When Maurice Broomfield left school at the age of 15, he took a job at the Rolls-Royce factory, bending copper pipes on a turret lathe. That was what you did in Derby in 1931: Rolls-Royce was the town’s biggest employer, and entire generations expected to pass the best part of their lives behind the walls of its 13-acre plant. But Broomfield didn’t stay. Not long into his new job, he saw a photo of an ageing employee being packed off into retirement with a handshake and a gold watch. This was a person who’d never had any real control over his own life; who’d worked when he was told to, and stopped when they told him it was time. Broomfield wanted something else.

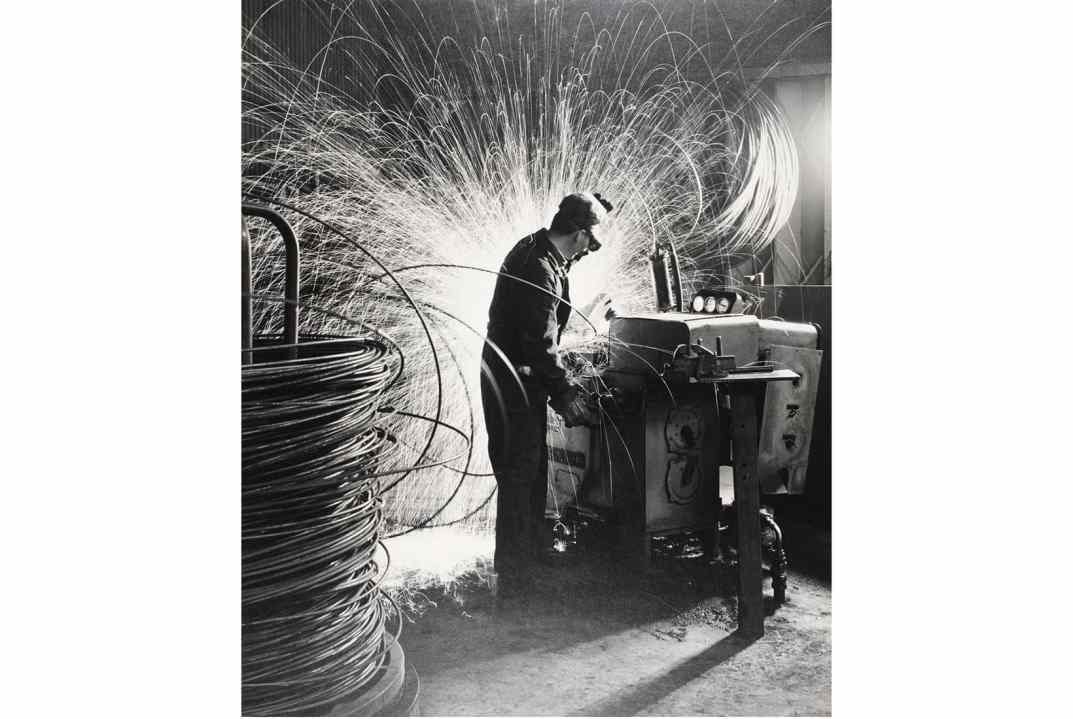

When he returned to the factories after the war, it was as a photographer. He shot workers bottling salad cream in Bermondsey, and buffing a ship’s propeller in Glasgow; in one series of more than 100 prints he turned the camera on the hidden entrails of his own art, documenting the factories where Ilford Ltd made photo paper and glass plate negatives. But his greatest works were the ones made of nothing but heat and fire. In ‘Tapping a Furnace’ (1954), shot at the Ford plant in Dagenham, a single figure stands in a vast empty space, emptying molten steel from a crucible. No light, except the volcanic glow of the furnace: pure livid potential. In ‘Wire Manufacture’ (1964) a worker stands at a machine cutting wire, but the metal coils dissolve into the halo of wild sparks around him. There’s a cathedral-like grandeur in these photos, something Promethean: tiny human figures, in control of so much raw fire. But they were never really in control: Maurice Broomfield was. He made sure of that.

For a moment, the factory workers are frozen as the masters of the world

Broomfield was not a documentary photographer. He was not an invisible observer, merely capturing the world as it is. His images were precisely framed and composed; sometimes work would shut down entirely so he could arrange his shots. For an hour or so at a time, he ran the factories – moving workers around, turning machines off and on, even changing their clothes. In 1966, he visited United Dairies, and decided that the workers’ black boots wouldn’t suit the clean, gleaming image he wanted. He had them all painted white.

Very few of his photos give the impression that anything in particular is being made. The Somerset Wire Company appears to be producing sparks more than wire; in his shot from a paper mill in Northfleet, the paper dissolves into a wash of light and speed. His lens turned all these factories into theatres: places that existed not for the production of cars or wire or electricity, but images.

Critics often compare Broomfield’s images to the art that was, in his heyday, coming out of the Soviet Union. The same reverence for huge machines, the same thrill at industry for its own sake: the people in Soviet paintings aren’t really producing cotton or steel either, but socialism. But Broomfield mostly worked on commission for the factory owners themselves; his photos were used to illustrate company reports. His workers stand heroically alone, faceless, with nothing to suggest they might have any human existence outside the factory gates. There’s certainly no hint of the unfreedom of working-class life, the same thing that sent him fleeing the Rolls-Royce factory in Derby. Still, his admiration for his subjects is obvious. Their skill, their power, the vast forces they control. For a moment, the factory workers are frozen as the masters of the world.

A lot has changed since. There’s a funereal tone hanging over the V&A’s exhibition of his photographs. The short blurb by the door reminds us that ‘many of the factories he photographed – and the communities of workers and skills that supported them – have either vanished or been subsumed into global corporations’. Placards inform us when each site closed. A short film – narrated by Broomfield’s son – shows footage of smokestacks being dynamited, and the concrete husks of what was once British industry. All that grandeur feels different now. Ozymandias in Dagenham, building the ruins of the future.

In the 2020s, we all became miniature Maurice Broomfields: working from home, performing a little theatre of labour for whoever might be watching through our webcams. No dark machinery, just millions of blank faces looking at screens. The art world is still fascinated by technology, but there’s no burning wire or molten steel in sight. Sotheby’s sells procedurally generated ape cartoons; artists live-mint NFTs in converted warehouses. We’ve all become so very, very small.

Comments