There is a picture book, by the excellent David McKee, of which my youngest child was very fond. It’s called Two Monsters, and its protagonists are, as promised, two monsters. The blue one lives on the west side of a mountain, and the red one lives on the east side of the mountain. They communicate verbally but never see each other.

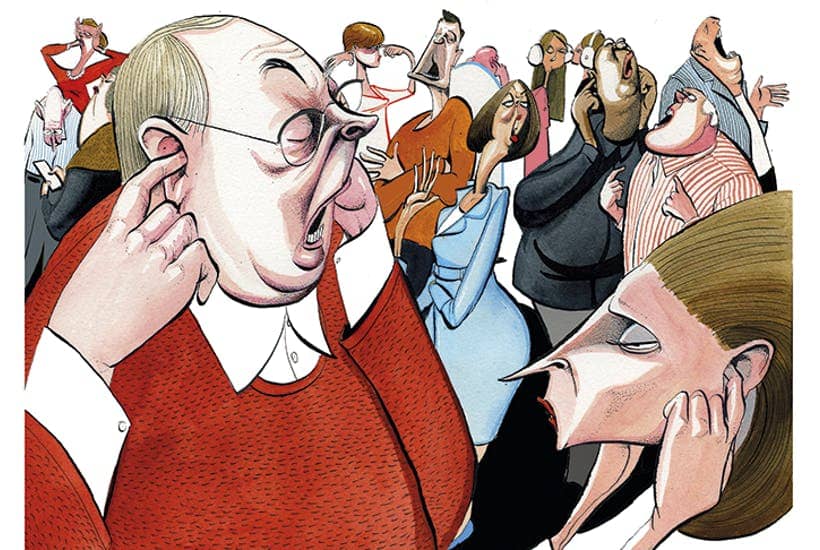

It all kicks off when one evening the blue monster calls: ‘Can you see how beautiful it is? Day is departing.’ The red monster shouts back: ‘Day departing? You mean night arriving, you twit!’ Cantankerous words are exchanged before bedtime and both sleep badly. The following morning the blue one shouts: ‘Wake up, you numbskull, night is leaving.’ Red responds: ‘Don’t be stupid, you peabrain! That is day arriving.’ The creatures – to the intense delight of young readers – spend most of the rest of the book hurling insults and boulders at one another over the mountain.

I don’t know if David McKee was aware when he wrote it that he was sketching an allegory for the most bitter and futile rows that would come to occupy the international political class. More and more, we are arguing not about things but about the definitions of words. Who could have known that the definition of ‘woman’, for instance, would become a bear-trap for politicians on the Sunday morning talk shows?

Defining abstractions to suit yourself, and then making a cause out of opposing them, is tilting at windmills rather than doing practical politics

This week David Miller, a sociology professor at the University of Bristol, lost his job. He reportedly called for ‘the end of Zionism’ and said that it’s ‘fundamental to Zionism to encourage Islamophobia and anti-Arab racism’. We may all form our own opinions about what Professor Miller has in his heart. But ‘Zionism’ is a prime instance of a word which is used entirely differently by those on different sides of a political boundary-line.

Those who identify themselves as ‘Zionists’ will tend to mean that they support the existence of a Jewish national homeland; those who use ‘Zionist’ as a term of abuse and deprecation (leaving aside those for whom it is simply code for ‘evil Jew’) tend to think it means someone who rejoices in seeing Palestinian homes bulldozed, Arab children killed and illegal settlements placed wherever Israel fancies having them.

You can find many blameless examples of the former, and I dare say you can find blameworthy examples of the latter, and there are probably a fair number of more or less reasonable positions in between – but it’s an awful lot of ground for one word to cover.

Defining abstractions to suit yourself, and then making a cause out of opposing them, is tilting at windmills rather than doing practical politics.

Especially vituperative are the rows that arise over words that all agree represent an unquestioned good (‘freedom’, say, or ‘democracy’), or an unquestioned evil (‘racist’, say, or ‘fascist’) – and yet which are freely applied without being defined to mutual satisfaction. ‘Freedom’ is a doozy that way. Isaiah Berlin warned us decades ago that this one was tricky; that positive and negative liberty – ‘freedom from’ and ‘freedom to’ – not only aren’t the same thing but are frequently in conflict.

Yet anti-lockdown campaigners or US gun-control opponents invoke their ‘freedom to’ as a simple good; while their opponents might plausibly argue to be in favour of ‘freedom from’, be it from dying of coronavirus or being gunned down in primary school.

And my word has ‘democracy’ been through the mill. From the endless Brexit punch-up to relitigating Trump/Clinton to the arguments over changes to the internal rules of the Labour party, everyone claims to have ‘democracy’ on their side. But democracy comes in more flavours than a slice of cassata ice cream. Representative democracy, direct democracy, first-past-the-post, proportional representation, popular vote, electoral college system… there are respectable arguments in favour of each and all of them, but rather than disentangle their complex pros and cons we prefer to decide that whatever we like is ‘democracy’ and to hell with the other guys.

Or take, even, something so apparently straightforward as ‘whiteness’. Most people will think that in a racial context it refers to skin colour, but some proponents of critical race theory (CRT) have – in my opinion unhelpfully – extended the definition to mean something like ‘hegemony’. By this token, brown people hostile to CRT can be deemed to be white; and inveighing against ‘white feminism’ is not racialised hostility but a comment on an ‘ideology’ that has nothing intrinsic to do with skin colour at all. It’s hardly a surprise that non-academic white folk who haven’t cottoned on to this new extended definition, on hearing ‘white privilege’ denounced, think they’re the victims of reverse-racism. Which inevitably kicks off another definitional argument about whether ‘reverse-racism’ exists – and so, ding dong, the boulders fly.

Oh yes. Those monsters in the storybook. Red and blue end up hurling so many rocks at each-other that they demolish the mountain – and catch-sight of each-other across the rubble-strewn plain just as the sun is going down. ‘Incredible,’ says the first monster. ‘There’s night arriving. You were right.’ The second monster drops his own boulder. ‘Amazing,’ he says. ‘You are right, it is day leaving.’

Having realised that the whole cause of their enmity was that they were describing the same phenomenon in different words, the two sit down to enjoy the view together. Some hope of our own red monsters and blue monsters doing the same.

Comments