Philip Hensher has narrated this article for you to listen to.

It might help if we stopped calling them ‘the Brothers Grimm’, which always makes them sound like characters in one of their fairy tales. We don’t talk about ‘the Sisters Brontë’, after all. In reality, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm have been described, very accurately, as ‘visionary drudges’. The Children’s and Household Tales, the first edition of which was published in 1812, was only a part of their grand project to establish a German cultural and linguistic identity. The brothers were primarily philologists, concerned with the meaning and history of words, and their investigation of German folk culture, narratives, myths and legends was rooted in an austere examination of language.

Household Tales came at the beginning of long careers, and were followed by much more rigorous projects. A study of German legends and an extremely taxing and thorough work on German mythology followed. One might guess that when George Eliot makes it clear in Middlemarch that Mr Casaubon can’t write The Key to All Mythologies because he is ignorant of German, she has Jacob Grimm’s 1835 German Mythologies in mind.

Jacob’s linguistic works include a History of the German Language and a remarkable German Grammar, which would on its own have preserved his name. He would have preferred it to have been called Germanic Grammar, since it explores the relations between different Germanic languages, including English. Since William Jones’s lectures in Calcutta in the 1780s, scholars had been investigating the links between Indian languages such as Sanskrit and those of modern Europe. Jones’s example was the journey of the Sanskrit word duhitar (perhaps ‘one who brings the milk’) to the English word ‘daughter’. Jacob patiently mapped the morphological changes, and established ‘Grimm’s Law’ for the way sounds shift, which still holds.

Then there is the great dictionary of the German language, the Deutsches Wörterbuch (DWB). The first volumes were published in the brothers’ lifetimes, the first in 1854 – Wilhelm died in 1859, Jacob in 1863. But it wasn’t completed until 1961, by which time a unique diplomatic agreement for co-operation between West and East Germany was necessary. By contrast, the New English Dictionary (OED) was published from 1884 to 1928. The Wörterbuch aimed at scientific rigour, but there were some idiosyncrasies that had to be curbed as the project proceeded. The Grimms’ definition of Amtmann (district magistrate), for instance, mentioned ‘our blessed mother’ and that of Ablass (indulgence) took the opportunity to glorify the triumph of Protestantism.

These were lapses much more like those of Dr Johnson than James Murray. Some of the etymological speculation doesn’t remotely stand up – for example establishing a connection between the adjective arm, meaning ‘poor’, and the noun arm on the grounds that one might put a consoling arm around someone poor. There was also the eccentrically crusading decision to abolish the capitalisation of German nouns and, perhaps most tellingly, the decision to exclude most words of foreign origin, even if they were in quite common use.

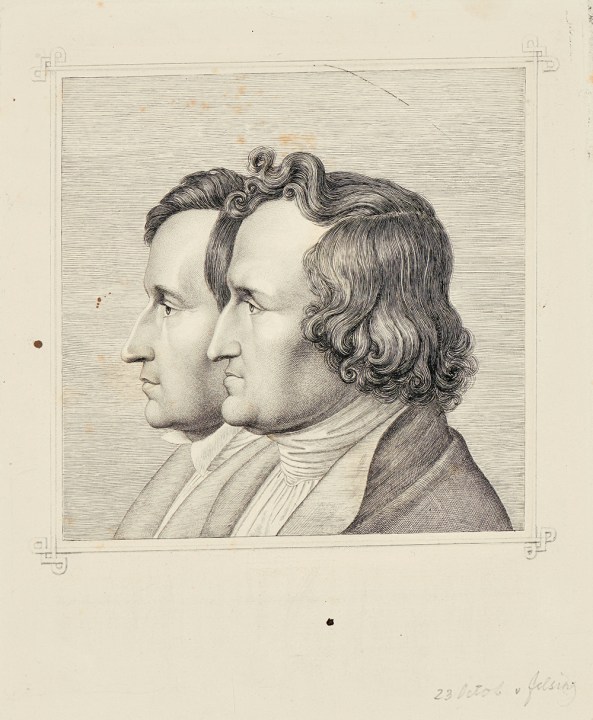

The brothers were very different: Jacob inward and rigorous, Wilhelm a cheerful family man

This decision to exclude foreign elements, as if they were tainting Germanic purity, influenced other parts of the Grimms’ work. In later editions of Household Tales, the brothers removed stories such as ‘Puss in Boots’ and ‘Bluebeard’ that had come to seem rooted in French versions. Although they maintained an interest in cross-cultural ancestries, their main concern was to establish a coherent and perhaps even exclusive body of German culture. Household Tales attempted the impossible task of interesting both scholars, who were presented with an apparatus of narratological variants, and small children who would just enjoy the stories. This was very different to the English language series of Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books (1889-1913), which reached out to a huge range of world folktales in a mild spirit of imperialist anthropology.

Household Tales actually only attained their monumental standing after the Grimms’ deaths, with the unification of Germany and the decades of nationalism which led to catastrophe. Not even Richard Wagner was so focused on the Germanic, setting two of his operas in Spain and Cornwall. In retrospect, the Grimms’ inclusion of grossly anti-Semitic stories had a sinister significance, but the emphasis on cultural purity did the worst damage.

A further point of consideration might be the Grimms’ dependence on much more educated sources than their English-language equivalents. All the contributors to the first volume of the dictionary were professors, philologists and clergymen, and Jacob discouraged contributions from unknown members of the public – very different from Murray’s wide-flung net. For the tales, the Grimms liked it to be thought that they had gathered folk stories from travelling widely and listening to simple folk. They made quite a deal out of Dorothea Viehmann, their one peasant-like source, including a picturesque biography of her and even, in one edition, her portrait. In fact, most of the stories were supplied by a small number of highly educated women of their acquaintance. They themselves were well-connected gentry, with relations in various small German courts, without a great deal of money to hand.

Still, despite reservations and conspicuous limitations, the brothers achieved a colossal amount in setting cultural and linguistic analysis on a solid footing. Unfortunately, they were largely dependent on the whims of patron-princes, which could change for no reason. The presentation of a major work to a prince might elicit the response that it was to be hoped the Grimms had not neglected their paid sinecures as court librarians. Jacob went as far as to take diplomatic posts and even attended the Congress of Vienna in an official capacity.

When a prince took umbrage, it could be disastrous. Both brothers lost their jobs at the University of Gottingen when the King of Hanover decided to intervene and sacked seven professors of liberal tendency (this was Queen Victoria’s wicked uncle the Duke of Cumberland – the thrones of Hanover and England had divided at her accession, since Hanover operated under Salic law.) The dictionary only came about because the Grimms had to move to Berlin and find some way of making a living.

Ann Schmiesing’s book is a reliable account of Jacob and Wilhelm’s careers, admirably knowledgeable about the intricate world of the princely states the pair negotiated, and the intellectual milieu of idealistic German nationalism that is now so hard to disentangle from its barbaric subsequent developments. The poet Brentano’s interest in folk poetry and the jurist Savigny’s suggestion that the innate spirit of a nation forms its laws are mined to good effect.

The brothers were, in fact, very different in temperament – Jacob much more inward and rigorous, Wilhelm a cheerful family man, whose independent work, such as his book on runes, is of less solid quality than his brother’s. Schmiesing does a good job in suggesting how their work, which they believed addressed eternal German verities, reflected the interests of the time. ‘Hansel and Gretel’ was altered so that it is a stepmother who behaves cruelly – the sources indicate a mother, but 19th-century sensibilities could not endure such a smear on the natural feelings of motherhood.

The book does betray occasional attempts at hipness, perhaps the result of years of trying to hold the attention of American undergraduates. The Grimms were ‘not project managers’; and, wanting to look at paintings in France, Jacob found that ‘gaining access to these spaces was a hassle’. But I think we can put up with that. On the whole, this is a thought-provoking discussion of the truth that the most dangerous act in the world – the thing with the most lasting and least predictable consequences – is not war or revolution. It is simply writing down the words Es war einmal…(‘Once upon a time…’ )and watching blood, revenge, gory redemption and the immensely satisfying murder of the uncivilised unfold.

Comments