quot homines, tot sententiae: as many men, so many opinions. What seemed a universal human truth for the playwright Terence in 161 BC now finds itself, amidst the chaotic swirl of online news and opinion in AD 2017, drastically in need of adaptation: quot sentias, tot sententiae – there are only as many opinions as you experience.

This should be a golden age for the exchange of opinion, for sharing diverse ideas through increasingly interconnected media. Yet, without filtering or curation, an unmanageable welter of report and comment has blurred the distinction between the two, bewildering even the most determined of readers. Strange as it is to say, the immutable importance of free speech is being lost in its curation-free expression.

Society is defended by the panoply of diverse opinion. The independent voices of politicians, the judiciary, academics, columnists and (that troubled species) experts remain its lifeblood. These fields command attention not because of idle conservatism or twee traditionalism but because in each it’s so hard-won a process to gain a voice, requiring long-term study and privileged access to new material. Such views may be vitiated by alienating jargon, unconscious bias or bet-hedging opacity but their motivating force remains studied reflection.

For most of western history, information has been filtered through controlled channels. In the ancient and medieval periods, exceptional learning was required to produce – or digest – anything in writing; in the early modern period, institutional alliances dominated the printing presses; tight-knit elite circles remained in control even with the advent of newspapers and mechanised printing. The result in every case was not an illiberal system for silencing others’ voices but a network designed to ensure informed – or at least engaged – content. Furthermore, the expense of transferring an individual’s output (verbal, musical or artistic) to a medium available in public (print, record or reproduction) guaranteed that it had passed muster in an editorial context. Readers, listeners and viewers trusted that this curated vehicle conveyed high-quality content of a representative range within a fixed physical remit. If it did not, they simply moved elsewhere.

In the echoing chasm of digital space, by contrast, the instant ability to voice opinions has not engendered lucid debate but muddied the waters impossibly. On any given subject in any given hour, too much material arises even to be glanced at, let alone read or pondered. For all its innovation, it has been a striking failure of the online community to develop any cogent organisational principles to structure the opinions and debates that run rampant online. The equal opportunity to voice opinions has prompted the apparently liberal but actually idiotic inference that every opinion equally deserves to be heard.

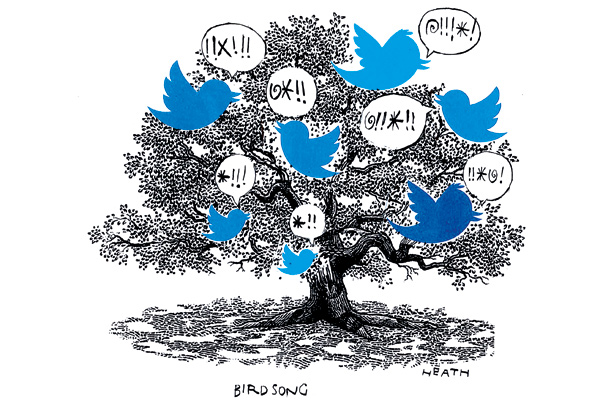

While sharp and salient points regularly appear in the comment sections ‘below the line’ on curated sites, they are too often obscured by the heavy clag of insult and outrage. Without the moorings of a specific article, opinions entrusted to the digital ether fail to fly freely. Take Twitter, a particularly abject tool for exchanging new ideas, allowing only the briefest of bleats, tweeted without context to a typically partisan audience. Not only does it fragment fact and lose the nuances of a complex world but it creates artificially closed communities: users follow only those they want to, and anyone proffering unwelcome views can be blocked permanently. In manicuring their personal microcosm, users move in ever smaller circles of reference. Yes, conversations may span the globe, but the range of views is probably narrower than those in the pub down the road.

Not only has social media unleashed gushing cataracts of increasingly black-and-white opinions, but it has bastardised news reporting. In 2016, online outlets became more popular than print and TV sources for accessing news worldwide; in the UK, twice as many people read news online than on paper, with Facebook and Twitter becoming increasingly dominant. Although both channel stories from trusted sources, the sheer scale of the networks means stories must be automatically aggregated by crude data of keywords searched. If a clickbait story lures many readers, it’s catapulted into news feeds, regardless of its truth content. In this grim feedback loop, ‘fake news’ has become a notorious – or at least newly apparent – problem precisely because curatorship has disappeared. Even the unfailingly rose-tinted helmsman of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, recently felt prompted to issue a 6,000-word letter to his ‘community’, in which he acknowledged the site’s hand in hosting rogue news and unduly polarising opinion.

Faced with this welter of (dis)information, without the steer of edited sites, an individual must piece together news and opinion organically and subjectively. This requires active searching – asking the same questions or following the same individuals – or passive consumption of the chaotic torrents of viral bluster. But when all news and opinion is self-curated, the possibility of views being challenged and changed tends towards zero. The result is both an artificially monolithic set of dogmas and intensified intolerance of anyone or anything that clashes with it.

Even apps that beam national newspapers to handheld devices are not immune from this blinkering. They increasingly allow bespoke pruning of the homepage and the restriction of stories to those you want to see. Catalysed by confirmation bias, circumscribed readers only reinforce their current prejudices and beliefs. Self-curation is no method for testing out opinions or discovering the unknown. Consider the difference between an open-stack library, where browsing the shelves in person allows serendipitous encounters with new and potentially transformative material, and its closed-stack counterpart, where the only things read are those one already knows to call up.

Far from closing down options, curated content opens up fresh vistas. Of course, if faith must be put in edited outlets as guardians of opinion, we must ask who watches the watchmen. Yes, close scrutiny of who plays the curatorial role of editor is essential – but this is nothing new. Without complaint or second thought we delegate much of our lives to curators, trusting that they guarantee value and breadth: producers, publishers, record labels, retailers, museums – even, in theory, politicians – are delegated to channel from any source whatever is worthy of closer consideration.

The same should be true in the broader world of higher education, where faith is put in wide-ranging and hard-fought syllabuses curated over generations. By definition, new arguments and diverse opinions should be challenging and uncomfortable. The more informed and more educated an audience is, the more it should be confronted. It’s an embarrassment that some universities have supported No Platforming, or have sought to ban certain newspapers. Ideas and opinions, however controversial and distasteful, are to be shredded in debate, not shrouded in the dark. I can vouch that a Cambridge interview or supervision is far less about testing knowledge than seeing how potential students can cope in the shifting sands of debate, when new information opposes established positions. My own subject, the Classics, has more than enough material to stress-test or destabilise our contemporary shibboleths – and so it should.

This is not a prompt for shrill panic but a reminder of the pitfalls that exist when curation is culled. It is heartening that print media maintains a substantial hold: The Spectator and Private Eye are enjoying their largest print circulations ever. Meanwhile, Twitter growth has slowed dramatically and Facebook News is back under human oversight after its algorithmic infelicities. But news and opinion continue to drift into contexts manifestly unsuited to handling them. To understand the value of order amidst chaos, this paradox needs reflection: opinions are richer and more reflective of personal choice when informed by those chosen and channelled by others.

Comments