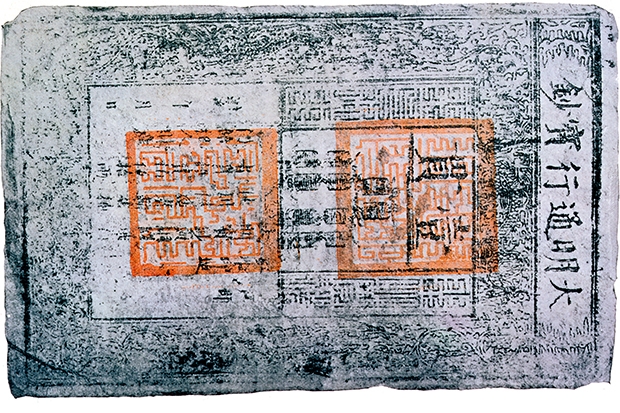

Kublai Khan, said Marco Polo, had ‘a more extensive command of treasure than any other sovereign in the universe’. There were no jangling pockets of coins in Kanbalu. Bark had been stripped from the mulberry trees and beaten into paper notes. The notes carried delicate little pictures of earlier currency — long, frayed ropes weighed down with coins. It was as though they were mocking the old ways.

Paper money had been produced in China from as early as the 7th century, but that did not stop Marco Polo from gushing that the Great Khan had discovered ‘the secret of the alchemists’. Back home, there was much curiosity but apparently little urgency. Only in 1661 did the first banknotes circulate in Europe. Sweden led the way, printing white, countersigned ‘Palmstrucher’ notes at the Bank of Stockholm. The goldsmiths of London issued their own ‘running cash notes’, while the Bank of England began to print notes ‘payable to bearer’ soon after it opened its doors in 1694.

It feels strange to be waving goodbye to all this, to the crunchy, wrinkled, eminently palpable paper banknote and its history. The new fiver, which enters circulation next week, is made from polymer, an altogether less romantic material than cotton paper. The polymer fiver will be followed by a polymer ten-pound note next summer and a polymer twenty by 2020. And so the Age of Paper dies.

The new notes are said to be cleaner, safer and stronger than the old ones. The fiver is certainly brighter. It also has the remarkable quality of being both slippery and clingy at once. The Australians have been using polymer for their notes since 1992, since the heat caused their paper ones to deteriorate rapidly, and so far it has aged well. The new UK fiver shows off what the plasticky material can do. It has holograms and a clear window with Big Ben running through it, gold on one side, silver on the other. Everything you could possibly want from a macromolecule. Polymer notes also have the advantages of being washproof and exceedingly difficult to counterfeit. Only 0.0075 per cent of UK banknotes were found to be fraudulent last year, but it’s clear that forgery continues to be a concern.

‘One thing the Bank of England is really keen to get people to do is to look at their banknotes,’ says Jennifer Adam, curator of the Bank of England Museum, where a new Banknote Gallery is opening this week to mark the arrival of polymer. ‘Know your banknotes, understand the images and the feel and the security features so you can be assured that what you’re getting is the real thing.’

So many of the historic notes in the gallery are stamped ‘FORGED’ that you can forgive the Bank for being cautious. Forgery became so widespread in the late 18th and early 19th centuries that small-denomination banknotes had to be withdrawn from circulation altogether. Writing in Household Words, the magazine he edited in the 1850s, Charles Dickens set the ‘standard epoch in the annals of Bank Note Forgery’ at 1797, four years after the introduction of the first-ever five-pound note. In the middle of the French revolutionary wars, the British began hoarding their coins, which led to a shortage in circulation. In place of bullion, the Bank of England issued £1 and £2 notes, but so rapidly and in such quantities that their quality declined. Many people were too poor ever to have seen a banknote. The counterfeiters seized their opportunity.

They must have heard, though, of poor old Richard William Vaughan, the Oxford-educated clerk who had had some banknotes forged a few decades earlier and given them to his fiancée for safekeeping. She observed that they looked a little thicker than usual, but he told her that not all banknotes were the same. Weeks before the wedding, the forgery was reported and Vaughan arrested; the notes were yet even to enter circulation. Stuffing a note into his mouth, Vaughan attempted to eat the evidence, but enough remained for him to be convicted at the Old Bailey. In 1758, he was executed at Tyburn.

A line of hanging bodies, a noose, and a sea of ships destined for Australia fill a grim cartoon by ‘the modern Hogarth’, George Cruikshank, from 1819. More than 300 people were executed for forging banknotes between 1797 and 1817 alone, and many more exiled for possession. Bank forgery remained a capital offence until 1832.

It’s disgraceful to think how little all that brutality achieved. The threat of the gallows did little to deter forgers, who ‘snapped their fingers at the executioner, and went on enjoying their beefsteaks and porter; their winter treats to the play; their summer excursions to the suburban tea-gardens; their fashionable lounges at Tunbridge Wells, Bath, Margate, and Ramsgate…’, as Dickens (whose novels were surely the best corrective to criminality) observed in 1850. It was far better, Dickens suggested, to improve the banknote ‘as a work of art’. He was right. The art of the modern banknote is now quite indistinguishable from its security features.

It was Dickens’s friend and illustrator Daniel Maclise who provided one of the most enduring pieces of banknote art. In 1855, the year of the first ‘white fiver’, he made a study of Britannia, the Bank of England’s emblem. Considering the Bank had recently achieved a monopoly on the issue of banknotes, she really ought to have looked all the steelier. Maclise, however, rendered her a merciful maid. She continued to grace banknotes until the white fiver was replaced with a colour note in 1957. On the groovy, Spirograph-like notes that followed in the 1960s — the first to feature a portrait of our Queen — Maclise’s Britannia finally made way for a younger model. This time, she looked something closer to Bathsheba. ‘More like a bathing beauty,’ said one critic.

Our new fiver, with its striking picture of Parliament over Churchill’s right shoulder, takes us back not to the 1960s, but to the 1970s. That was the decade the artist Harry Eccleston introduced the sharpest historical and architectural designs to the modern banknote. A vibrant blue-green scene of William Shakespeare’s stage, Romeo and Juliet playing upon it; Sir Issac Newton beneath the apple blossom; and one that’s pleasantly familiar, the exquisite £50 note featuring Sir Christopher Wren with St Paul’s, the City sprawled out beneath the stars while the Phoenix rises from the ashes of the Great Fire of London.

I ask at the Bank of England whether it might be worth hanging on to my last paper fiver before the Age of Polymer begins. ‘Unless it’s absolutely crisp, uncirculated, untouched, it’s unlikely to increase in value as these things are mass-produced,’ the curator says. ‘But I tend to find that, if you discover something you used in childhood but don’t any longer, it’s an instant trip down memory lane.’

Comments