In 1778, Louis-Sébastien Mercier, dramatist and author of the early science fiction novel L’an 2440, claimed that only a small minority of writers in ancien régime France lived by their pens: ‘One exclaims everywhere that the number of authors is enormous… But in fact, there are not more than 30 writers in France who make writing a career.’ The rest needed patrons, protectors, pensions, privileges and sinecures to scrape a subsistence, or else were reduced to peddling libels and pornography, or spying for the police. In the absence of copyright or royalties there was plenty of piracy, and without a network to depend on – an aristocrat, a royal mistress, an influential salon member – a writer could easily sink to what the American historian Robert Darnton calls ‘the bottom of the literary world’. This was France’s version of Grub Street, populated by Voltaire’s pauvres diables (poor devils) and les Rousseau du ruisseau (Rousseaus of the gutter).

In 1789, there were perhaps 3,000 writers in France ready to ‘explode in a revolution’

Who could call themselves a writer in France before the Revolution of 1789 upended literary culture along with almost everything else? In The Writer’s Lot, Darnton adopts the criterion of La France littéraire, ‘a guide to writers and writing that was published at regular intervals throughout the second half of the 18th century’: anyone who had published at least one book was considered a writer. But ‘book’ was not tightly defined, and La France littéraire included ‘some works that would be considered rather ephemeral today’, such as sermons, medical tracts and academic discourses. Darnton calculates that in 1757 there were 1,187 known writers in France and that by 1784 this number had more than doubled to 2,819. The deaths of Rousseau and Voltaire within two months of each other in 1778 ‘touched off a new wave of enthusiasm for the cult of the philosophe’, and encouraged the next generation of scribbling hopefuls to dream of living by their pens.

Darnton estimates that by 1789 there were 3,000 writers in a nation of 26 million ‘about to explode in a revolution’. Very few of them could earn a living, but, according to Mercier, they agreed on ‘essential principles’, rejected ‘arbitrary power’ and produced ‘a unanimous protest’. Darnton is more sceptical. Given ‘the tendency of authors to fight one another over all sorts of subjects’, were 3,000 ancien régime writers really united on points of principle on the eve of the French Revolution? Despite his scepticism, he quotes Mercier’s claim that the term sans-culotte first referred to one indigent writer in particular, ‘Nicolas Gilbert le sans-culotte’, who died in 1780 too poor to afford decent clothing. Afterwards, the term was used by rich people to deride inelegantly dressed authors, the pre-revolutionary forerunners of the militant sans-culottes who supported the first French Republic in 1792.

Was there then a short step from the Republic of Letters to French revolutionary republican politics? Fifty years ago, Darnton began his brilliant career by insisting on the part the French Grub Street writers played in the ideological origins of the French Revolution. He remains unpersuaded by ‘historians who argue that some form of Enlightenment discourse brought down the ancien régime and determined the course of the Revolution’. After devoting decades to studying ‘printing, pirating, censorship, bookselling and the politics of publishing’, Darnton has finally come full circle back to the writers.

He follows the careers of three authors, each at a different level in the world of letters, into the maelstrom of the Revolution. As a young man, André Morellet did not consider himself ‘to be in a position to live from the métier of a man of letters’. Instead, he became tutor to the son of a marquis, was rewarded with a pension, but ended up in the Bastille after ridiculing an aristocrat for religious bigotry. In his retrospective memoirs he wrote: ‘I saw the walls of my prison lit up by the possibility of some literary glory: persecuted, I would be better known.’ He narrowly survived during the Revolution after trying but failing to rescue the archives of the Académie française from the revolutionary attempt to extinguish ‘the aristocracy of the mind’.

François-Thomas-Marie de Baculard d’Arnaud, known as ‘the dean of the poor devils’, also did time in the Bastille and survived the Revolution. He had one successful melodramatic play, Les Amants malheureux, ou le Comte de Comminges, that was performed in 1791 and again in 1793 during the Terror. The stage set was a crypt with an open grave and scattered skulls. When he died in 1805, after writing dozens of sentimental novels, d’Arnaud was destitute.

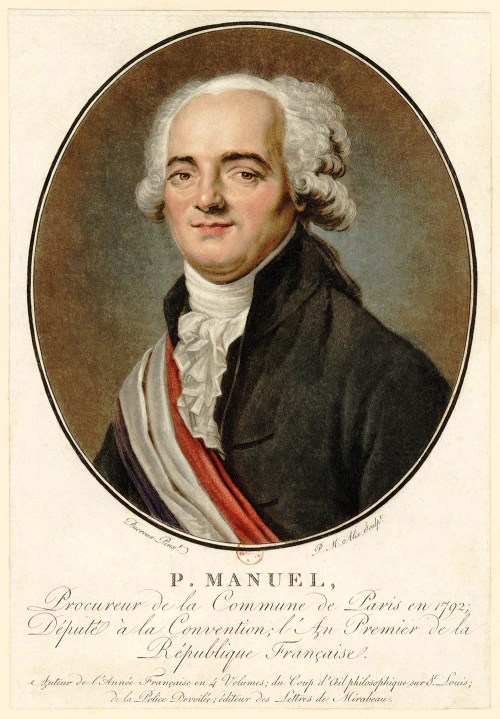

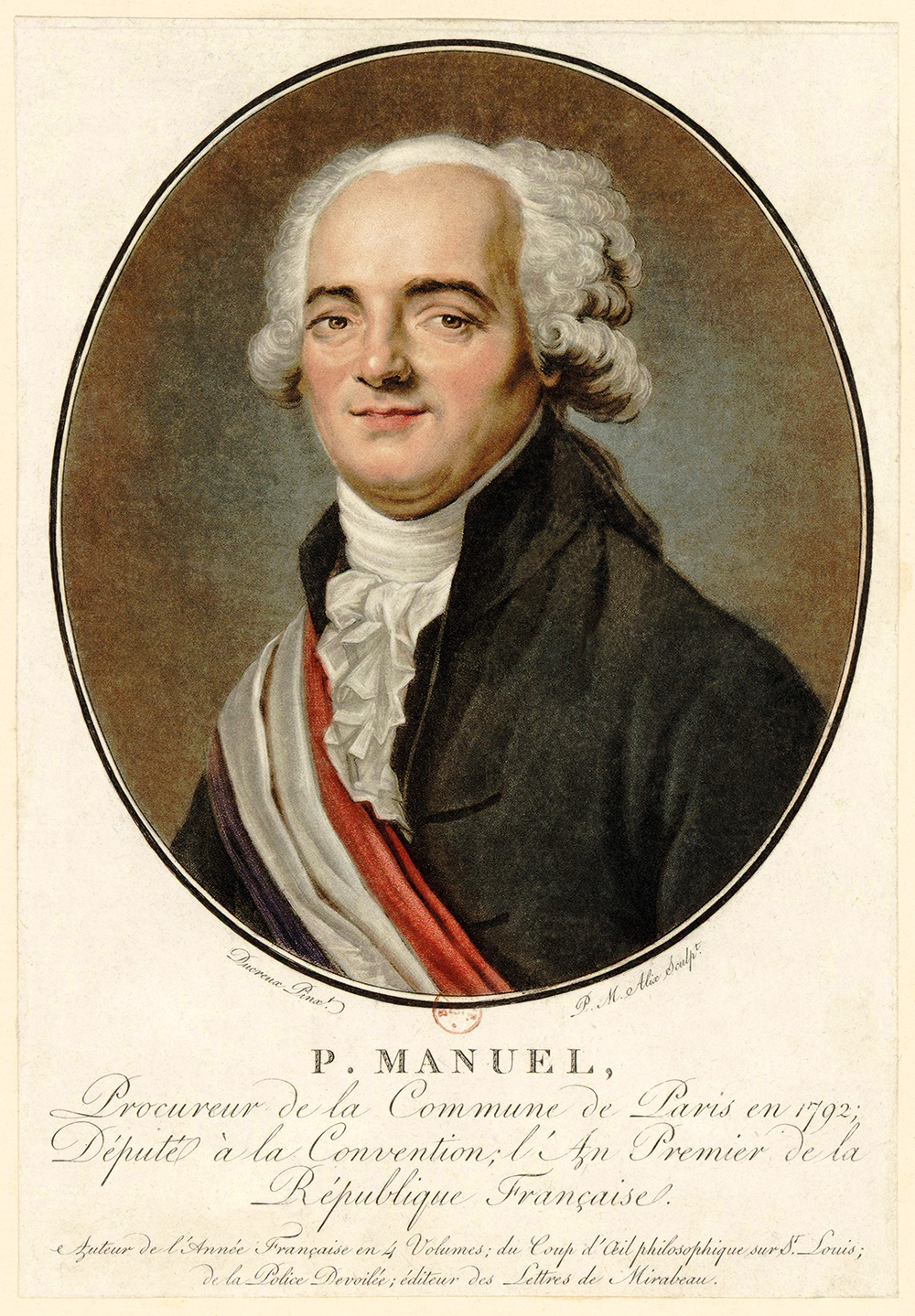

Pierre-Louis Manuel was a pamphlet peddler in 1789. He made money during the Revolution from publishing the archives of the Bastille and became powerful as prosecutor of the Commune but was guillotined in the first phase of the Terror, like other writers – Brissot, Carra, Gorsas, Louvet de Couvray – who had ‘developed new careers as journalists and politicians after 1789, only to be cut down in 1793’.

Darnton explains that by the end of the century the prestige of writers was ‘at its zenith’. The revolutionaries moved Voltaire’s remains to the Panthéon in 1791 and Rousseau’s followed in 1794. Enemies in life, companions in death, these two literary godfathers to the Revolution bestowed different intellectual pedigrees. Voltaire gave the revolutionaries anti-clericalism; Rousseau gave them egalitarianism.

Darnton concludes:

The Rousseauism of Robespierre and the other radicals of 1793-94 shows how literature fed into a phenomenon that marked history at the end of the 18th century and is still alive today: the mobilisation of ideas and passions in the form of a cultural revolution.

Meanwhile, at street level, there were hundreds of writers struggling to survive, buoyed by the illusion that they too might write something worthy of immortality, or at least earn their daily bread.

Comments