In an upstairs room in an unfrequented corner of Zurich’s Kunsthaus, there is a portrait of one of the unsung heroes of modern art.

In an upstairs room in an unfrequented corner of Zurich’s Kunsthaus, there is a portrait of one of the unsung heroes of modern art. Wilhelm Wartmann was the first director of this splendid gallery, and in the autumn of 1932 he mounted the first major retrospective of the work of Pablo Picasso. This autumn, to celebrate its centenary, the Kunsthaus is mounting the same show. It’s a unique chance to see how the world saw Picasso at his peak — and how Picasso saw Picasso — for this groundbreaking exhibition was curated by the artist himself.

Nowadays it’s not unusual for big galleries to devote entire shows to living artists — or for the artists themselves to roll up their sleeves and muck in. In 1932, however, this sort of thing was regarded as terribly avant-garde. British museums didn’t buy or show contemporary art and New York’s Museum of Modern Art wouldn’t stoop to stage a show curated by a mere painter. Fortunately, Herr Wartmann wasn’t so stuffy or insecure. Since the mid-1920s he’d been trying to bring Picasso to the Kunsthaus, and when Picasso put on a solo show in a private gallery in Paris (in a bid to outdo Matisse, who’d staged a one-man show there the year before) Wartmann wasted no time in inviting him to curate his own retrospective in Zurich. The show ran from 11 September to 30 October 1932.

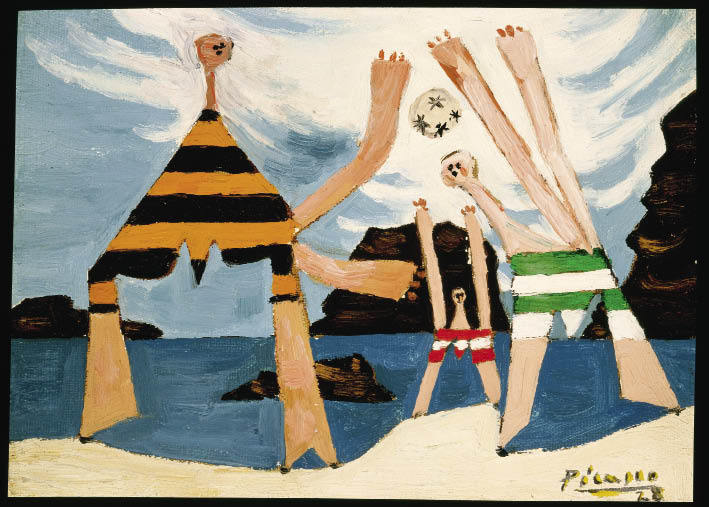

Picasso chose 225 works for this landmark exhibition, ranging from his late teens to his early fifties. It was an eclectic mix. There were pictures from his Blue and Pink periods and his Classical and Cubist phases, culminating in that subtle blend of figuration and abstraction which came to define his mature work. The critics complained that this show had been hung in a chaotic and confusing manner. They were completely wrong, of course. In fact, Picasso had arranged these pictures in strict chronological order. Painting ‘cubes in the morning and buxom women in the afternoon’ (as one condescending critic put it), he’d been working across a range of contrasting genres at all times.

Apart from these misguided gripes, the show was a huge hit, attracting nearly 35,000 visitors in six weeks. Jung dismissed it as ‘schizophrenic’ but he was in a minority. Most people loved it, including Beckmann and Kirchner, who travelled from Germany to see a show that would have been considered degenerate in their own country. Berlin was in the throes of an election campaign that put Hitler into the Reich Chancellery a few months later. One of his first acts was to fire the liberal director of Berlin’s National Gallery.

Despite this gathering storm (or perhaps, in part, because of it) the Zurich retrospective was one of the first shows to attract a mass audience beyond the cognoscenti. Yet in spite of the crowds and the rave reviews, commercially it was a failure. The Great Depression had brought the international art market to a standstill, and Picasso sold only one painting — to the Kunsthaus itself. Even then, Wartmann managed to beat him down from 25,000 Swiss francs to 15,000.

If Wartmann had bought the lot in 1932, his beloved Kunsthaus would now have the world’s greatest Picasso collection. Instead, these 225 masterworks were scattered across the globe, and it’s taken five years to reunite a representative array of them. Only one has certainly been destroyed, but several have gone missing, and considerably more are locked away by owners who are unwilling to let us see their wares. Thankfully, lots of private collectors have lent their precious pictures, as have numerous municipal galleries the world over. There are 74 works, all from the original exhibition, and though quite a few are familiar there are a good many that are on public show for the first time in years.

British visitors will recognise the Tate’s ‘Girl in a Chemise’, and anyone who knows Paris or New York will recognise many more. However, you’d need to be extremely well travelled to be acquainted with all of them. The fresh juxtapositions are most thrilling. I’d seen one of the Barcelona paintings in Barcelona and another in Vevey, on Lake Geneva, but I’d never seen them side by side. It feels so personal and intimate. As the show’s curator, Tobia Bezzola, puts it, ‘This is Picasso by Picasso.’ It’s not quite the show you would have seen in 1932 but it comes very close. Its finale is the biggest picture in this show (and the original show) — ‘The Artist And His Model’, a haunting canvas more than two metres square that usually resides in Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Bringing it here was a discreet diplomatic triumph, a hopeful sign that today, as in 1932, art can transcend the biggest ideological barriers. A few months after this show, Central Europe succumbed to the madness of the Third Reich — but when that storm had passed, Picasso was still painting.

So what do we learn from this show that we wouldn’t learn from a complete retrospective? ‘What’s completely missing is the political Picasso,’ says Bezzola. ‘There was no trace of that in 1932.’ This was still a few years before ‘Guernica’. Without it, his work seems a lot less strident. There’s an optimism about this art that’s absent in his later years.

If you want to see this show, you’ll have to come to Zurich. Like the original, it’s not travelling on elsewhere. Yet for art lovers, Zurich is an unexpected treat. The Kunsthaus boasts the world’s biggest collection of Giacometti and the largest haul of Munch outside Norway, and this modest metropolis is home to more than a hundred private galleries. Will any of these produce an artist as universal as Picasso? I doubt it. Modern art has become introverted, a reflection of our times. Yet the number of new galleries shows that, a lifetime later, art in Zurich is still a surprisingly potent force. ‘All I have ever made was made for the present, with the hope that it will always remain in the present,’ said Picasso. Wandering around this wonderful exhibition, the pictures he brought here nearly 80 years ago still seem bang up to date.

Comments