When she was four, Anne Sinclair had her portrait painted by Marie Laurencin. It is a charming picture, a little dark-brown-haired girl with a white bow, very blue eyes and a white and pink striped blouse, and it was commissioned by Sinclair’s grandfather, Paul Rosenberg, one of the handful of most influential Parisian art dealers of the 1920s and 1930s. More interested in politics than family history, Sinclair — for 13 years the host of the prestigious French weekly television news show 7 sur 7 — waited until she turned 60 to explore the trunks of papers in her mother’s attic. What she found was a remarkable archive of letters, bills, cuttings and telegrams, throwing light not only on her own family fortunes, but on the corruption and venality of the French art world during the years of German occupation and the Vichy government.

Paul Rosenberg was born in Paris in 1881, the son of a Jewish grain merchant from Bratislava who had emigrated to Paris and opened an antiques gallery near the Opéra. Here he began to collect and sell paintings by Monet, Manet, Renoir and Cézanne. Having joined his father’s business at the age of 16, Rosenberg spent his days in museums and art galleries, teaching himself to identify what he thought most important in art.

When he opened his own gallery at 21 rue de la Boétie, he decided that he would buy and sell only what he himself loved. He turned the mezzanine over to Renoir, Dégas and Rodin, and filled the first floor with the lesser known Laurencin, Braque, Picasso and Matisse, hoping that the former would help finance the latter. Dali, Magritte and Miró he would not show, saying that surrealism was not ‘sufficiently pictorial’. Mix up your exhibitions, he told a niece, in such a way that they ‘attract the whole of your clientele, the part of it that considers itself advanced and the other more conservative part’.

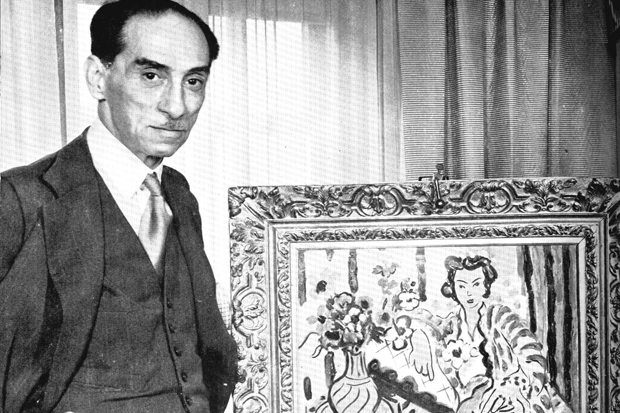

Of all the painters he collected, Picasso was his greatest love. The two men, born the same year, were friends as well as colleagues, and when Picasso was looking for a house in Paris, he and his wife moved next door, to 23 rue de la Boétie. In his letters, Rosenberg addressed Picasso as ‘Pic’. For him, as for his other most admired artists, Rosenberg acted as adviser, agent, even travelling companion. He gave them three-week-long solo exhibitions, hanging each picture himself, and he watched over their finances. Rosenberg was a thin, elegant figure, with what a colleague somewhat unflatteringly described as a ‘fox’s face with too short a muzzle’.

When war was declared, Rosenberg fled south, hiding a number of his pictures in Tours under a false name, others in a bank vault in Libourne, before making his way to the US. Even so, in the orgy of looting that followed the arrival of the Germans in France — galleries and private collections, especially those belonging to Jews, were speedily ransacked, sometimes with the help of predatory rival dealers, and their contents loaded on to trains to Germany — some 400 of his most valuable paintings disappeared.

After the war, all but 60 were eventually retrieved, many as the result of lawsuits. It was only in the 1960s and 1970s, when the full extent of French collaboration with the Nazis began to be known, that the secret deals made by the collaborationist dealers emerged. Before he died, in gratitude for having been offered refuge, Rosenberg donated part of his collection to American museums; others went to French galleries.

Though Rosenberg returned to spend time in France after the war, he never went back to his gallery. As Sinclair describes, the building had been commandeered by the French police intelligence services before passing into the hands of the infamous Institut d’Etudes des Questions Juives, the propaganda arm of Théodor Dannecker’s Gestapo Jewish section. It was here that was planned the highly successful exhibition at the Palais Berlitz in 1941, with its poster of the caricature of a long-nosed, thick-lipped man, with the claws of a bird of prey clutching a globe.

Anne Sinclair set out to write not a biography of her grandfather, but rather an act of homage, recording her own journeys into her family’s history in a ‘series of impressionist strokes’. For all its somewhat disjointed narrative, My Grandfather’s Gallery paints a vivid portrait of a moment of exceptional brilliance in French artistic life; and a sadder and more depressing one of the speed and greed with which it was so brutally destroyed, and the efficiency with which these deeds of destruction were covered up and forgotten.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £12.99 Tel: 08430 600033. Caroline Moorehead is the author of Village of Secrets: Defying the Nazis in Vichy France.

Comments