Nothing gains headlines for art quite like high prices. A few weeks ago, one of the versions of Munch’s famous image of ‘The Scream’ was sold at auction for £74 million, which couldn’t have been bettered as advance publicity for the Tate’s new show. Admittedly, there is not a single version of that key painting in this exhibition (owners are jittery about loaning them — particularly since one was stolen from Norway’s National Gallery in 2004), but there are plenty of other treats for admirers of this Scandinavian ray of sunshine. Among his favourite subjects were sickness and death, lust and jealousy, fear of sexual disease and even fear of life. A Symbolist who was also a forerunner of the Expressionists, Munch dealt largely in the negative aspects of existence, using art to exorcise his demons. We are now invited to share his horror.

This new exhibition, sponsored by Statkraft, wants to claim him as a great Modernist, rather than a fin-de-siècle figure obsessed with the femme fatale. So we are shown Edvard’s home movies and lots of his black-and-white snaps in order to prove that he was intimately involved with ‘the rise of modern media’, aka film and photography. The accompanying publication (at over 300 pages and with more than a dozen authors it can hardly be called a catalogue) advances these theories with studied intent. But painting is not just about ideas — unless it be that poor relation, conceptual art — it is also about the materials: the canvas and the coloured mud, and the marks made with them. So many exhibition organisers seem to forget this, and plot to make the work of some established master more relevant, in much the same way as the idiot revisionists of the Church of England try to rewrite the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer. Actually, all the public wants is great art, without the fashionable intellectualising.

Munch (1863–1944) straddled the 19th and 20th centuries, and belonged equally to both periods. Some interpretations have emphasised his debt to the earlier period, this exhibition tries to demonstrate his Modernism, but the reality lies between the two. As an artist of greatness he is at once of his time and outside it: he made images which are timeless and which continue to speak to us, often with a stridency difficult to bear. He is the great prophet of alienation, of spiritual and mental torment, totally obsessed with himself and the dissection of his own concerns. Not surprisingly, he makes a particular appeal to this age, in which selfishness has been raised to a sacrament. Yet such is the extremity of his monomania, he makes the self-absorbed posturing of some of our middle-aged contemporaries look trivial.

The first impression of the Tate’s exhibition is that it’s well laid out with plenty of space between exhibits. In fact, with only some 60 paintings on view, together with 50 photographs, this is not a blockbuster, but a reasonably sized show, which makes it relatively easy to assimilate. It begins, appropriately enough, with a room of self-portraits: the well-known and comparatively straightforward 1895 lithograph contrasting strongly with the more manic and violently gouged woodcut of 1912–13 next to it. Opposite hangs a traditionally naturalistic oil self-portrait from 1882 which scarcely suggests the torments to come — though something in the cold gaze coupled with the exceptionally full-lipped mouth promotes disquiet. There are self-portrait photographs here, too, including a hilarious nude one in which the artist appears to be brandishing a sword.

The second room, its walls painted dark red, looks marvellous, principally because the paintings hung on them are predominantly green-blue and flesh pink or yellow. Here Munch’s strategy of painting more than one version of a subject is manifest, with the pairing on opposite walls of two versions of ‘Ashes’, from 1895 and 1925, of ‘The Sick Child’, from 1907 and 1925, and of ‘Two Human Beings: The Lonely Ones’, from 1905 and 1933–5. Comparison is fascinating: sometimes the earlier painting is more compelling (‘Two Human Beings’) sometimes the later (‘The Sick Child’), but always the differences are more rewarding than the similarities. Munch’s interest in vampirism rears its provocative head, offering (perhaps) a taste of Gothic Modernism, while his variants on ‘The Kiss’ promote a viable alternative to Picasso’s cubistic rendering of the actual experience of joining faces. This gallery is one of the highpoints of the exhibition.

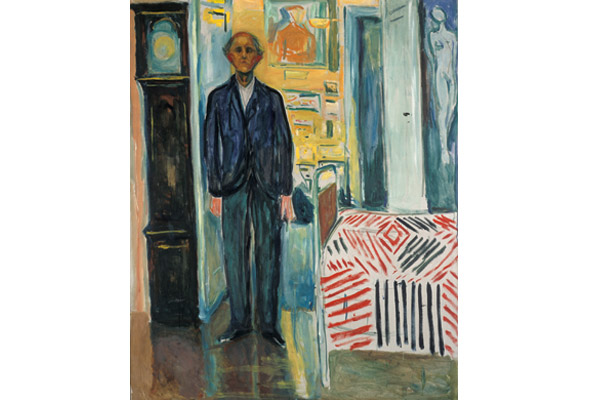

More photos, more paintings of anguish and suffering, relieved by the occasional portrait (‘Thorvald Løchen’, 1917, for example) and landscape. These are interesting, but if you compare Munch’s ‘Street in Asgardstrand’ with a Gauguin landscape, for instance, the Norwegian’s painting looks decidedly thin in terms of colour, drawing, design and even emotional content. Munch is the sickly Northern cousin, always fingering his boils. Am I alone in finding his self-preoccupation rather tiresome? Undoubtedly there are powerful things here, like the images of ‘Jealousy’ and ‘Puberty’ in Room 5, or the ten versions of ‘Weeping Woman’ in Room 6, but I suspect my tolerance for his work is not very high. I’m just not sufficiently interested in him and his neurasthenia and madness. Nor do I find much sustenance in his rather scratchy use of paint. That said, the final room of self-portraits, when Munch looks like John Bratby on smack, has a horrific magnetism to it. The image of the desolate artist standing like a redundant commis waiter between a grandfather clock and a Terry Frost bedspread is more than moderately haunting.

A great contrast over at the National Trust property Flatford Mill, Constable’s old stamping ground, where Simon Carter (born 1961) is showing new work. This Essex-born-and-based artist is exhibiting paintings inspired by Constable. Carter relates the ‘unspoken conversation’ he has with other artists when he’s in the studio, and the recurring dialogue he enjoys with Constable’s paintings. ‘I’m interested in most painting,’ he writes, ‘but I do like the means by which a painting is made, the actual stuff of paint and the evidence of a decision-making process, to be visible.’ He finds this in Constable and, in turn, it is evident in his own work.

He makes drawings in the landscape to investigate appearances and how they may be recorded, but his work is not obviously topographical. The marks made on a sheet of paper in front of the subject are reinterpreted in the studio both as shapes and as signs for things experienced. This transformative process results in images of considerable freedom. Carter has said: ‘I would like the paintings to have the same abrupt matter-of-factness as something out in the world: a concrete step, a piece of breakwater or mud drying and fracturing.’ In watercolour and acrylic he makes statements of a gestural potency that at times recall Auerbach as well as Constable, but which also have their own being and considered identity.

Comments