Had the artist Rex Whistler not been killed in Normandy in 1944 at the age of 39, in what direction would his great talent have gone? It is futile to speculate, write Hugh and Mirabel Cecil, the authors of this sumptuously illustrated new biography. But many did. Cecil Beaton thought he would have become another Turner. My mother Caroline Paget, his greatest love (but who loved him without the intensity that he loved her), thought he would have become one of the greatest portraitists of the 20th century and, relishing new ideas in stage design, also one of the most famous designers of his day. All his friends thought that soldiering had changed both him and his art. His work, so often fanciful, rococo and gorgeous, became increasingly darker and more naturalistic.

Rex (he was killed five years before I was born, but he was talked about with so much love all through my childhood that I feel we are on Christian-name terms) was born in 1905, into the respectable middle class, no relation to the celebrated James McNeill. Even before he left school at Haileybury, a remarkable talent for draughtsmanship, along with imagination and humour in its execution, had already become apparent in his work.

After a false start at the Royal Academy, he studied at the Slade, where the redoubtable Professor Tonks became his teacher and mentor. Here he made friends with the exotic and terminally aesthetic Stephen Tennant, who introduced him to the smart, bohemian world in which he was to move thereafter, and where he was in his element. Through Stephen, he met the writer and mystic of Wilton, Edith Olivier, 30 years older than he was, who became his greatest friend and confidante, and whose adoration of him sometimes appears more than maternal. But she understood him, as his own mother never really could.

Edith’s life at the Daye House and the landscape of the park at Wilton — with Palladian bridge and Inigo Jones house — were to be lasting influences; and it was at Wilton, too, that he met my mother and her sister Liz, who drew him into their family, the Pagets, in whose house, Plas Newydd on Anglesey, he was to create his greatest masterpiece. (Whether he was the original for Charles Ryder in Brideshead Revisited, as is often claimed, is doubtful. An ‘idea’ of Rex, perhaps, but Evelyn Waugh was neither a close friend of his, nor did Waugh ever stay at Plas Newydd.)

When Rex was not quite 21, Tonks found for him his first major commissions, the second of which was for the murals (now being restored) that decorate the restaurant of the Tate Gallery. ‘The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats’, as the sequence is entitled, is a narrative jeu d’esprit, where already the fertility of his imagination, his ability to invent original rather than derivative romantic landscapes, the brilliance of his architectural drawing and the sheer fun of it all looks ahead to the brightest future.

The variety of the work which he undertook in the next 12 years dazzles: murals (his most lasting legacy), portraits (his best are in the first rank), stage design (The Rake’s Progress and Love for Love are a delight), advertisements (particularly for Shell), and covers and illustrations for over 100 books. The humour in the detail and architectural splendour of those for Gulliver’s Travels (apart, perhaps from an epicene Gulliver) are by far the best that Swift’s adventure and satire have ever had.

Rex was at his best when painting with love — or at least emotional engagement — as in the portraits of Edith Olivier and her world (that heavenly, evocative ‘Conversation Piece at the Daye House’), some portraits of my mother and other loves (but not the declassée ‘Girl with a Red Rose’, reproduced overleaf; that has always given me the creeps, which was perhaps, the artist’s intention). All the war portraits are superlative, as are the scenes of barracks life, and the stillness of the English country, when Europe was at war.

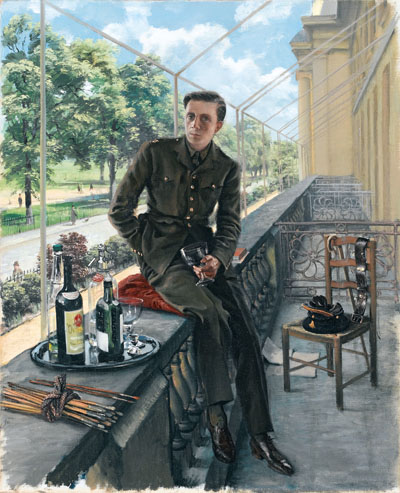

My favourite painting of all is the wonderful ‘Self-portrait in Uniform’ (above), where Rex seems so romantic and sad. He looks, there and in photographs, just like every artist ought to look!

At Plas Newydd, where his employer, Lord Anglesey, was a most laid-back and prompt-paying patron, the mural, his ‘Kingdom by the Sea’ in the 58’-long dining-room, painted on a single length of canvas, shows two towns ‘bristling with domes and columns’, an island with a ruined fort, mountains and a beach. It mirrors, in an extravagant and joyful explosion of artistic invention, classical and romantic fantasy — and family in-jokes, the view of the Menai Straits and mountains seen from out of the window. In it my mother sails alone in a boat with a red sail.

Her inability to return his love as he would have wished was the great sadness of Rex’s life. But she told me that, just after she last saw him, she had decided that she was going to tell him, next time he came home on leave, that she would marry him. And she kept the pink-and-white Renoir dress (with matching parasol) which he had designed for her for the Ashcombe fête-champetre of 1937 until the end of her life.

The visual aspect of this book is magnificent. Angelo Hornak’s photographs of the original paintings are glorious. The publisher, Frances Lincoln, has produced a considerable work of art in itself.

The Cecils’ text is very well organised, exhaustive in research and information, and enjoyable and lively. There is not a single flat sentence. In their final chapter, ‘The Awful Destruction’, an account of his brave but unnecessary death, the writing is especially powerful and moving.

There are a few irritating inaccuracies, however, mostly gleaned from the internet. My mother died in 1976 at the age of 62, not in 1973 at the age of 59, and she spent much of her final two decades with her close friend, the artist Marguerite McBey, not her ‘boon companion’ Audrey Carten.

Tallulah Bankhead (an earlier fling of Rex’s) certainly did not reinvent herself as a ‘television presenter’. She became one of the most famous women in America as the compère and leading personality of The Big Show on radio. Raimund von Hofmannsthal never spelt his name Raimond and — whatever their website may say — I doubt that his father Hugo ever rented Schloss Kammer. The tiresome Misia Sert was not a painter, although her husband Jose-Maria was.

There is a commemorative plaque at the Tate, with a dedication by Osbert Sitwell to the memory of ‘an artist multifarious in aim and accomplishment who excelled in the several arts he practised, and of a man of delightful and endearing personality’. His loss, both to his friends and to the world of art, was an awful destruction indeed.

Comments