Long in the writing, deep in research, heavy to hold, this is the latest of umpteen biographies of Vincent van Gogh (1853-90). But it should be said straightaway that it is extremely readable, contains new material and is freshly, even startlingly re-interpretative of a life whose bare bones are very familiar. The more one reads, the more absorbing it becomes, both in its breadth of approach and its colossal detail.

Potential readers, however, should be warned: this is no sentimentalising study, no apologia for the excesses of the ‘mad genius’ of popular renown. Quite the contrary: one’s dismay intensifies as the self-crucifixion of Van Gogh’s life unfolds, disaster after disaster on page after page.

In the 1870s and early 1880s his art dealing, teaching, evangelical preaching, attendance at art schools all ended in frustration and failure. Although devoted to the idea of family life, his presence in his father’s presbytery was often explosive; his attempts at wooing led to rejection; and the famous relationship with his brother Theo was riddled with difficulties, deceptions and misunderstanding: Vincent’s ideal of fraternal love was pitched far too high above reality. He bullied and emotionally blackmailed; he quarrelled with friends and contacts willing to help him. There was never any compromise. And it was this last, of course, that led to his inviolable achievements as one of the great painters of the 19th century.

It is sometimes forgotten that although Van Gogh was born into the modest circumstances of a pastor in the Dutch Reformed Church, his family was well known, and included rich relations and art-world connections. His uncle was a partner in Goupil & Co., the highly successful art dealing firm in The Hague. At 16, Vincent was apprenticed there and then transferred to Goupil’s London branch. It was here that he gained his phenomenal knowledge of the English black-and-white illustrators whose work he loved (as well as his passion for Dickens and George Eliot).

A stint in the Paris Goupil ended in his dismissal, partly owing to his increasing religious fanaticism and abrupt rudeness to customers. He went to teach in a near-Dotheboys school in Ramsgate; became an assistant to a Methodist minister in Isleworth; attempted instruction towards ordination in Amsterdam and, impatiently abandoning this, took himself off as a missionary to the Borinage mining district of Belgium.

Here, in a landscape of Zola-esque horror, his folie religieuse led to a nadir of self-abasement and neglect. Once more he was dismissed, and his father seriously considered committing him to an asylum. But in the following year, 1880, his early interest in drawing and knowledge of the contemporary art world saw him ‘find his work’. His desire to live a life motivated by Christian precepts was exchanged for a fierce espousal of art and an equally fierce rejection of bourgeois values and morality.

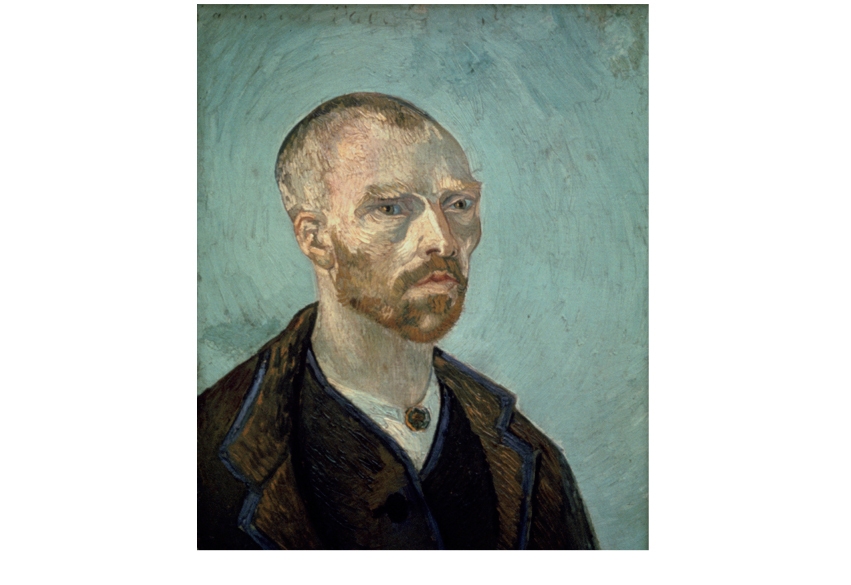

Drawing became his passion. His slow but sure mastery of line remained the under-pinning of even the most spontaneous and blazing paintings of his later years in the south of France. In 1886, until then more or less living off his brother, he went to join Theo in Paris and came to know the work of the Impressionists at first hand. The transformation in his painting was tremendous — in his handling of paint, heightened colour and new subject-matter. His ideas on what art might express were overhauled, the morality of his aesthetics finally replacing his long-lost religious faith. In 1888 he abruptly left for Arles. He had just two years to live, but it is to this period that his masterpieces belong — the sunflowers, the bedroom, the chair, the postman, the boats on the beach, his ‘Yellow House’ under a cobalt blue sky.

Around the middle of this book, the authors appear to lose sympathy for Van Gogh: so too might the reader. He is often appalling in his demands, a wheedling neediness alternating with contemptuous anger, his famous letters to Theo often found to be deceptive when checked against the facts. But as we approach the end, sympathy returns. After the disastrous visit to Arles by Gauguin (who the authors cordially dislike), ending in the incident of the ear, and a local petition to have the mad Dutchman removed from his house, Van Gogh suffered several severe breakdowns (diagnosed as nonconvulsive epilepsy) while incarcerated in the asylum at Saint-Rémy. He nevertheless managed to paint a further group of astonishing works, including ‘Starry Night’. In 1890 he came north, and at the end of July committed suicide.

But did he? The authors scrupulously examine the evidence, particularly an old rumour that local youths were responsible for the fatal gunshot. They leave an open verdict, but seem to favour accident over intent. We shall never know; but of one thing we can be sure, as this book grimly tells us, Van Gogh, in a sense, had been committing suicide for much of his life, a victim of his extreme humanity.

Comments