Renata is a young paediatrician from St Petersburg who, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, keeps crying at work. Her colleagues are baffled: why is she sobbing over Ukrainian deaths when she doesn’t have relatives there? She’s surrounded, she says, by ‘complete incomprehension’ from her fellow-doctors, ‘and I’m quietly going insane.’ Her mother Vinera, a school headteacher, advocates the war, believes the West has its eye on Russia’s ‘inexhaustible wealth’ and that it envies Russia’s people for their ‘spiritual’ values. Renata no longer goes home to visit Vinera: ‘I find her disgusting, she’s a hypocrite, I’m disgusted by her views.’

Galya is a violinist from Samara, locked in a failing marriage to Vladimir, a former state investigator. He’s for the war, she is not. ‘The nightmare is speeding up,’ she says. ‘We’re descending into some kind of Reich, or we’re already there.’ The two now live in separate rooms, meeting in the hallway for arguments in which they shout over each other until the doors slam.

‘At first we were like-minded, we were reading Solzhenitsyn,’ Galya says. ‘And lately he’s even started praising Stalin. I’m shocked. I’m asking, where did you get these terrible ideas?’ Meanwhile Vladimir, sitting by the television news, believes his investigator-past gives him a special nose for falsehood and that he needs to ‘depropagandise’ his wife. ‘It’s very hard,’ he reflects. ‘It’s a process as long as the reunification of Russia and Ukraine.’

In the Urals, lives artist Alisa, who is being prosecuted for her anti-war demonstrations. She wants to show the world ‘that there are different people here’: in future ‘it will be really hard to rehabilitate the word “Russians”’. Tatiana her mother, a chicken factory worker, is appalled by her daughter’s stance. She is torn between the instinct to protect her from harm and the desire to ‘spank her hard with a belt…Give her history…Our Russian history, to study, to analyse, so she can come to normal conclusions.’

These are just three of the seven stories from Andrei Loshak’s hard-hitting documentary Broken Ties (2022). The film is a study of how Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has, for the time being at least, fractured many close Russian relationships and blown families apart.

The split, as shown in the film, is often along generational lines, with parents and grandparents, raised in the Soviet Union, horrified by the children’s lack of patriotism. ‘We can’t be on the side of our enemy,’ says Lyudmila, retired mother of Natalya, a psychologist who has moved to London.

‘I live here. It’s my homeland…Putin is our father, adoptive, not adoptive, doesn’t matter. We listen to him and obey.’ One mother of a war-sceptic, ex-soldier son considers him ‘hypnotised’, and sends her son the text of his military oath, to serve and defend his country. His response is phlegmatic: ‘I ask from whom, from whom to defend?… Everyone needs to be defended from my country now.’

But this is not only about a generation gap. Wives are alienated from husbands, a brother from his sister (raised in Ukraine’s Russian-speaking Mariupol, his sympathies lie in one direction, hers have gone another). As Russian news-clips proliferate in the film, with presenters talking about the ‘mercifulness’ of the invasion or Zelensky’s ‘Nazi ideology’, you feel the biggest divide is between those who watch Russian television and those who don’t. Alisa’s mother Tatiana says she gets all her information from the television: ‘We watch Russia 24… (a state controlled channel) which I trust 100 per cent.’

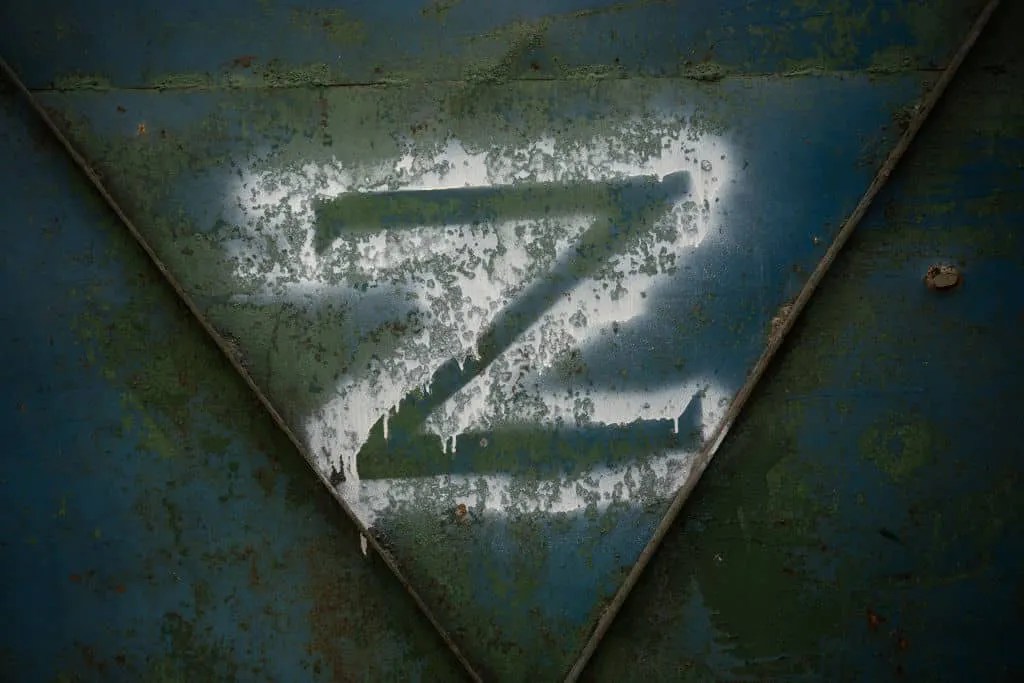

Pro-war Russians are convinced of their country’s rectitude

Psychologist Natalya says her mother has been ‘brainwashed by TV for many, many years’ and that Lyudmila’s started to speak like a TV propagandist: ‘Her regular, vivid speech disappears and she starts talking in standard phrases, cliches.’ She’s identified her mother’s thinking as classic ‘sect’ behaviour and tries patiently to de-programme her – with some success she feels, though Lyudmila, talking to director Loshak, scotches this. ‘I have my opinion and she has her own. She doesn’t live in Russia any more. I don’t think she gives a damn about Russia.’

Meanwhile the pro-war characters are convinced of Russia’s rectitude and, under Loshak’s patient probing, tie themselves in knots. One will not believe Russian soldiers are killing civilians: ‘The Russian soldiers I know are not like that.’

Another, who says the reports of Ukrainian children dying are like ‘a knife to the heart’, blames these deaths on paid soldiers brought in by the West. ‘Are you ruling out that it could be the Russian army?’ asks Loshak. ‘I completely rule it out,’ she says firmly. ‘I will never believe that.’

What you realise as you watch Broken Ties is that Russia itself is a kind of faith, clung to by the characters who seem to have least. One of the mysteries the film throws up is why poverty and patriotism seem to go so closely together. Psychologist Natalya gives us one explanation (though only one of many possible variants), that it’s linked to the fertile ground cults often find in low self-esteem. It’s a case of someone having, she says, no ‘inner strength, inner dignity. And someone tells him, “You really are a saviour, you are saving your country from fascism.”’

Whether she’s right or not, what seems clear from the film is that Putin, over the past two decades, has trained a high proportion of his people to see slavish obedience to his regime as inseparable from virtue, and to confuse questioning the Great Boss’s most drastic and destructive decisions – especially in wartime – with a lack of patriotic spirit.

It’s Loshak’s achievement to show you the human beings that lie behind all this. Again and again we see characters – often in tears – step back from their respective positions, show you a moment’s human doubt and vulnerability, and then return to the dogmatic fray. Renata’s mother Vinera admits she only agreed to do the film – a considerable risk – to allow her daughter to ‘speak out somewhere’ and to ‘feel lighter inside’. Tatiana says of artist daughter Alisa that ‘I was missing her so much, because when we meet we always kiss and hug and now, bang, it’s over… I reached out because I feel it can’t go on like this, we’re family.’

Yet they’re in the minority. ‘We’re going to shoot some military objects and then be friends again,’ Vika from Mariupol says Russian relatives told her at the beginning of the war, leaving her aghast: ‘How can we be friends after something like this?’

And in fact there’s a whole world of damage in Loshak’s film, a picture that’s been shattered altogether. An information service that purveys pure lies, a system that falsely promised, if granted the submission of its subjects, to keep the peace in return. Broken ties between Russia and its ‘brother nation’, between young Russians and their ‘homeland’, between their lives and futures and a cooked up, twisted national narrative now foisted on them. ‘

The demise of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the century,’ said Putin in the deadening old quote. Loshak’s documentary shows you how successful the President has been at reigniting those Soviet values of patriotism and sacrifice among his people. And – perhaps reassuringly – the places where he’s failed.

Comments