Is it useful to have Vladimir Putin on your side or not? One would have hoped anybody in the UK Government would have considered this question before, apparently, asking for the Russian President’s help in their battle with the Scottish nationalists over independence.

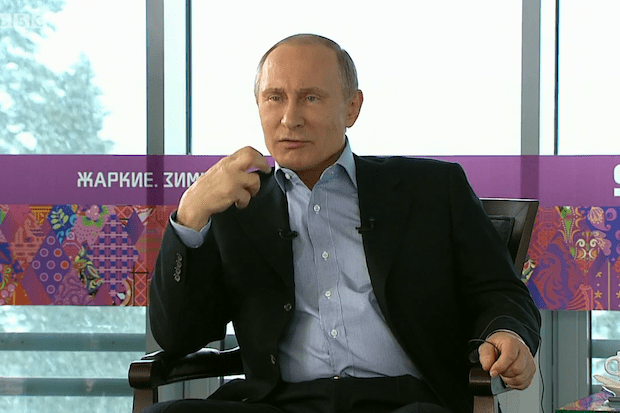

Many people saw President Putin’s intervention in the Scottish independence debate on the Andrew Marr Show yesterday morning. Far fewer, however, are aware of the rather murky background to the exchange between Putin and Marr which seems to have preceded it. For the record, this is what the Russian President said in response to a question from Marr about Scottish independence:

‘It is not a matter for Russia, it is a domestic issue for the UK. Any people have a right to self-determination and now in Europe, the process of denuding national sovereignty in the framework of a united Europe is more accepted.’

But then he added:

‘I believe that one should not forget that being part of a single strong state has some advantages and one should not overlook this. But it’s a choice for each and every people according to their own circumstances.’

Putin was also asked – half in jest – whether he would be prepared to welcome an independent Scotland into the new Russian customs union. And the Russian President replied: ‘I wouldn’t rule that out.’

It is clear that Putin was trying to do two things: he was attempting to stick by accepted practice and not getting involved in the internal disputes of other countries. But, at the same time, he made it clear with his ‘single strong state’ remarks that he favoured the unionist side. It is here that we have to take a step back to the start of the year and a piece on the Russian news agency Itar-Tass.

The former Soviet news agency, which has exceptionally good Russian government contacts, reported that the UK Government was ‘extremely interested’ in world leaders – including Putin – speaking up on behalf of the UK against Scottish separatists. The news agency said that a Cameron aide had reportedly warned Putin that Scottish independence would send ‘shockwaves’ through Europe. Downing Street insisted last night it had not asked Mr Putin to intervene in the debate over Scottish independence.

So we have a report in the Russian media – a claim which Downing Street denies – claiming that an aide to the British Prime Minister had asked Mr Putin to intervene in favour of the Union. Then Putin was asked by the BBC to comment on Scottish independence and rather than just staying out of the debate entirely, which he could easily have done, he made it clear that he favours the unionist side.

If Putin’s intervention was indeed prompted by a request from people in the UK Government, as the Itar-Tass report seemed to suggest, then it has to be asked – what on earth were those Number Ten advisers hoping to achieve?

SNP MEP Alyn Smith spoke for many in Scotland yesterday when he responded to Putin’s intervention by saying: ‘With the best will in the world, I do not think many people in Scotland will take lessons in democracy from Vladimir Putin.’

And that’s the rub. If Barack Obama had spoken out about Scottish independence and warned Scots not to break away from the UK, that would have had an effect on public opinion. Despite his policy setbacks, President Obama still has a great deal of credibility and his would have been a voice worth securing in support of the Union.

But Vladimir Putin? His record on separatist movements isn’t really one to praise or copy and his his approach to gay rights, protest groups and democracy is more likely to antagonise Scots than anything else.

If Downing Street, or anyone else in the UK Government, expended valuable political capital in securing the endorsement of Putin for the anti-independence campaign, the advisers who did that have to ask themselves whether it was really worth it. Putin might be a globally recognisable figure. He might also be, as was pointed out on the Andrew Marr Show yesterday, the third most admired figure in the world (behind Bill Gates and Barack Obama but ahead of the Pope), but that does make him influential in the debate over Scottish independence.

Indeed, I would suggest that pollsters could scour the length and breadth of Scotland for the next nine months and not find a single voter who had changed their mind and decided to vote ‘No’ because it was endorsed by the Russian President. In fact, I would wager that, if anything, voters will be more likely to do the opposite of what Putin suggests and his endorsement might even end up costing the No camp support.

But those people who apparently started this whole process – whoever they were and wherever they came from – must have thought all this through, mustn’t they?

Comments