For those of us not into Oasis in the 90s, the past month’s mania over their reunion has been baffling. Songs like ‘Wonderwall’ and ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’ may have hit the spot but as individuals Oasis seemed far from engaging. As John Harris said in his book The Last Party: Britpop, Blair and the Demise of English Rock, ‘It was difficult to think of any group whose career had combined stratospheric success with such stubbornly limited horizons.’

Liam’s wild man antics were risible and often pointlessly insulting

The band didn’t appear to read or have interests outside music, Liam’s wild man antics were risible, and they were often pointlessly insulting. Even Noel, the nice brother, received a Brit award from Michael Hutchence with the words: ‘Has-beens shouldn’t present f***in’ awards to gonna-bes’; on another occasion, he wished publicly that Blur’s Alex James and Damon Albarn would ‘catch AIDS and die.’

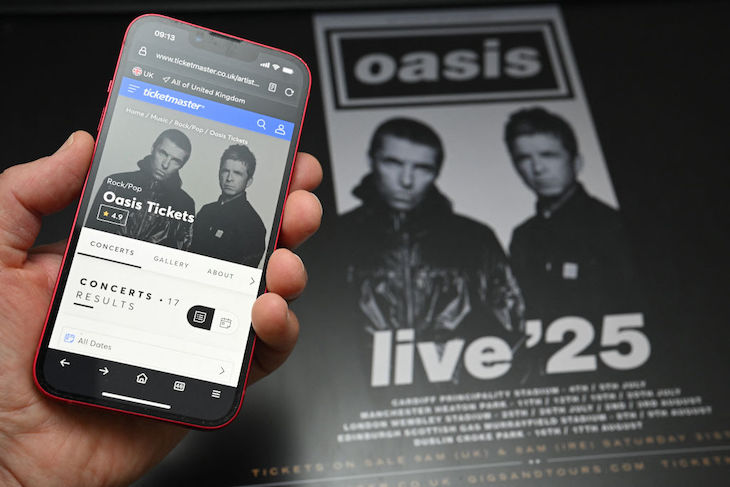

‘Why do we care so much about Oasis?’ asked a recent headline on the BBC website. Many of us will be scratching our heads.

But, leaving aside Jarvis Cocker’s Pulp (to whom whole paeans could be written), there is a trio of 90s bands equally – if not more – deserving of our interest. They pumped out deathless hit after deathless hit, and between them raged a feud just as venomous as that of Oasis vs. Blur, and a lot more convincing too. This story had at its centre a young woman whose cultural influence seemed everywhere in the 1990s – as she exploded onto the scene, catalysing events and songs, before, a few years later, vanishing almost completely.

That woman was Justine Frischmann, lead singer of the band Elastica, and before that, lover of Suede’s Brett Anderson. Anderson met Frischmann – her mother a second-generation Russian-Jewish émigre, her Hungarian father an orphaned survivor of Auschwitz – at UCL, when she was studying architecture and Anderson, ‘a weird little provincial twig’ from Haywards Heath, was doing a degree in town-planning. Frischmann and Anderson, musicians both, clicked and became a couple almost immediately: ‘Brett’s always had this kind of tragic romanticism,’ said Frischmann, ‘and it’s really lovely, it makes you think Trellick Tower and the Westway are beautiful.’ Soon they were in a band together, with Anderson singing, Mat Osman playing bass and Frischmann (along with the legendary, 19-year-old Bernard Butler) on guitar.

Yet before the group achieved any kind of breakthrough, fate intervened to break it all up. Frischmann met a musician from another up-and-coming band, a young man called Damon Albarn, who quickly began laying siege to her.

‘He took it upon himself to track me down,’ explained Frischmann. ‘I’d never been pursued like that…I was quite intrigued.’ By February 1991, she was going out with Albarn, and a few months later left Suede altogether, perhaps doing Anderson a favour in the process.

‘It wasn’t until all the ugliness happened and I ran off with Damon that he got enough of a demon in him,’ said Frischmann, ‘a reason to get his own back on the world.’ Anderson seems to have agreed: ‘I began to realise that expressing weakness and expressing pain could be wonderfully cathartic.’

Before they even had a record out, Suede, with their glimmering songs of urban alienation, drug addiction and ‘broken scruffy life’, were being heralded by Melody Maker as the ‘Best New Band in Britain.’ Rock writer Stuart Maconie recalled receiving the group’s demo at NME – ‘I remember the prickling sensation in the back of the neck’ – and thinking, ‘Oh my God. This band have come to save us.’ Their debut album Suede was the fastest-selling, at the time, in British history. Deservedly too: songs like ‘Drowners’, ‘So Young’ and ‘Pantomime Horse’ seem not so much influenced by The Smiths or David Bowie as the songs they forgot to write.

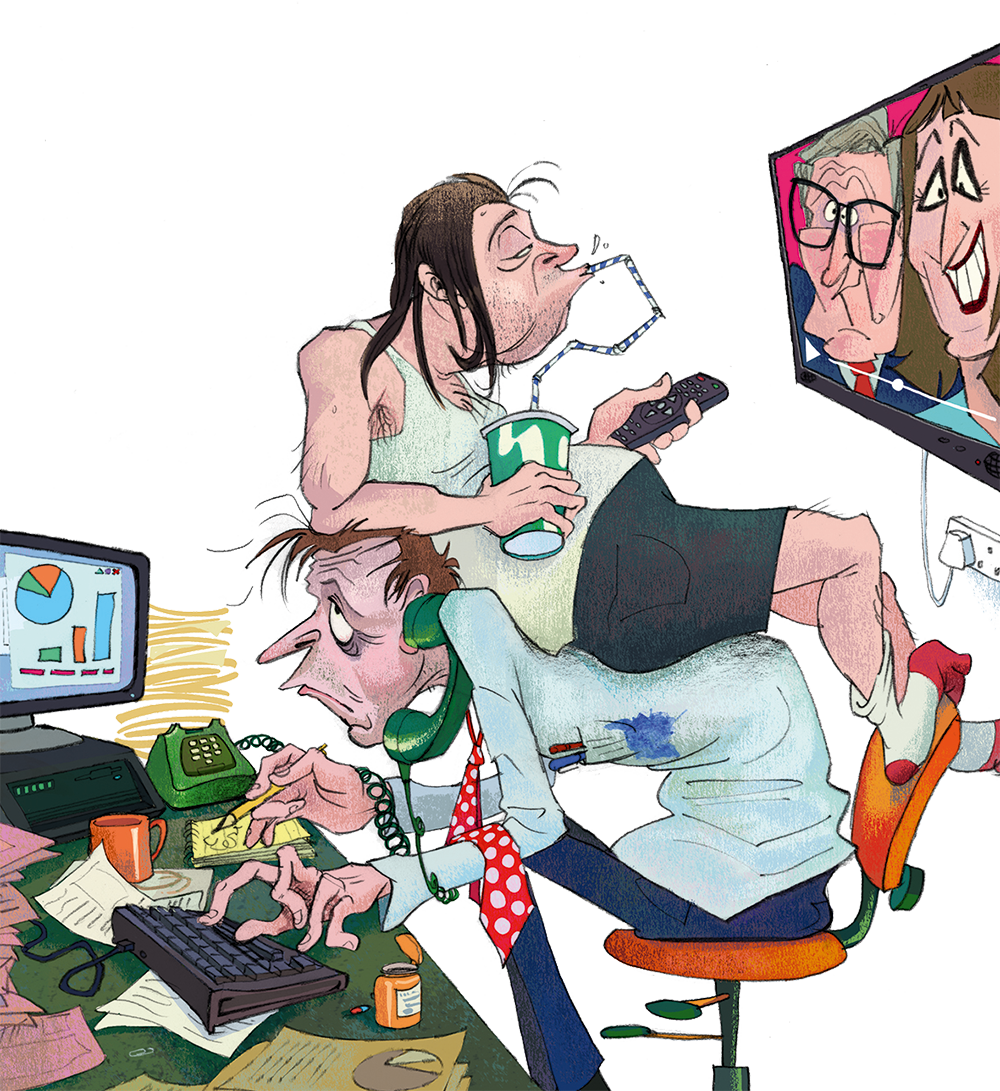

Meanwhile Blur, Albarn’s band, was going through a metamorphosis of their own. Frischmann had taken Albarn’s listening habits in hand – ‘He had about three tapes… He didn’t have a clue; he didn’t buy records’ – and was dating the singer when Blur, homesick on a disastrous US tour, began to embrace their Britishness.

‘I just started to miss really simple things,’ said Albarn, ‘I missed people queuing up in shops. I missed people saying “goodnight” on the BBC… I missed everything about England.’ The stage was now set for Blur’s series of distinctly British hits: ‘Sunday Sunday’, ‘Girls and Boys’, ‘For Tomorrow’, and ‘Country House’ among others – and for an album, Parklife, that went platinum four times over.

Listen to Blur and ask yourself whether the recent Oasis-mania isn’t missing a trick or two

Yet despite this success, Frischmann’s abandonment of Anderson for Albarn had released a great torrent of bad blood. Both men, famously competitive, sniped at each other throughout the decade.

‘I knew that my moment for vengeance would come…,’ Albarn was quoted in a French magazine in 1994. ‘I wanted to prove to myself that I could dethrone Brett and his group of cretins.’ Later Anderson was to accuse Blur of being ‘obsessed by their career,’ while Suede had ‘always been obsessed by their music. That’s the difference.’ Albarn publicly attacked Anderson for taking heroin, Anderson called him a ‘talentless public schoolboy who’s made a career out of being patronising to the working classes.’

When, in the late 1990s, Frischmann tried to organise a rapprochement between the two, predictable disaster followed: ‘It was like a cat and dog meeting each other…. I got Brett out of there within two minutes… they really needed to hate each other.’

Throughout it all, you get a strange sense of symbiosis: that both bands’ tumultuous successes were helped in no small degree by their mutual loathing. In 1995, Blur won four Brit awards, for best album, best single, best band and best video. Suede’s album Coming Up, the following year, had five hit singles and went straight into the charts at number one. ‘Revenge,’ laughed Anderson, ‘is really underrated as a motivation.’

Meanwhile, Frischmann herself had proved no slouch, forming her own band Elastica with guitarist Donna Matthews and bassist Annie Oakley. From the outset, the response to the group had been rapturous.

‘Oh my God, this is what you dream about,’ remembered Mike Smith, the record executive who signed them. ‘Loads of attitude. Super sharp lyrics, four of the coolest kids I’ve met in my life and songs to die for.’ Journalist Miranda Sawyer was equally struck: ‘There was something so amazing, as a woman, to see these three women step forward with their guitars.’ Their songs – mostly about two minutes long, punchy as hell and about anything from having a boyfriend with erectile dysfunction to the absurdities of the music media machine – brought them a string of hits and took them to number one in the UK albums chart. On a twelve-month tour of the UK, US, Europe and Australia, Elastica played a staggering 102 shows, before the inevitable burnout and break-up followed

By around the end of the decade it had virtually collapsed for them all in a welter of drugs and clashing personalities – Frischmann broke with Albarn and Elastica guitarist Donna Matthews in the very same week – and the party, effectively, was over. Though Suede and Blur continued to produce albums, Frischmann went off to pursue an art career in America (she’s now married to a professor of meteorology and lives in California). The momentum, for all of them, had wound down and the zeitgeist moved on elsewhere. Frischmann alone seems to have realised – in that hoary rock n’ roll cliché – that it was better to burn out than fade away.

But go off and listen to them, to the spectral pathos of Suede’s ‘The Next Life’, the knock-out blow of Elastica’s ‘Stutter’ or the monumentally moving ‘This is a Low’ from Blur and ask yourself whether the recent Oasis-mania isn’t missing a trick or two. What talent. What characters. What a story. What style. And why hasn’t some enterprising film-producer somewhere made a movie about it?

Comments