This is a strange old recovery. The News of the World has an interesting ICM poll today,

showing that 66 per cent think the economy is getting worse. It’s not: GDP is growing and we have the second-highest job creation in the G7. Rather than losing jobs to China, we’re

flogging Coventry-made Jaguars to Beijing billionaires (one of the random gems uncovered by our new Twitter feed @LocalInterest). So why is

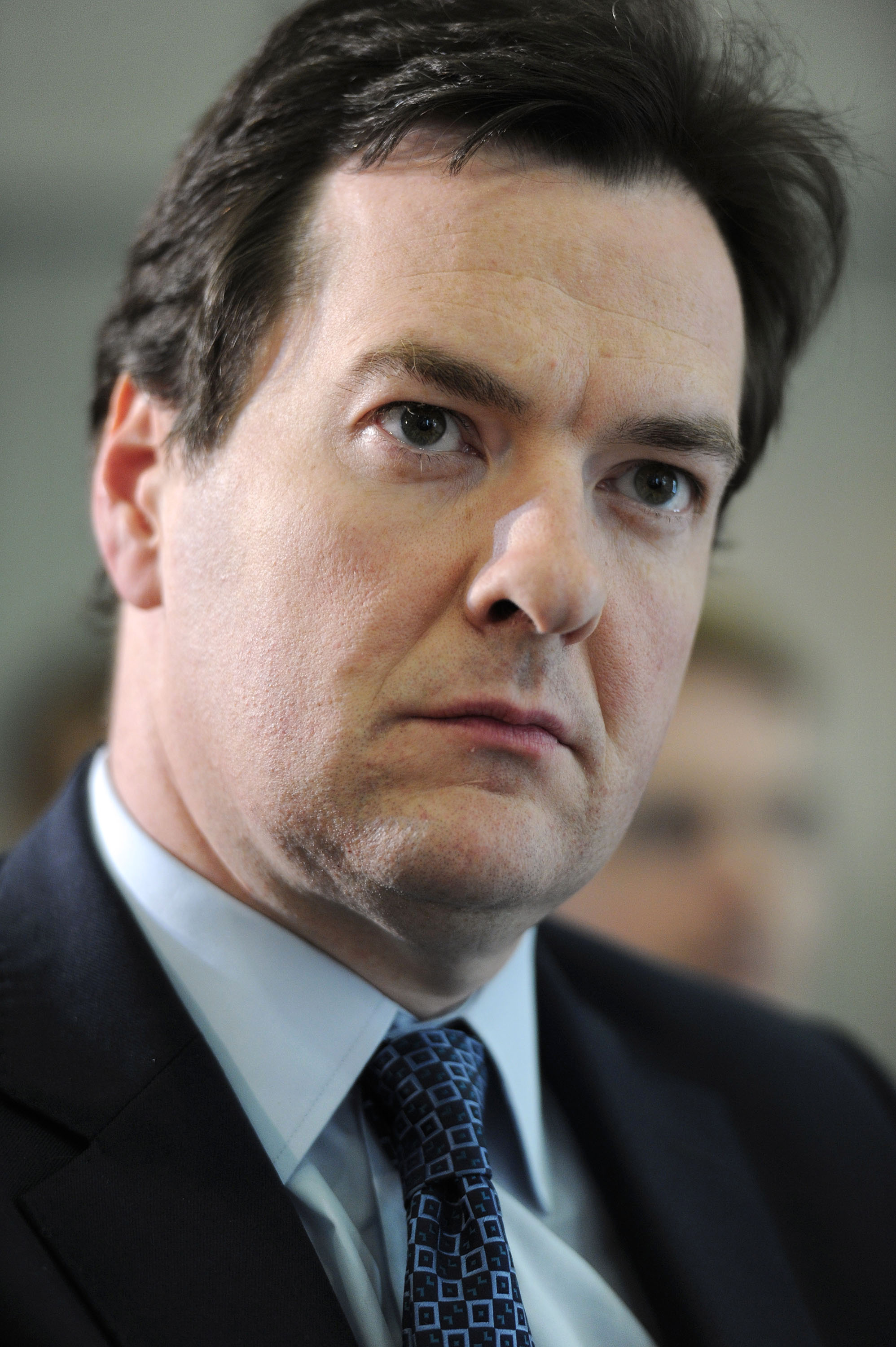

everyone so glum? And why do 52 per cent think that David Cameron and George Osborne are doing “a bad job” with the economy?

This is a strange old recovery. The News of the World has an interesting ICM poll today,

showing that 66 per cent think the economy is getting worse. It’s not: GDP is growing and we have the second-highest job creation in the G7. Rather than losing jobs to China, we’re

flogging Coventry-made Jaguars to Beijing billionaires (one of the random gems uncovered by our new Twitter feed @LocalInterest). So why is

everyone so glum? And why do 52 per cent think that David Cameron and George Osborne are doing “a bad job” with the economy?

In theory, Osborne’s recovery is coming on well. His “cuts” agenda is simply a souped-up version of Alistair Darling’s, but Osborne cuts about 1 per cent a year faster. It

suits both Labour and Tories to pretend this isn’t the case, perhaps why both are careful never to quantify the cuts. But GDP growth has returned, and a million new jobs should be added over

this parliament. Osborne is a brilliant politician, but not very interested in economic debate (his reluctance to engage has allowed Ed Balls’s “massive cuts” narrative to triumph).

And I suspect he thinks the figures will speak for themselves in the end. Employment up, economic growth back — time, then, to take a bow and win a Tory majority.

But statistics are treacherous. The politician in his wood-panelled office might believe that the recovery is coming on well, as civil servants feed him metrics on manufacturing and GDP growth and

low gilt yields. But the voter, en route to the supermarket, sees a very different set of metrics. Nappies: up 10 per cent. Butter: up 15 per cent. Tinned fish: up 20 per cent Deodorant: up 40 per

cent. And that was just last Christmas. Since then Britain has

struggled with the highest inflation in Western Europe, where salaries have been flat. The Office for Budget Responsibility, which now does Osborne’s forecasts, estimates that it will be 2013

before wages catch up with prices. As Sir Mervyn King put it, the average Briton is suffering the most sustained attack on living standards in 80 years. Perhaps the single most stunning figure in

the poll is that 38 per cent say “I can’t imagine I’ll ever have the money I want to meet my needs.” This isn’t just post-recession blues. This is despair.

So why is Osborne being seen to do a “bad job?” Perhaps because, as far as cost of living is concerned, he has become part of the problem. In jacking up VAT to 20 per cent Osborne

compounded the pain. The News of the World poll asks people to name their no.1 headache: it’s fuel prices at 136p a litre — of which 80p of is pure tax. In Britain, petrol retailing is

a joint venture between the Exchequer and the petrol retailer, the latter being a junior partner. If voters think Osborne is making things harder for them, they are right.

There is a real danger that Osborne does not fully appreciate the danger of inflation, or the misery it inflicts. He might think: I’m not going to be asked any nasty questions about this,

because Mervyn King’s lot is handling inflation. Wrong. As Chancellor, he’s in charge of “sound money” — and he’s ultimately responsible for the fact that

Britain’s inflation is twice as high as Zimbabwe’s. Our purchasing power is being decimated, and the News of the World’s poll shows that people are angry.

Next: jobs. Iain Duncan Smith was right last week: there’s no point boasting about job creation if it means that employers are sucking in workers from overseas. In the Chancellor’s

office, statistics will show that more than 2,000 jobs are being created each day. But immigration figures show 1,600 are arriving each day, and Labour Force Survey data suggests that foreign-born

workers account for most of the job increase. So the simple metric of employment is unreliable. Unless it’s shortening British dole queues, what’s the point?

Finally, debt. Osborne’s recovery will increase British economic output by £183 billion according to the OBR forecast. But net debt will rise by £400 billion. This is the drawback

to Osborne basically adopting Darling’s slow-mo plan: it still jacks up the national debt (i.e. the amount the government borrows from the public), and you’d be surprised about the

extent to which the public are aware of this. It doesn’t help create a feel-good factor.

Tomorrow, a statue of Ronald Reagan will be unveiled in London to mark what the centenary of

his birth. The Gipper won the election in 1980 by asking a simple, killer question: are you better off than you were four years ago? Osborne’s nightmare scenario is that British voters may

say “no” – that the Darling Plus deficit reduction plan he embarked upon will work, but it will be a voteless recovery.

The Tories had a voteless recovery in the mid-90s. Inflation and interest rates are at their lowest for 30 years; unemployment fell to half the European rate. But as Sir Ivor Crewe wrote at the time:

The News of the World poll shows an utter absence of a feel-good factor — due to factors that are likely to remain for some time (high inflation, flat wages, lack of anyone seeming to give a damn about either). And Osborne’s reluctance to get his hands dirty with economic arguments means that he risks not securing credit for the recovery when it arrives.“For economic recovery to translate into electoral recovery, two additional conditions are needed: first, voters must experience the recovery and expect it to continue (the feel good factor); second, they must give the government the credit.”

Osborne doesn’t need a Plan B. But I have been arguing for a Plan A+ in the form of a growth-stimulating tax-cut for the low-paid, financed by more ambitious spending cuts. This would not only help with the cost of living, but help recouple the link between the UK jobs market and the UK dole queue — and it’s a move that Osborne can claim credit for. His friend Anders Borg did this in Sweden, and said at election time: our tax cut has given you the equivalent of an extra month’s salary in a year. Result: an historic re-election.

Yes, Osborne’s recovery is going to plan. But it’s becoming increasingly clear that his plan is no longer enough.

UPDATE: Thanks to Matt Cavanagh, from the IPPR, for pointing out via Twitter that 1,600 immigrants only “settle” in Britain if they are given leave to remain — so “arrive” is a better word. I have tweaked the post accordingly.

Comments