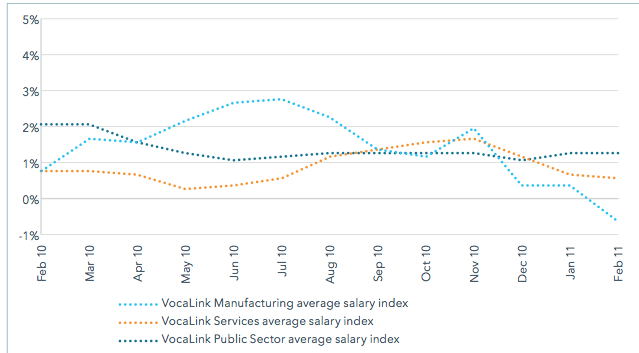

Today’s decision to leave base rates at an emergency 0.5 per cent — the lowest since the Bank of England was founded in 1694 — shows how Britain is running out of options. Not even Mervyn King would deny that Britain has an inflation problem: global prices may be up, but the UK seems to have been hit worse than almost any major economy, as I blogged yesterday. With food prices up by 6.3 per cent and CPI inflation by 4.1 per cent, what’s happening to prices? The below graph, again out today from a FTSE350 survey, suggests that pay is up by just 0.5 per cent in the private sector. And it’s even worse in the manufacturing sector.

You could argue that one should not compound this pain by jacking up debt interest. Especially as British households are the most indebted in the G7. But what’s worse: the price of debt going

up, or the price of everything going up? The relationship between base rates and inflation is not immediate, nor direct. But there is no good reason for having rates at these emergency levels when

the UK economy is back to growing at — or above — its 2 per cent trend. The below graph, also just out from the

Treasury, shows how independent forecasters expect the UK economy to grow.

And inflation? The other day, we printed Citi’s forecasts until 2012. Its forecasts run until 2016, and they don’t envisage CPI coming anywhere near the supposed 2 per cent target.

The reason that I and others advocate a base rate increase is not out of a sense of fiscal sadism. But if you lose control of monetary policy, you normally have to fix it in a horribly painful way

later on. A little pain now would save what could be, potentially, a lot of pain later — and we know what happened to a Tory Chancellor last time he had to oversee a lot of pain.

In 1997, monetary policy was nominally handed over to the Bank of England — so George Osborne has, in theory, no tools to intervene here. But the management of UK monetary policy cannot be

seen as a success. Dangerously underpriced debt created a debt bubble, which exploded in 2007. Cheap debt is — as Karl Kraus said of psychoanalysis — “the disease of which it

purports to be the cure”. Either the Bank should sort it out, or Osborne should seriously think of another way of managing Britain’s monetary policy. The future of his government may

depend on it.

Comments