When Vladimir Putin declared this week that Russia was ‘ready’ to fight a war in Europe, the remark barely seems to have rippled the surface of Britain’s political consciousness. It should have sent a shockwave. The US delegation that had flown to Moscow in the hope of reviving a peace plan left empty-handed. Putin’s message was not bluster but a statement of intent: Russia is preparing for possible escalation now. Yet Britain continues to behave as though danger is tidily scheduled for years in the future, safely beyond the horizon of any present responsibility. It is a comforting delusion, but a very dangerous one.

Britain cannot lead Europe if it cannot defend itself

What Putin understands – and what Britain refuses to face – is that Europe is vulnerable in ways that matter more than tanks or troop numbers. Russia’s president does not need to defeat Nato militarily to cause chaos. As he has already shown through repeated greyzone attacks, Europe’s power grids, subsea cables, energy systems and communications networks offer targets far easier to strike, far harder to defend and politically far more disruptive. Putin’s warning this week was a reminder that Russia knows exactly where our exposed nerves lie.

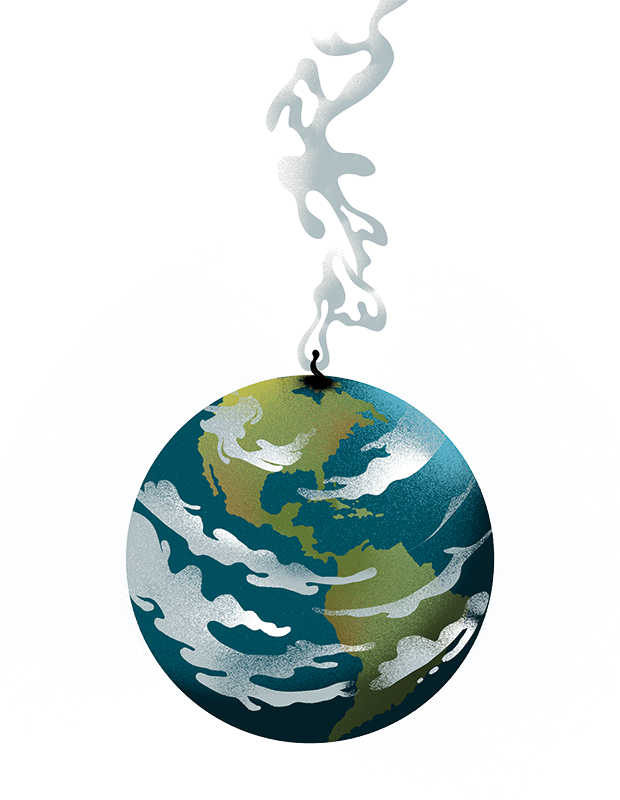

A recent blackout we suffered at home underscored the point. Within a split second, the basic functions of modern life disappeared as our local grid totally collapsed. My family was plunged into the pitch black, with no heating nor even phone access. Ironically, it closely mirrored a wargame I had taken part in recently, in which a hostile actor disabled the UK grid. In that scenario, where the power remained off for days, we predicted mass social unrest; in the real-life example, the outage was only a matter of hours and innocuous. But it illustrated a structural vulnerability: the speed with which a highly digitised society loses its coherence once the power fails. The episode was trivial, but the implications were not.

Ukraine lives this reality daily. For years now, Russia has battered its energy network with drones and missiles. Thermal plants, substations and transmission lines have all been targeted with methodical persistence. The consequences have been brutal: hospitals reliant on generators, districts plunged into darkness, factories stalled, families heating their homes with whatever they can find. And yet Ukraine has adapted because it has no choice. It has hardened its infrastructure, decentralised generation, rehearsed emergency protocols, and taught its population how to function in the dark.

Britain, by contrast, has adapted to nothing – because it continues to believe it never will need to. The Labour government’s insistence that a meaningful rise in defence spending must wait until the 2030s says less about strategy than about wishful thinking, as does its refusal to even consider a national resilience plan that countries like Finland and Sweden have. The idea that the threats facing Britain are a decade away is contradicted daily by events in Ukraine, by Russian cyber activity, and by the hardening axis between Moscow and Beijing.

It is also a reflection of Labour’s unwillingness to confront the structural reforms the country needs. Overspending on welfare and the unchecked growth of state obligations are not abstract fiscal debates; they directly erode our ability to invest in the military, infrastructure resilience and national preparedness. Britain is under-defended, not because the threats are distant, but because the government cannot face the costs of securing the present.

Even if Britain suddenly discovered the political will to take Russia seriously, its strategy toward China would render it meaningless. Our energy transition, defence technology, electric vehicles, wind turbines, batteries and advanced electronics all rely on rare earth elements and critical minerals processed overwhelmingly in China. We talk sternly about resisting Moscow while depending on Beijing – Russia’s most important BRICS ally – for the materials that keep the lights on and the defence sector operational.

In a crisis, China would not hesitate to use that leverage and effectively shut down our defence and energy capabilities. We have neither stockpile nor strategy to keep our soldiers supplied and our lights on; in effect we can only rearm and keep the electricity flowing because of Beijing’s acquiescence, given their control of our supply chains. Yet the government is doing nothing meaningful to reduce this reliance. It cannot even bring itself to call China a threat.

But the deeper danger lies in the scenario that Western governments refuse to articulate: a simultaneous crisis in Europe and the Indo-Pacific. If Russia struck at Europe – especially at a target as symbolically potent as the UK – Beijing would have every incentive to move on Taiwan while the West was distracted. Such a move would immediately cut Britain off from Taiwanese semiconductors, the chips embedded in everything from missile systems to telecommunications to hospital equipment. At the same time, China could restrict exports of critical minerals, paralysing Britain’s industrial base and its already underpowered defence sector.

In such a polycrisis, Britain would face a double shock: a hostile Russia degrading our infrastructure while a hostile China strangled our supply chains. A country unprepared for even a routine blackout would struggle to endure a crisis of that magnitude. This is why stockpiling, supply-chain diversification and national resilience planning are urgent, not optional. The window to prepare closes long before the crisis arrives.

Compounding the danger is the fracturing of the Western alliance. Washington is increasingly exasperated with Germany and other European states over defence spending and Ukraine strategy. The United States is signalling, more bluntly than at any point since the Cold War, that Europe must carry far more of its security burden. In that vacuum, Britain is expected – by allies and adversaries alike – to act as Europe’s leading military power.

But Britain cannot lead Europe if it cannot defend itself. A country without energy resilience, defence industrial capacity, supply-chain security or a national preparedness framework that is ready in the very near future, rather than a decade away, is not a pillar of European security; it is a liability. (And this is before we get onto the critical, lamentable state of our armed forces, with only fourteen heavy artillery pieces and no proper national air defence.) A single well-executed attack on our grid could trigger a cascade of failures – power, communications, water, transport, healthcare – that would unleash chaos on a scale that would undo any national progress this government thinks it has achieved.

Putin’s warning was aimed as much at London as at Kyiv or Warsaw. He understands the gap between Britain’s self-image and its actual resilience. He knows Britain is betting on time – a decade of calm in which to rebuild – at the very moment the world is shortening its timelines.

The question is whether Britain can wake up before the lights go out. If we wait for the crisis to arrive, there will be no time left to prepare for what could be the worst economic and military shock we have seen since the Second World War. And yet still the government will not properly prepare for the peril that so many, including Putin, can see headed our imminent way.

Comments