Geoff Dyer is the least categorisable of writers. Give him a genre and he’ll bend it; pigeonhole him and he’ll break out. Clever, funny, an intellectual with a resolutely bloke-ish stance; irreverent and incorrigibly subversive, this is the man who set off to write a study of D. H. Lawrence and came up with Out of Sheer Rage, a rant against academia in which Lawrence figured as a spear-carrier. His book about jazz, But Beautiful, started life as a critical study, and in its final form combined laconic history with poignant vignettes; short stories that uncovered the heart and soul of the music. Fiction as truth.

His most beguiling book, Yoga for People Who Can’t Be Bothered to Do It, was a collection of anti-travel articles and mood pieces, with some hair-raising, first-hand drug-taking stuff, and an essay on Leptis Magna that managed to be simultaneously insightful, thought-provoking and hilarious.

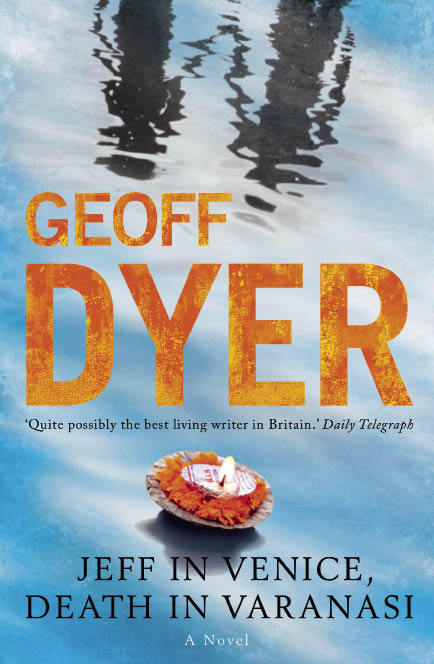

Dyer is more than a cult writer; he’s a virus, invading your system. You look at things differently, embracing the idiosyncratic, keeping the obvious at bay. Jeff in Venice, Death in Varanasi is his latest oddity. So where does it figure in the Dyerarchy? Described as a novel, it is in fact two novellas, set in two cities, linked only (unless I’m missing something) by the fact that the central figure is a journalist in town to write a commissioned piece. Dyer himself has called it a diptych.

Jeff in Venice begins with Jeff Atman setting out to cover the Biennale for a magazine called Kulchur. He is forty-something, tall, thin, consumed with anxieties about everything: status, job, mortality, party invitations … Worried about going grey, he asks if the hairdresser can dye his hair.

‘Yes’ he said, ‘Dyeing is an art like everything else. We do it exceptionally well.’

A hairdresser who quotes Sylvia Plath is the man for Jeff. With his newly brown thatch he takes his Ryanair flight into artworld madness, and the Biennale springs to gaudy, freeloading life — the Bellini worshipped here not the painter but the alcoholic mix. He also meets the woman of his dreams, and the book changes gear: resonances mount up: like Aschenbach, Jeff is gripped by erotic fever, and fleeting glimpses of Mann’s text surface through the pages. Atman in Sanskrit means ‘Self’, though Dyer does not tell us so. This name game recalls Amis’s Money which featured not only a John ‘Self’, but a ‘Martin Amis’. The beautiful and mysterious woman Jeff meets at a party is called Laura. Echoes of Petrarch? Certainly Jeff yearns for Laura, but luckier than Petrarch, possesses her — several times. Their explicitly rendered inventiveness could well leave some readers feeling sexually underprivileged.

Laura, witty and confident as Dyer’s women usually are, is an ambiguous figure and ultimately bad news, re-introducing Jeff to cocaine, upending his life. Once the sex takes over, the fun seeps away; the carousel slows down. By the end I felt we had explored orifices — including nasal passages damaged by coke-snorting — for long enough. The first 93 pages are vintage Dyer, painfully funny, slyly observant, brilliant, full of wild misery. After Laura’s departure, nightmares and a sense of doom creep in.

Death in Varanasi also begins with a journalist setting off to write an article — this time an unnamed first person narrator (Jeff, perhaps?), the destination another watery city: Varanasi, with its temples and burning ghats. The narrator experiences India in all the usual visitor ways: heat, traffic, beggars, filth and diarrhoea, its terrible beauty, the ubiquity and multiplicity of Hindu gods. He makes some friends, yearns half-heartedly after a woman or two, smokes some powerful bhang and gets seriously stoned. Gradually he unravels. There are hints that, as in Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Venice is everywhere. The mystic fog thickens, and by the end our narrator is adrift, like the kites over the funeral pyres. You can almost see the T-shirt: ‘I went to India and lost my Self.’ Alas, he has also pretty much lost his sense of humour, though black comedy surfaces intermittently. There is a vivid sense of place; Varanasi crumbles colourfully into its waterfront. But description is something other writers can do. From Jeff Dyer we want more.

Comments