Charles Dickens’s description of Cobham Park, Kent, in The Pickwick Papers makes it seem a perfect English landscape. Among its ‘long vistas of stately oaks and elms’, he wrote, ‘occasionally a startled hare’ ran with ‘the speed of the shadows thrown by the light clouds’. It was there on the morning of 29 August 1843 that a butcher from Rochester got a nasty surprise. He discovered the corpse of an apothecary named Robert Dadd; he had been battered and stabbed to death by his son Richard.

There is no doubt that Richard Dadd was far from sane. On the other hand, his loss of mental balance — though very bad in its consequences for his father — was the making of Dadd as an artist. Only after he became a homicidal maniac did he turn into a major painter.

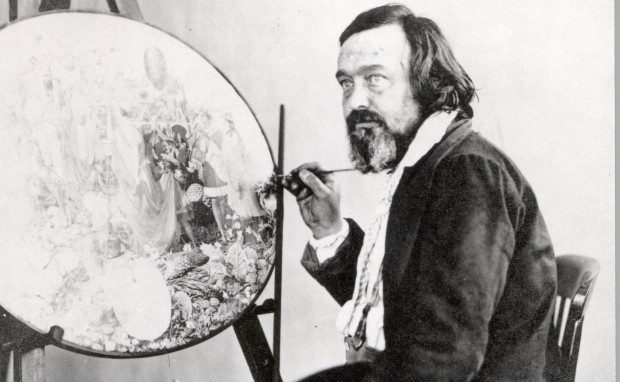

A 26-year-old star of the early Victorian art world when he committed this terrible crime, Dadd spent the remaining 43 years of his life in psychiatric institutions, first Bethlem (or Bedlam) Hospital in London and then the newly founded Broadmoor. While living in Bedlam, Dadd, very slowly, produced his two masterpieces — ‘Contradiction: Oberon and Titania’ (1854–8) and ‘The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke’ (c. 1855–64) — both of which are on show in an exhibition at the Watts Gallery at Compton near Guildford: The Art of Bedlam. This is small in size but, because of the nature of his art, it amounts to something approaching a retrospective. Its curator, Nicholas Tromans, is also the author of a book, Richard Dadd: The Artist and the Asylum, which reveals much new information about those long years of incarceration as a ‘criminal lunatic’.

In his greatest pictures Dadd seems to shrink space. The closer you look, the more you see. For example, in the centre of ‘The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke’ there is seated a white-bearded Gandalf-like sage identified by Dadd as an ‘arch-magician’. After peering closely for a while, you notice a tiny cavalcade — according to Dadd, Queen Mab and her retinue of ‘female centaurs’ — riding across the brim of his hat.

The whole painting — less than two feet high — is like that. The small figures you notice first of all tower over yet more minute ones, and all of them surrounded by gigantic daisies and grasses: the setting a few square inches of woodland floor. The earlier ‘Contradiction’ is similar in its teeming population, overscale vegetation and airless atmosphere — as if it were taking place indoors under a glass canopy.

‘Bacchanalian Scene’ (1862) has the same close-focus botanical observation and claustrophobic lack of space, but instead of tiny figures it consists of three big faces, jammed together. The eyes of a bearded man to the left swivel towards a young woman in the centre, while the pulpy lips of a satyr protrude greedily in the direction of a goblet he is holding.

Dadd’s descent into insanity during a prolonged journey to the eastern Mediterranean in 1842–43 reads like a story by Edgar Allan Poe. On Corfu he found himself surrounded by a ‘large assortment of pompous ruffians’ with such ‘deliciously villainous faces’ as to ‘turn the brain of a poor artist’ (a description that reminds one of ‘Bacchanalian Scene’). By the time he got to Petra, ‘the excitement of these scenes’ was such that when he lay down at night he ‘really and truly doubted his own sanity’.

On the return journey, in Rome, Dadd felt impelled to assassinate Pope Gregory XVI but found the pontiff (who was paranoid himself) too well-guarded, then spotted the devil disguised as ‘an old English lady in a lavender-silk dress’, looking at pictures in the Vatican galleries. She had a lucky escape.

On the one hand Dadd was violent and demented, yet in other moods, according to his case notes, he could be ‘a very sensible and agreeable companion’ and clearly was creative on a high level. This was the contradiction that intrigued his contemporaries; like our ancestors of the romantic era, we still remain fascinated by the blurred boundary between imagination and derangement.

At the Ordovas gallery, 25 Savile Row, there is an even smaller exhibition testifying to a very different kind of obsession: Lucian Freud’s love for his second wife, Caroline Blackwood (1931–96). They met in 1949 at a ball given by Lady Rothermere, a memorable occasion on which Francis Bacon booed Princess Margaret off stage when she attempted to sing a Cole Porter song.

The brief time he spent with her was one to which Freud returned frequently in conversation. He was enchanted by her nervousness, which led her to chain-smoke so that her nostrils were blackened ‘like railway tunnels’, and her impracticality, which led her to hold matches the wrong way up, so they almost always went out.

The exhibition contains only four pictures, and is well worth visiting to see just one: ‘Girl in Bed’ (1952), one of Freud’s early masterpieces. He records each tiny detail: her anxious, wayward look, the corrugations on her lips, and above all her huge grey-blue eyes. An unfinished fragment of a painting depicts just one of those eyes in which everything — the room in which he is painting, the whole world — seems to be reflected.

Comments