The House of Lords is very old, but not quite continuous. In 1649, shortly after the execution of King Charles I, the Cromwellian House of Commons passed an act which said:

The Commons of England assembled in parliament, finding by too long experience, that the House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the People of England… have thought fit to Ordain and Enact… That from henceforth the House of Lords in parliament, shall be and is hereby wholly abolished and taken away.

This measure was nullified, however, by the Restoration in 1660. The parliaments of King Charles II, and all parliaments since, have included the House of Lords. The hereditaries served their country loyally: 59 were killed in the two world wars, as were 316 of their sons. It is in the Lords that the throne sits. From that throne, the monarch delivers his or her speech which opens each session of parliament.

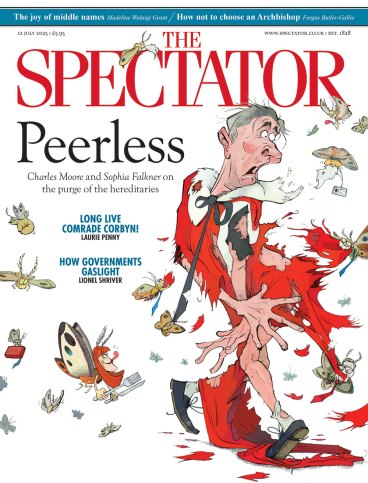

With their existence questioned, they show, despite their titles, little sense of entitlement

Now we are in the reign of King Charles III. As I write, Labour is abolishing all traditional membership of the House of Lords – except, which is interesting, the Lords Spiritual, the bench of Anglican bishops. All hereditary peers might even be out as early as the end of this month.

Why is this happening? In 1999, the Blair government abandoned its promise to reform the Lords root and branch, but was still determined to get rid of the hereditaries. Because its other reform proposals had fallen away, it struck a deal with the Conservatives: 92 hereditaries, ‘exempted’ from the cull of 700 or so, could stay until such time as a full reform package should be presented. More than a quarter of a century later, no package has appeared.

That 1999 deal is now being broken. Sir Keir Starmer is making no new active reform proposals, but he wants the ‘92’ (now eroded to 86 by the suspension of replacement by-elections) out. Lacking a New Model Army to enforce his wishes, he is not proposing to abolish the Lords outright but, Cromwell-lite, is determined to drain from it what has been its lifeblood for 800 years.

He wants every last drop. Last week, Lord Roberts of Belgravia (better known to Spectator readers as the historian Andrew Roberts) moved an amendment, which I seconded, to the bill. As life peers, Andrew and I feel we should stick up for our hereditary comrades, most of whom shy away from self-justification and prepare to go with silent, pale-faced dignity to the scaffold.

Always, until now, the monarch has had two hereditary peers in the Lords specifically present to look after the interests of the Crown – the Earl Marshal and Lord Great Chamberlain. We argued that their roles would be hampered, and the monarch therefore discourteously served, if they could no longer sit there. After all, the core doctrine of our constitution is that of ‘The Crown-in-parliament’. Why should the Crown’s main representatives be blocked from parliament’s proceedings and reduced to the ranks of the ‘lanyard classes’?

The government’s attitude echoes that of King Lear’s ungrateful daughters, Goneril and Regan, to the former monarch’s 100 knights. ‘What need you five and twenty, ten, or five?’ asks Goneril. ‘What need one?’ adds Regan grimly. So, despite our protests, out go the Earl Marshal and the Lord Great Chamberlain.

Luckily, our present King remains firmly on the throne and shows no Lear-like desire to give everything away, but the impulse which throws out peers because of their heredity logically extends to monarchs. Presumably that is why, in the days when Sir Keir allowed himself to express his own opinions unguardedly in public, he was in favour of abolishing the monarchy.

The government does not enjoy defending this legislation. It prefers sullen silence. But to the extent that it does speak, its view is that hereditary peers ‘are indefensible in the 21st century’. That is an assertion, not an argument, very like that 1649 claim that the House of Lords is ‘useless and dangerous to the People of England’.

The battle is not quite over. Last week, 280 of us defeated the government with an amendment which would allow the hereditary element to perish by the passage of time rather than sudden expulsion. There may also be deals in which a few hereditaries get life peerages instead. (I vote for keeping 25 per cent of the Labour ones, in other words, Viscount Stansgate, the hereditary beneficiary of his anti-hereditary father, Tony Benn.) But there can be no doubt that the hereditary principle in parliament is dead, killed by the convention that the Lords does not block commitments made in the winning party’s election manifesto.

What is being gained? Well, the loss of the 86 will create a bit more room in what is widely thought to be an overcrowded House. It will also remove what some see as the unfair numerical advantage of the Conservatives and improve the sex and ethnic balance (since all the hereditaries are white men). I really cannot think of anything else.

What is being lost? First, a group of people who are disinterested, in the proper sense of that word. None is there for the power or the money (both of which are very small). Unlike under the unreformed, full hereditary system, none is there as of right alone. Since 1999, hereditaries wishing to sit in the Lords must be elected by their peers, some chosen by the whole House. They therefore have to want to do something. They take junior government or shadow posts, are deputy lord speakers, chair committees. The Earl of Kinnoul, the convenor of the entirely independent crossbenchers, more than 30 of whom are hereditaries, is a hereditary peer. Lacking worldly ambition or partisan passions, knowing that their existence is questioned, the hereditaries show, despite their titles, little sense of entitlement. They are polite and benign.

We shall miss them – such characters as Earl Howe, who has sat 40 years in the House and served 15 years as a minister, or the youngish 19th Earl of Devon, a recent arrival who has held us spellbound with his well-developed and no doubt accurate claim that the Earls of Devon, who have been around since the Norman Conquest, have done more for Devon than anyone else. (Elsewhere in the magazine, Sophia Falkner – who knows a thing or two about the hereditary principle – looks at some of the others we will lose from the Upper Chamber.

More than four-fifths of the 86 men have a background from the private sector or the professions – farming, business, the law, the army; one is a vet – and therefore possess, in the current cant phrase, ‘lived experience’ of areas of national life almost unknown in the corridors of power. None has passed his life under the protection of that 21st-century iteration of the Establishment, the Blob. All have done the state some service, yet now they are to be collectively attainted.

It is sad. Part of the sadness has been peers voting to eject fellow peers – an uncomfortable thing, especially as they are being thrown out for no reason other than what opponents of the hereditary principle call ‘accident of birth’. Even in the age of mass immigration, most of us are British citizens by ‘accident of birth’. Is that such a bad principle?

They are being thrown out for what opponents of the hereditary principle call ‘accident of birth’

What is lost, though, goes beyond this temporary, dislocating unhappiness. It concerns what’s left and what might happen next. It sets a constitutional precedent which the original provision of the 92 was intended to counter. In almost any free country, it would be unconstitutional for the executive to decide to remove a portion of those who sit in one of its legislative chambers, especially if such removal increases the executive’s power. That sort of thing gets a country arraigned before the European Court of Human Rights. Such change should be made only as part of much wider constitutional reform, arrived at through broad consensus and/or a referendum. Occasionally, Labour drops little hints that something big might happen, but the evidence of its actions suggests it won’t.

Even if it did, consensus is unlikely, because people cannot agree whether they want to keep a strong House of Commons or, by creating an elected second chamber, challenge the Commons’s power. Get that wrong and you could be laying the ground for the sort of power struggle which this country last saw in the 1640s.

So the most likely thing which will happen is nothing much, at first. Except for the poor dear bishops, whose own appointments are now almost wholly in the hands of a separate bureaucracy, the Lords will be almost entirely composed of those appointed by prime ministerial prerogative. They (we – I am one of them) will continue to have some independence, because we cannot easily be ejected. But the idea that our legitimacy will be enhanced without the presence of the hereditaries is absurd. Party animosities will grow. Our fig leaf of traditional respectability will have been removed.

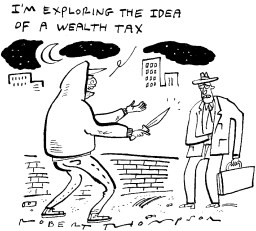

Ah, say some reformers, the answer is to take the power of patronage away from 10 Downing Street. Let an ‘independent body’ – a greatly glorified version of the ineffective House of Lords Appointments Commission – decide who should become a peer. Then the process would have ‘integrity’.

It should surely be obvious that such a system would replicate all the features of 21st-century unanswerable, bureaucratic, self-perpetuating public-sector Blobbery that have become so disliked and feared. The Lords would soon become, in those original 17th-century words, ‘useless and dangerous to the people of England’.

Comments