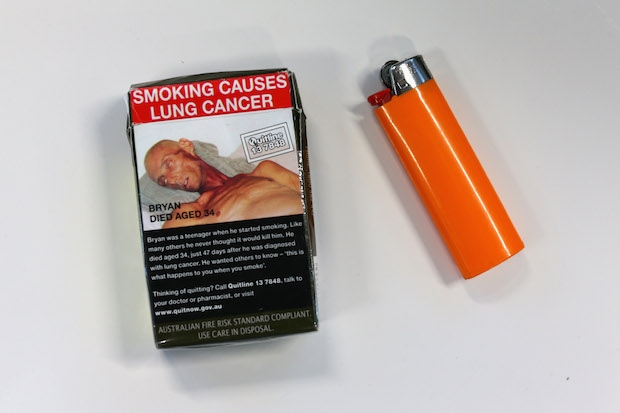

Only one country in the world—Australia—has experimented with standardised packaging for cigarettes. Quite reasonably, people said that until hard evidence emerged from there it would be unwise for the UK Government to introduce a policy that could have serious consequences in terms of crime, compensation for deprivation of intellectual property rights and breaking of our world trade obligations. Critics argued that this was little more than a delaying tactic. But Sir Cyril Chantler, who conducted a review of the public health effects of introducing standardised packaging, reported in April that it was ‘too early to draw definitive conclusions’ from what had happened in Australia.

He also acknowledged that the research he rested his own conclusions upon had been based on people’s ‘stated intentions’ and that such research has to be used with care. He conceded that his findings were essentially ‘indirect and ‘speculative’.

Well, it seems that industry sales data is now emerging in Australia. And in its wake, so is a growing consensus that the previous Labor government got it wrong.

Last week, eighteen months after the Australian Government’s plain packaging laws came into force, new data was published in the Australian, the respected national newspaper, which showed that tobacco sales increased by 59 million individual cigarettes or roll-your-own equivalents last year. This increase is modest – 0.3 per cent – but goes against a 15.6 per cent fall in tobacco sales over the previous four years. This evidence—with the changing consensus opinion in Australia on plain packaging—should, at the very least, prompt the UK Government to pause for thought before implementing similar legislation.

It is no surprise that, given the increase in cigarette sales after the introduction of plain packaging, that the Australian’s editorial stated: ‘Perhaps nannies are hazy about markets.’ It further argued that:

‘Plain packaging deprives tobacco firms of valuable assets — the intellectual property of their marketing. That is a bad precedent. Similar moves could follow against alcohol bottles, food trademarks and much else.’

It’s time for a rethink in this country too. An investigation this month by the Sun revealed that foreign criminal gangs (who are already flooding Britain with dangerous fake cigarettes) are gloating that they will profit even more if standardised packaging is introduced in the UK. They told the Sun’s undercover team that ‘the switch to plain packaging will make their fraudulent trade easier, cheaper and more difficult to detect.’ Indonesian forger Fauz Firdaus even punched the air and exclaimed ‘plain packaging … I support the UK Government!’.

We have made encouraging progress on reducing smoking in the UK and there is still more we can do, for example, putting a ban on smoking in cars. I supported that move because the evidence was there. But to date plain packaging can’t be shown to be more than a risk, and one with criminal and financial implications for the UK.

We should look instead to Germany’s example. Its education campaigns have, in just a decade, reduced smoking rates among the young by more than half. I welcome current UK anti-smoking educational initiatives and believe we should do even more to continue to engage in public health programmes that lead individuals to make better decisions.

Instead of rushing ahead with a policy that is high on grandstanding but low on evidentiary support, let’s build on the progress we’ve made with proven and effective public health programs.

The government can bring in plain packaging whenever they wish. Parliament has passed enabling legislation which means there will be no further votes on the matter. But given standardised packaging’s apparent failure in Australia and the impact it could have on serious crime and our long term economic plan, the Government should go carefully before rushing into the introduction of standardised packaging here.

Comments