With Die Walküre, the central themes of Barrie Kosky’s Ring cycle for the Royal Opera are starting to emerge, and one of them seems to be wood. Not trees, so much; at least not as a symbol of life. After the rapid assembly of a world from theatrical nothingness (a bare stage), Hunding’s forest hall is simply a wall of blackened planks, with no World Ash Tree in sight. Then you notice the protruding hilt of the sword Nothung: no, that is the World Ash Tree, and Hunding has recycled it into building material. We knew he was a wrong ’un, but really: this is Sycamore Gap-level wickedness.

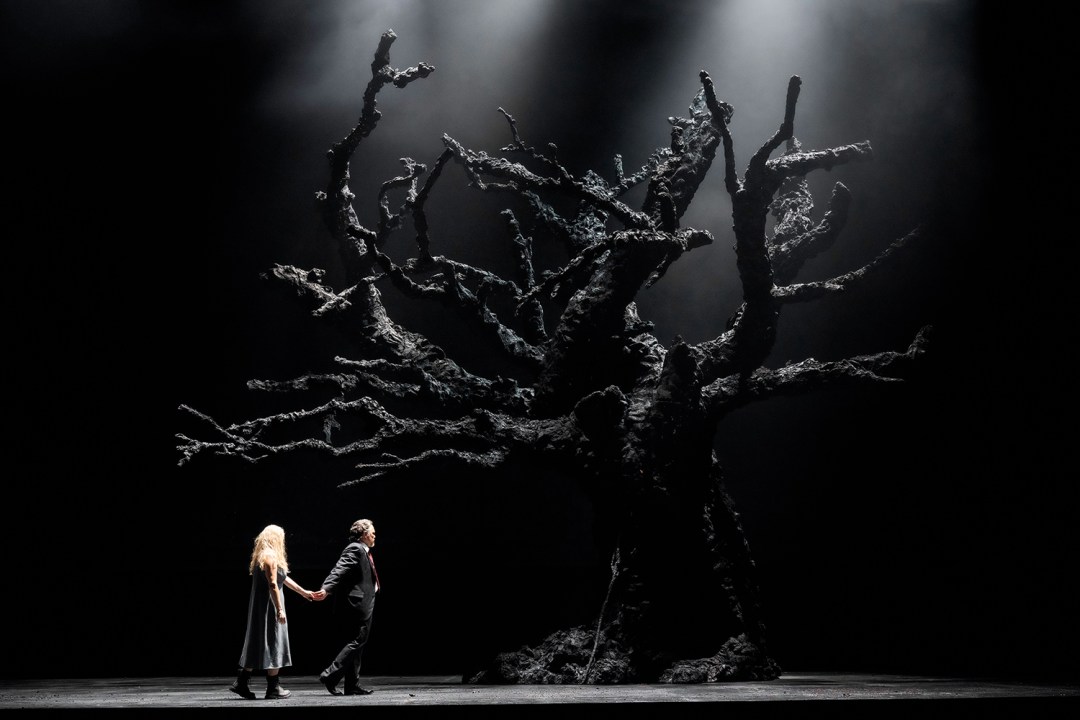

Various ex-trees recur in Rufus Didwiszus’s designs. The huge, maimed log from Das Rheingold reappears during Siegmund and Hunding’s duel, spewing blood as the betrayed hero falls and dies. The Valkyries gather not on a mountain peak but at a blasted, leafless tree beneath apocalyptic grey skies, and Wotan (Christopher Maltman) abandons Brünnhilde (Elisabet Strid) inside its hollow trunk. Branches aflame, it makes for a stupendous final image, and the surtitles even substitute ‘tree’ for ‘rock’, which is not what Wagner meant at all. Won’t the flames simply consume the tree? Ah, but it’s magic fire, remember.

Certainly, the despoliation of nature is a central theme of the Ring, and Kosky’s imagery offers a mycelium-like network of resonances and subtexts, all fructifying vigorously in the dark imaginative peat of German romanticism. The final image evokes Caspar David Friedrich’s gnarled oaks, while Hunding’s tarred wall of wood is more like Anselm Kiefer – that supremely Wagnerian poet of the forest as repository for the bloodiest and most intimate secrets of the German psyche. The Valkyries lug ashen corpses, which disintegrate on touch. The gods, meanwhile, dwell in an arid world of Berlin noir: streetlamps, fog and Eurotrash couture. Kosky has spent a lot of time working in German opera houses, and this is shaping up to be a very German Ring indeed.

After all, what could be more German than public nudity? That’s the other big recurring symbol – the naked, shuffling old Erde from Das Rheingold. She’s hard to ignore, and as the turning points of the drama approach you start to wonder how Kosky is going to shoehorn her in. She lumbers into Siegmund and Sieglinde’s love scene – a pale nude gooseberry, glumly distributing flowers. She’s wedged inside the Valkyries’ tree, and (in an admittedly shocking reveal) Siegmund pulls the sword from her bloodied, passive body.

It’s a little trite; one of those easy-win visual metaphors that allows us to pat ourselves on the back for getting the correct message. Humanity defiles nature: tick! Extra points for spotting the implication that it’s Wotan’s toxic masculinity (that phallic sword) doing the defiling. True, that’s all present in Wagner; but it’s only part of the story, and Naked Erde feels like an idea with diminishing returns, with the potential to introduce all sorts of narrative inconsistencies later in the cycle.

As for the cast, Siegmund (Stanislas de Barbeyrac) makes an affecting damaged hero and Fricka (Marina Prudenskaya) is a neon-toned queen bitch who makes mincemeat of Maltman’s frustrated, understated Wotan – a real lieder-singer’s performance, which is (mostly) a good thing. There’s cold steel in Soloman Howard’s Hunding, and Strid’s sunny, impulsive portrayal of Brünnhilde hasn’t found its centre yet. That’s alright, though, because neither has the character. Natalya Romaniw, as Sieglinde, is having a tremendous season, and she steals the show – as sensitive as a wounded animal, but capable of breaking her chains to release huge, vaulting arcs of song.

Pappano conducted, lyrically enough. The Covent Garden crowd greets everything he does with ecstasy and in this repertoire, at least, I’ve given up trying to understand why. But no Ring staging gets everything spot-on; never has, never will, never can. If you wanted a half-time scorecard for this Ring (and what else are critics for?), the urgency and scope of Kosky’s ideas – and the headlong, intensely human rawness with which he defines the characters – currently outweighs the missteps.

Still, German opera, eh? So long, so serious, so dark. Not on Georg Philipp Telemann’s watch, it isn’t, and down in the Linbury Theatre two young singers, Grisha Martirosyan and Isabella Diaz flirt, pout and trill their way through director Sophie Gilpin’s swinging Sixties updating of Telemann’s 1725 farce Pimpinone. He’s a wealthy waster, she’s Vespetta, the gold-digging maidservant who marries him, then proceeds to make his life a henpecked misery. One of those bright, cruel baroque comedies, in other words, though the cast and a bouncy little orchestra under Peggy Wu make it all seem rather sweet. But that’s Telemann for you. The score is as genial and inventive as Haydn, and the final duet – I’m not kidding – is a regular earworm. It’s all over by 9 p.m, too.

Comments