Seconds before resigning the decisive game of the world championship, Ian Nepomniachtchi’s hand, trembling with emotion, involuntarily toppled the captured pieces at the side of the board. It was a crushing disappointment to lose a match in which he had taken the lead on three separate occasions, and come agonisingly close to an almost unassailable lead in game 12 (of 14).

Days after the match ended, ‘Nepo’ posted a splendidly ambiguous tweet: ‘Although blind chance sometimes decides the fate of a particular game, it can hardly prevent you from becoming the strongest chess player’ – followed by an emoji of a man in the lotus position. I still can’t decide what he meant. Was it a bullish assertion about the future? ‘That tiebreak game was an unlucky break, but I’ll be back.’ Or a statement of humility? ‘We played 18 games and I missed so many chances – I wasn’t up to it this time’. He so often evinces both brash confidence and searing self-criticism that it could be either, or both.

Speculating on whether these sporting moments are determined by chance or by destiny is part of the joy of being a spectator. One can, of course, flatter oneself either way – some fancy the dice spinning before their very eyes, while others bask in the unveiling of a historical truth. It is amusing to recall the twists of fate which made Ding’s path to the title match even possible. Almost inactive during the pandemic, he failed to qualify for the 2022 Madrid Candidates event, but a place opened up after the Russian Sergey Karjakin lost his spot after spouting political bile. Though Ding was the highest-rated player available, he hadn’t played enough games to be eligible, so crammed 28 into one month to pass. Nepomniachtchi was the clear winner of the Candidates, and Ding’s second place (he beat and overtook Nakamura in the final round) only assumed any significance after Magnus Carlsen’s abdication.

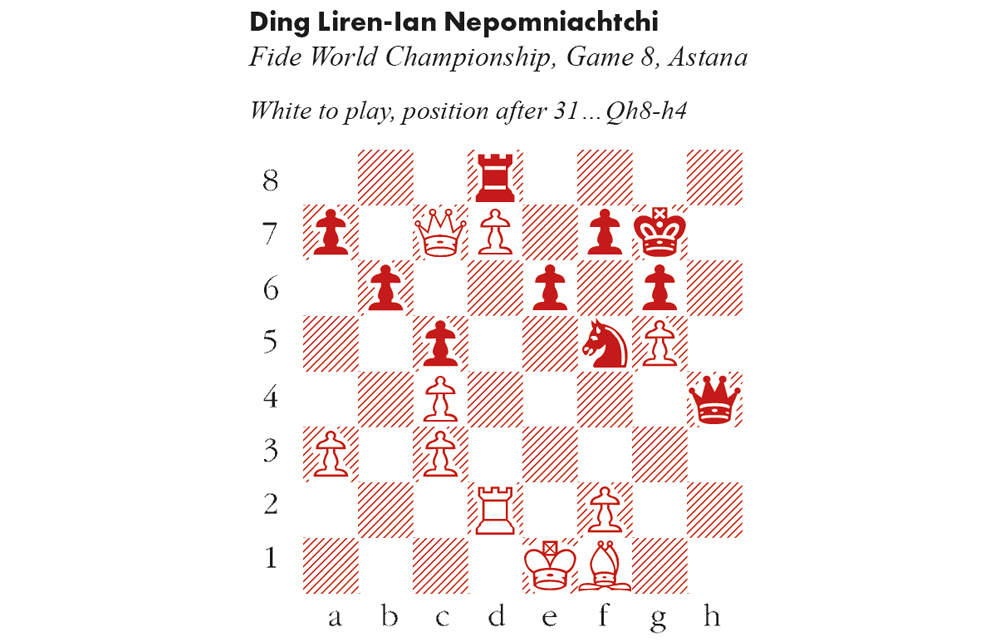

Ding was philosophical in victory, noting how narrow was the margin, but how divergent were the consequences for his life. His lowest moment came after the eighth game (below), in which he passed up a golden opportunity to level the score. He was contemplating retirement if he lost the match, but after winning he expressed his intention to build a strong team and become more professional in his approach: at several moments he had looked far less ready than Nepo for the rigours of world championship matchplay. But Ding paid tribute to his second in Astana, Richard Rapport, whom he credited with infusing creativity into his opening play. Ding was particularly ambitious at the start of game 8, and in the position below his powerful d7 pawn gives him a large advantage.

Ding Liren-Ian Nepomniachtchi

Fide World Championship, Game 8, Astana

Nepomniachtchi is in dire straits, so his last move 31…Qh8-h4 was a calculated risk. Black appears to threaten perpetual check, starting with Qh4-e4+. Ding mistakenly trusted this, spending just a couple of minutes over 32 Kd1. In fact 32 Qxd8! Qe4+ 33 Re2 Qb1+ 34 Kd2 Qb2+ 35 Kd3 Qb1+ 36 Rc2 and now 36…Qxf1+ 37 Kd2! plans to escape via d2-c1-b2, or 37…Nd6 38 Qf6+ Kh7 39 Qf4 wins comfortably. Alternatively, 36…Qd1+ 37 Ke4! Qxc2+ 38 Bd3 Qxf2 39 Qf6+ Kh7 40 Qxf7+ Kh8 41 d8=Q mate. These calculations are challenging, but well within Ding’s capabilities. Qxg5 33 Kc2 Qe7 34 Bg2 e5 35 Be4 Nh6 36 Qxa7 Ng4 37 Bf3 The final mistake. 37 Bc6 would maintain the pressure. Nxf2 38 Rxf2 e4 39 Re2 f5 40 Qxb6 Rxd7 41Qb8 Qd6 42 Qxd6 Rxd6 43 Bxe4 fxe4 44 Rxe4 Kf6 45 Re8 Draw agreed

Comments