What might a bright working-class boy from south London have learnt in his school history lessons a hundred years ago? We know something of his curriculum from notes made by the poet and painter David Jones about his own Edwardian education – paternalist, imperialist, chauvinist – at Brockley Road School, a state-funded secondary from 1906-1909.

Summing up the ethos of his school history lessons he made this list:

Below the belt / Natives / Sportsman / Whiteman / Boxing / Lower Deck / Club / English woman-hood / Dr Livingstone / North West Passage / ‘but not the six hundred’ / Stock exchange / Slave trade / …sun never sets / Royal Naval & Military Tournament / Clean Living / Cricket / Gordon / Kitchener / Florence Nightingale / Nelson / Lucknow / Beef Eater / Virgin Queen / Fine body of men

You wouldn’t get away with that today. All the blokey sport would have to go. You certainly wouldn’t teach how the white man kept the natives in check. Nor set coursework on Florence Nightingale, without hailing the efforts of Mary Seacole. And we can’t have a fine body of men riding into battle to protect the flower of English woman-hood.

I’ve been thinking about this list after visiting two beguiling and richly illuminating new exhibitions of Jones’s paintings and inscriptions at the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester and the Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft in East Sussex.

Jones was born to a modest family, his father was a printer’s overseer, but the education at his school in suburban south London shared its heroes – Admiral Nelson, Lord George Gordon, Earl Kitchener – and its battles – Lucknow, Balaclava, Trafalgar – with the history lessons taught at Eton and Harrow. History was the deeds of great men – with the honourable exceptions of Boadicea and Bess – most of them white and aristocratic.

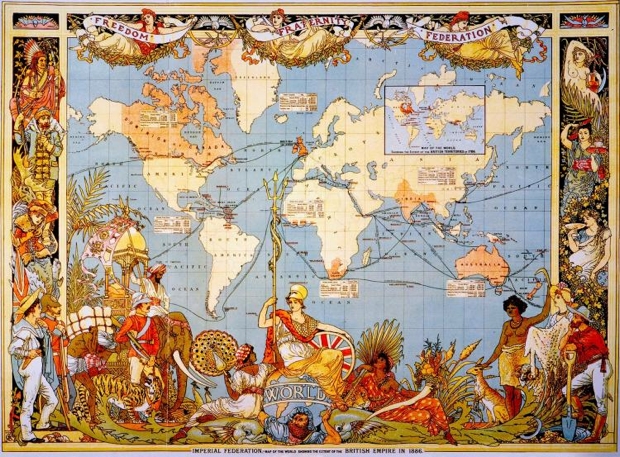

While I wouldn’t entirely advocate a return to this sort of ‘sun never sets on the British empire’ history teaching, I do envy Jones his grand sweep of historical knowledge. His education began with the Roman invasion of Britain and proceeded up to the Edwardian day via Agincourt, the Elizabethans, the English Civil War, the Four Georges, and the Victorians.

At my London girls’ school in the early noughties, on the other hand, we did three isolated periods: life in a medieval castle, the Stuarts and the trenches. I had no clue of how history fitted together and gave up the subject at the earliest opportunity.

It was only when I went up to university that I grasped any wider history. The weekend before I was due to start a degree in history of art and in a panic about having no historical framework on which to hang my paintings, I read Ernst Gombrich’s A Little History of the World.

It was a revelation. Here it all was, in the order it had happened, told like the most gripping of bedtime stories. ‘All stories begin with “Once upon a time”’, Gombrich writes. ‘And that’s just what this story is all about: what happened, once upon a time.’

Michael Fordham, a history teacher at the West London Free School who gives his pupils Gombrich’s chapters on the French Revolution, has fought against the ‘Yo! Sushi’ approach to history where ‘you pick a few bits off a conveyor belt and hope they fit together’. He is adamant that ‘to begin to ask more important questions you have to understand the chronology first.’

I regret my own Yo! Sushi history education. I rather wish I might have had – and hope today’s post-Michael-Gove pupils increasingly do have – something between David Jones’s ‘Fine body of men’ and Professor Gombrich’s ‘Once upon a time…’

Comments