If racism presupposes that different ethnic groups cannot live harmoniously together, then segregation puts that theory into practice. Carl H. Nightingale’s Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities, teaches us that separating cities along racial colour-lines, has always concerned one commodity: real estate.

Cities, Nightingale observers, are places where people of several races are meant to come together. But this has not been the case. Instead, residential segregation and city-splitting politics — across the globe — has ensured that by putting a coerced colour-line in place, white-power has remained the definitive norm.

Tracing the trajectory of segregationist politics from 1700, to the present day, Nightingale notes that racial segregationists have consistently worked within three kinds of institutions: governments, networks of intellectual exchange, and the real estate industry. All three have been critically important in the West’s rise to global dominance.

City-splitting politics dates back to when cities first came into being over 7,000 years ago. It was only in the late 18th century, however, that Europeans injected the concepts of race into the political landscape of segregationist politics.

With the advent of The Enlightenment, and inspired by the writings of Francois Bernier — who equated skin colour with cultural characteristics — philosophers like David Hume, and Voltaire, began to project the idea of a hierarchy of races: placing whites at the top, and the darkest races at the bottom.

Once the concept of race acquired a new universal meaning in the late 1700s, leading intellectuals at the time, believed cities had to be split along urban colour-lines, in order for &”civilisation” to progress. This ideological shift into white and black town systems first began in Calcutta, when the parliament in Westminster passed the Regulating Act of 1772 — a law which aimed to overhaul the management of the East India Company’s rule in the vast subcontinent.

As Nightingale poignantly puts it: ‘If modern empire was the first of these institutions, race — which also came to Calcutta via London — was the driving ideology.’

As the 20th century unfolded, and nations grappled with extremist ideologies, such as ethnic-nationalism and fascism, segregationist movements now had the law on their side. This began in the 1920s, in what Nightingale labels ‘archsegregationism’. Two cities that took this extreme approach were: Johannesburg, with its state-sponsored separation, and Chicago, where the method of segregation was advanced by the subtle methods of real-estate markets and housing policies.

South Africa was able to turn to racial legislation to prevent a so called ‘black invasion’. In 1923, a new national-government succeeded in passing The Natives (Urban Areas) Act. This law ensured colour-lines were permanently fixed in the urban landscape. No society in the world had ever produced such a government-legislated system of race-based residential zoning. The nearest the United States would ever get to passing a law on racial discrimination — concerning property — was The Standard State Zoning Enabling Act of 1921.

Both laws, in South Africa, and the United States, meant legislation enabled local authorities to zone their cities. The laws also provided a framework for expanding national government-led urban segregation. The key difference between the two — as Nightingale emphasises — was the place of race in the law. South Africa’s Urban Areas Act celebrated racial discrimination, by explicitly authorizing separate racial zones, degrading black people’s title to land, and discouraging black migration to cities.

In the United States, previous Supreme Court rulings like Buchannan v. Warley in 1917, made it impossible to attack black people’s property rights, or their freedom of movement. However, as the black population continued to grow, so too, did the inner-city ghettos.

The logic of racial theory vs. property values, meant whites who lived near the ghetto, were most likely to pack up and leave. As a result, cities became increasingly divided along racial lines.

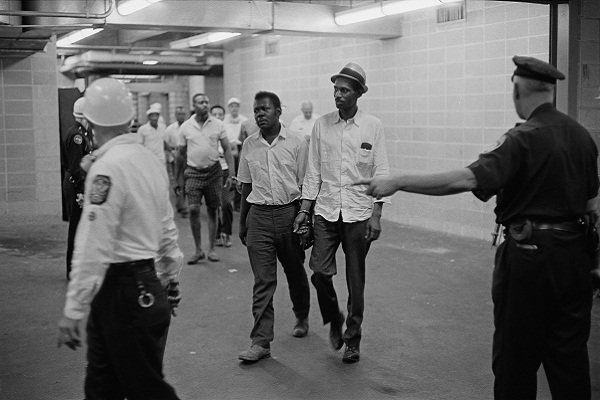

Nightingale’s analysis of racism at work in different political systems is particularly fascinating. Apartheid in South Africa depended on a continual hardening of its iron fist. In the United States, other factors contributed, including: racial pogroms, draconian criminal justice systems, and discriminatory behaviour by the police.

Segregationists survived in the United States by their ability to hide through layers of racial camouflage. If proof were needed which method was more effective in maintaining the politics of urban segregation, Nightingale points to history: the apartheid state has since collapsed. Meanwhile, in the United States, colour-lines continue to play an integral role in the housing market.

Whatever country, or era, he scrupulously examines, Nightingale’s narrative consistently labours the same point: segregation is a form of class war, and all racial theory, ‘whether social- Darwinist, eugenic, sanitary, moralistic, quotidian, or downright idiosyncratic ─ led directly to one subject: property values.’

Segregation: A Global History of Divided Cities by Carl H. Nightingale is published by The University of Chicago Press

Comments