When it comes to defending the free market, and making the case for fiscal sanity,

there’s scarcely anyone better than David Cameron. He was on superb form in Davos yesterday, giving much-needed blunt advice to the continentals. ‘Eurozone countries must do everything

possible to get to grips with their own debts,’ he said.

And he’s right. The snag, as I say in my Daily Telegraph

column today, is that Cameron’s definition of getting to grips with debt involves increasing it more than Labour planned to, more than France, Germany, Italy or Portugal. On the first sign of

trouble, his government gave up on its deficit reduction timetable – it will now halve the deficit over five years, whereas Darling promised to do it in four.

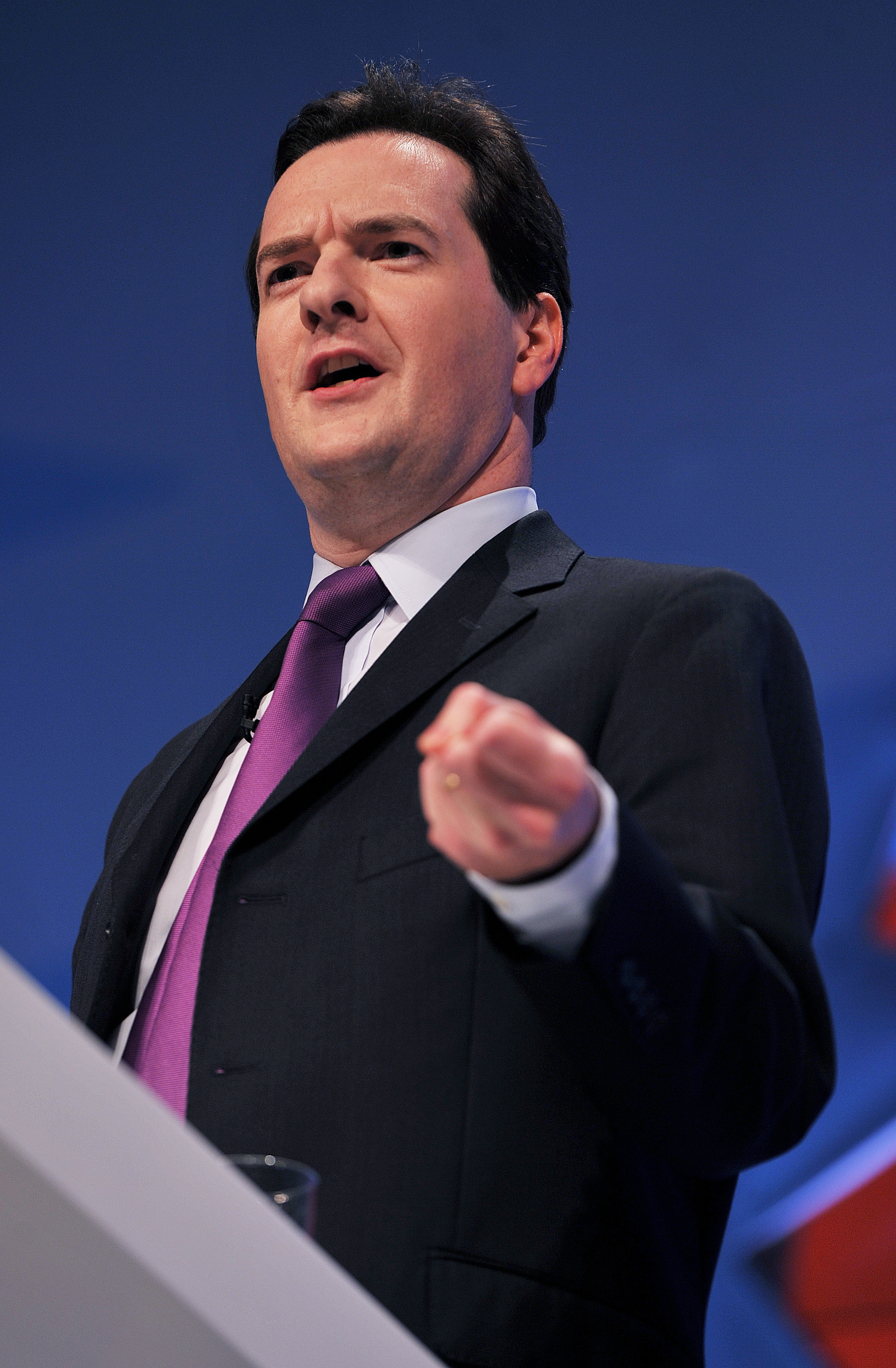

As The Sun says today, Cameron would have more credibility at Davos if the British economy was growing. Instead it has stalled, and Osborne seems to have run out of ideas to get it moving. He said his budget last year would ‘put fuel in the tank of the British economy’, but instead it’s started to flag. He has abandoned his plans to reduce the 52p tax – a massive ‘keep out’ sign plonked over Britain scaring away entrepreneurs.

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the British economy is now midway through a Japanese style ‘lost decade’ – except 2008-18 may be worse for us than any ten-year stretch was in Japan. The government’s hopes seem to be pinned on more Quantitative Easing, perhaps bringing the total up to £500 billion. That’s a truly colossal figure, and one fraught with danger. It will reduce borrowing costs, and – ergo – government debt interest bills. But this also means lower returns for pensions, resulting in bigger shortfalls in pension schemes and companies hiring less or paying less to fill that gap. There’s no such thing as free money. QE is also inflationary, and so will sting the poorest – who, as Nick Clegg rightly said yesterday, are feeling the pain.

It’s hard to say ‘Well, George is sticking to his radical deficit reduction plan’ because he isn’t. The plan he is sticking to is for mild cuts in state spending: cutting less in four

years than both Denis Healey and Barack Obama managed in one year:

Nor do I buy the rather defeatist argument that Britain lies at the mercy of the eurozone. We’re the fourth largest economy in the world, and have our own currency. If Estonia can achieve economic

growth (6.5 per cent in 2011) with imaginative policies, then Britain can too.

The Times said recently that Britain’s main problem is an imagination deficit in the Treasury. That we just can’t think of ways to grow the economy. Britain still seems trapped in a Brownite consensus, with tax cuts regarded as a reward for a decade of pain – not a stimulatory tool in themselves. In the US, each of the Republican candidates has radical tax-cutting policies – all intended as ways to boost the economy, not as bribes. In Britain, we’re debating whether to cut departmental spending by an average of 2.2 per cent a year (Brown’s plan) or 2.8 per cent (Osborne’s). The difference between these two figures purports to be the difference between left and right in Britain.

This is not a timid government, and Cameron is not a timid Prime Minister. School reform, welfare reform and police reform are all proceeding apace. But where is the economic reform? Right now, economic policy looks like the weakest link in an otherwise radical government.

Cameron’s speeches are great, and show that he understands capitalism. The Prime Ministerial spirit is willing, but the Treasury flesh seems weak. Do I believe that Osborne is smart enough to come up with a radical, pro-growth agenda at the Budget in March that will pull us out of this lost decade? Absolutely. Does he? We’ll see.

Comments