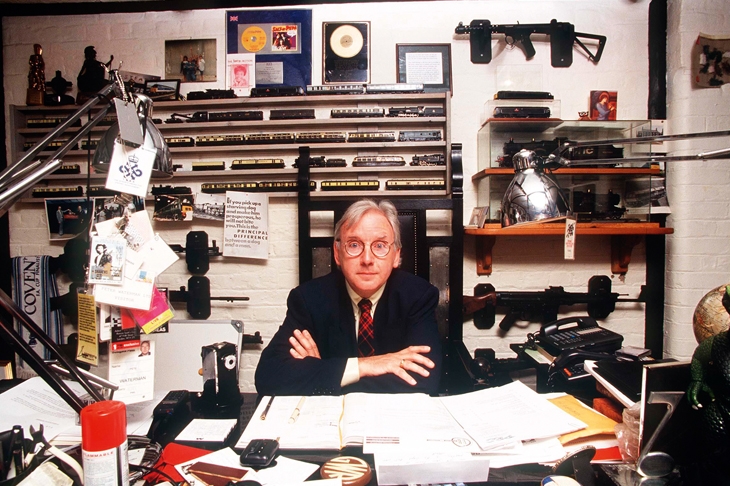

There is very little, in fact, upon which Waterman does not have strong and certain opinions. Which brings us, naturally, to the railways. Waterman worked on them as a youth, and he’s a dedicated rail enthusiast — he invested his music millions in reestablishing London & North Western Railway, maintaining rolling stock and renovating vintage engines. Hence the call to the HS2 Growth Taskforce. The railways are better than ever before, and should on no account be renationalised, he says.

Then why do people think they’re so terrible?

‘’Cos journalists like you keep going on about it! You never fucking say anything good about it!’ He proceeds to give me a lesson in rail economics and capacity, the scheduling of trains through Warrington and Crewe (‘We call Crewe the Crucible — you’ve got to get through all the reds to reach the colours’), and how HS2 will bring people to the north and connect Manchester and Liverpool properly for the first time. It’s delivered every bit as fervently as his defence of Pat and Mick, or his disdain for pop stars who want to be considered serious artists.

Get Pete Waterman to backtrack on anything? I should be so lucky.

Comments