Timothy Clifford enjoys the British Museum director’s tour of human history – but misses the beauty of Kenneth Clark’s ‘Civilisation’

‘Mission Impossible’ is how Neil MacGregor, in the preface to this book, describes the task set for him by Mark Damazer, controller of BBC Radio 4. MacGregor was to introduce and interpret 100 objects chosen by colleagues from the British Museum and the BBC. They had to range in date from the beginning of human history, around two million years ago, right up to the present day.

The objects were intended to cover the whole world equally, as far as it is possible. They would necessarily include the humble things of everyday life as well as great works of art. As five programmes were to be broadcast each week, objects would be grouped in clusters of five, ‘spanning the globe at various points in time and looking at five snapshots of the world through objects of that particular date’.

Because the BM collection encompasses the whole world — and the BBC broadcasts to every part of it — experts and commentators from all over the world would be invited to join in. The massive Radio 4 series has now run its course, to considerable acclaim, and now we have the accompanying book, neatly timed for the Christmas market.

The rollercoaster sweep of history starts with a stone chopping tool discovered by Louis Leakey in the Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, which dates from 1.8 to 2 million years ago, and culminates, today, with a plastic torch made in China operated by solar power.

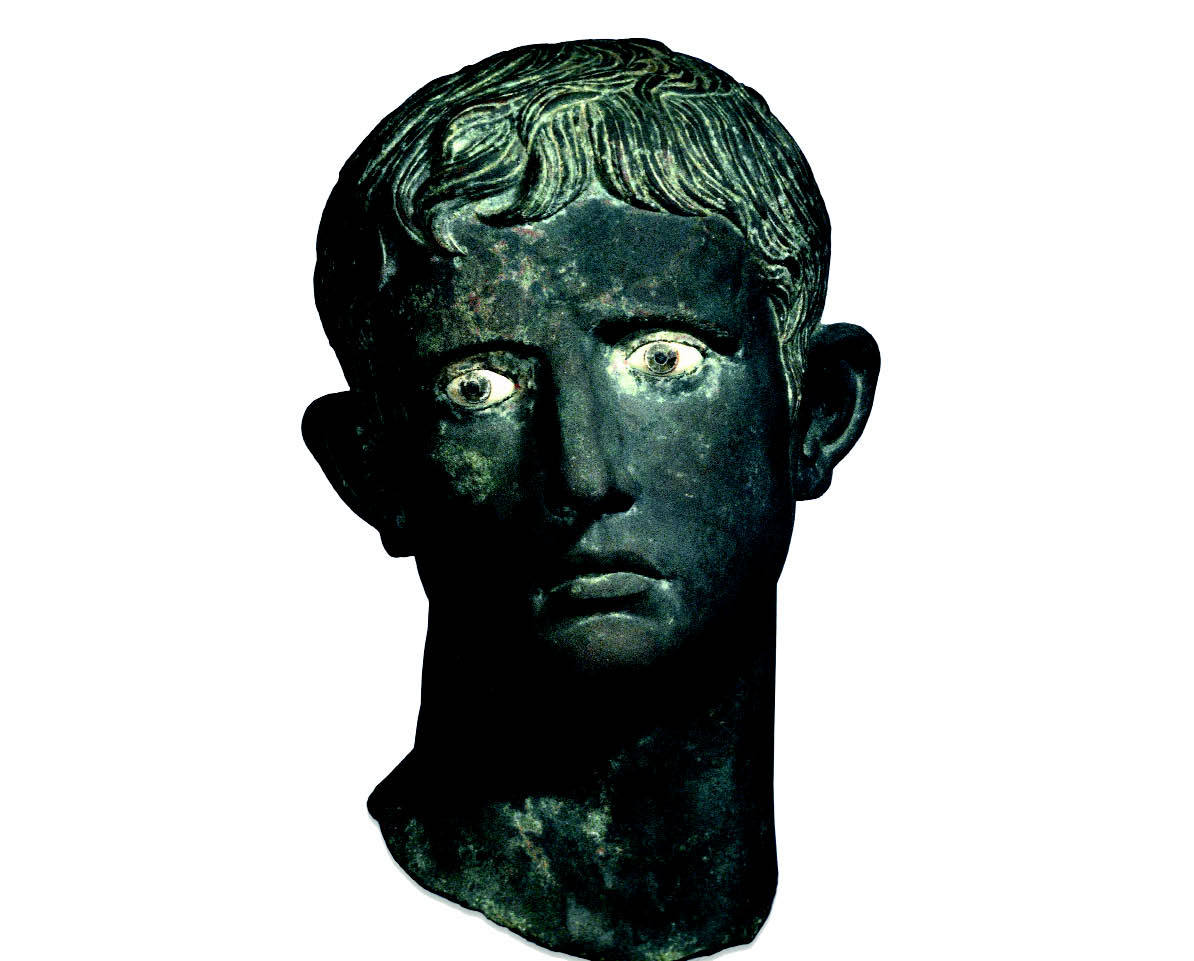

These are demonstrably highly significant objects in the development of mankind anthropologically, but they are a far cry from the visual delights encompassed in Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation series conceived for BBC television and also accompanied by a popular book. It may seem a little unfair to make such comparisons, but both MacGregor and Clark were directors of the National Gallery, sharing a passionate delight in the educational and spiritual value of artefacts or, more often in MacGregor’s case, things. Clark, despite his Wykhamist education, aspired to be a right-leaning grandee, while MacGregor articulates throughout his book and radio series his diplomatic philosophy of the liberal left. Whether it was at the urging of the BBC, or MacGregor’s choice, we had illuminating comments by Richard Rogers on the Stone Seal from Harappa in the Indus Valley, Paddy Ashdown on the Lachish Reliefs from Nineveh and Tony Benn on the North American Otter Pipe from Mound City, Ohio. On the other hand, we did hear from Boris Johnson — who really is a distinguished classicist — about the Bronze Head of Augustus from Meroë, Sudan.

Maybe I am being a little unkind, for the series also included some first-rate observations by many international scholars. The concept of this book is original, and entirely appropriate for the BM which was set up in the mid-18th century as a vast encyclopedia of knowledge that then encompassed the nuclei of both the Natural History Museum and the British Library, two collections whose loss, at least on a contiguous site in Bloomsbury, is still much regretted.

Certainly the objects chosen have resonances right down to our own time and do allow us to see, and understand in context, the big issues of the day — war, belief, nationalism, smoking, sex, personal identity, trade, economics. Discussing such subjects is where MacGregor becomes an excellent, even inspired storyteller. Elegantly, he slips in references to Beowolf, The Thousand and One Nights, Coleridge, Shelley and George Herbert. He also obviously enjoys The Just-So Stories, and there are many undercurrents of them within his descriptive texts.

MacGregor’s insights and shrewd observations sometimes have a twist. Describing the late Roman silver hoard found at Hoxne, Suffolk, which included a pepper pot and spoon inscribed vivas in deo (‘May you live in God’ — a common Christian prayer), he points out, ‘Like pepper [Christianity] had come to Britain via Rome, but both survived the fall of the Roman Empire’. About the Roman Warren Silver Cup, with explicit scenes of gay love, he observes, ‘this object reminds us that the way societies view sexual relationships is never fixed’; or about the north American Otter Pipe:

The overturn of smoking in the Western World in the past 30 years has been an extraordinary revolution. What societies deem as pleasure is constantly and unpredictably negotiated.

In discussing the pair of Basse-Yutz Flagons found in Moselle, North-East France he observes:

The idea of a Celtic identity, although strongly felt and articulated today by many, turns out on investigation to be disturbingly elusive, unfixed, and changing. The challenge when looking at [such objects] is how to get past those distorting mists of nationalist myth-making.

Mary Wakefield in The Spectator (16 October) observed about MacGregor:

He’s charming and universally admired — but also enigmatic. What are his politics? What does he do for fun? Nobody seems to know. I left knowing less than ever about him. Listening to MacGregor on BBC Radio 4 telling A History of the World in 100 Objects, it occurred to me that his mysterious private life makes him ideal for the BM: he can tell the story of an object without his own intervening.

I would take issue with Mary Wakefield’s last observation. We know that MacGregor was brought up and educated in Glasgow where his father and mother were respectively a GP and a pharmacist. He read law at Edinburgh, practised at the bar, went to university in Paris and speaks French fluently. He was in Paris during the heady days of student unrest in 1968. He was much admired intellectually by Professor Blunt and worked at the Courtauld Institute on 17th-century French painting. If one reads it inquisitively, A History of the World in 100 Objects assumes the role of a sort of Bible Moralisée.

I suggest that MacGregor tells you, between the lines, a great deal about himself and his view of the world. From the British Museum collection I learnt much about unfamiliar objects. I greatly enjoyed MacGregor as my guide and companion, and indeed I found his book highly intelligent, delightfully written and utterly absorbing.

Comments