Tom Brown’s Schooldays is a depressing book. It’s hard to see why anyone would encourage their child to read it before starting school, particularly Rugby, where the story is set. Tom Brown’s peers stand in the window near the school gates, surveying the town as if they own it. They fight behind the chapel, where the masters cannot see them, and bully and fag, day and night.

Writing in The Spectator in 1956, Richard Usborne, the great scholar of P.G. Wodehouse, cursed the novel for inspiring fear in young boys. A present from his father, he read it shortly before starting prep school and, needless to say, understood why he’d been forced to take up boxing. With time he forgot how terrifying it was and, to his immense embarrassment, gave his own son a copy. Only when he reread it later in life did he come to the conclusion that its influence on teachers, parents, new boarders and writers ‘in all cases has been for the bad’.

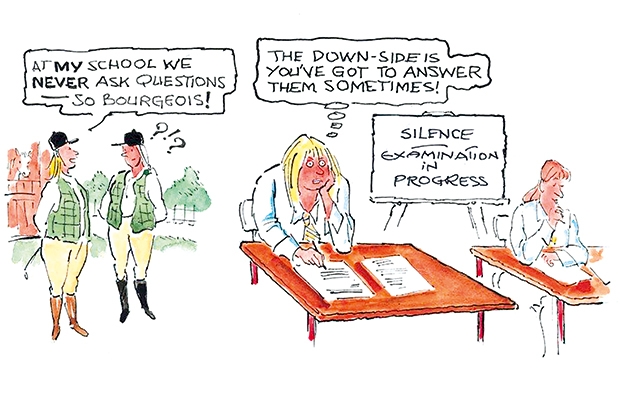

Lynn Barber’s early memoirs An Education (which inspired Nick Hornby’s screenplay of the same name) were published some years after I left school, but would no doubt have filled me with a similar sense of dread. At 16, you see, I joined the Lady Eleanor Holles School in Hampton, where Barber found herself surrounded by girls who owned ponies and never asked questions, which she found tolerable only because questions were ‘bourgeois’, and she wanted to be Existentialist, or at least French.

The school she described was dull and conformist, while the boys’ school next door, Hampton Grammar (now the independent Hampton School), was full of ‘little squirts’ who ‘turned into octupuses in the cinema dark, clamping damp tentacles to your breast’. I laughed when I read the book after leaving school, for parts of it rang true. My generation of LEH girls retained a (shamefully unfair) sense of superiority over the Hamptons, were as keen on ‘lax’ (lacrosse) as Barber recalls, and had Latin homework graded with an old-fashioned ‘alpha’ — or ‘beta plus plus’ if there were a few ‘howlers’. But so opinionated were we that, on a trip to the Houses of Parliament, an MP told us we were like lions unto Christians. If only Ms Barber had been there then.

I doubt we’d have been any less inquisitive if we had read her memoirs before starting. Call me biased, but headstrong girls are, I think, less prone than boys to turn a book into a self-perpetuating prophecy. Even at university, many boys were attracted to the idea of the Bullingdon Club because it meant ‘being a part of something’, and that something was what they had read about in the novels of Evelyn Waugh. There were Old Etonians who seemed convinced that they were re-enacting the antics of Bertie Wooster, and already had Wodehousian sobriquets when they came up. Few girls, by contrast, cared to consider themselves offspring of St Trinian’s (said to have been inspired by the former Perse School for Girls and St Mary’s School, Cambridge).

Looking back, the charades of boys so wedded to the literary traditions of their schools made life more colourful than it might have been in the drab noughties. Ridiculous, yes, but such fun!

If such a prospect does little to temper the often intimidating act of finding your school in books, there are at least some brilliant teachers to discover. The wonderful Miss Jean Brodie nurtured vivacious girls in her school, based on Gillespie High School in Edinburgh. Miss Pym, of Josephine Tey’s 1946 novel, Miss Pym Disposes, might well have been on the staff of Anstey Physical Training College, where Tey was a student. Though the college was dissolved into Birmingham City University in the 1970s, Radio 4 listeners voted Miss Pym a Literary Heroine of 2014. In life as in literature, it’s often the teacher who makes a more lasting impression than the school itself.

Unless, that is, the teacher is the school. James Hilton probably based Brookfield in his classic novel Goodbye, Mr Chips on his former school, The Leys in Cambridge. In the book, he describes how the wonderful Chips educated the darling rascals for around 40 years until he was Brookfield — the greatest compliment a school could have. Then there’s that terribly sad moment where Chips looks on as Speech Day turns into Ascot, and the headmaster rounds up prospective parents in London clubs to persuade them that Brookfield is the next big thing. And ‘since they couldn’t buy their way into Eton or Harrow, they greedily swallowed the bait’. The Leys is nothing like this today.

It’s more enjoyable — and less perilous — to read these books after leaving school than before starting it, but one can always allay a child’s fears and false expectations with the caveat that the stories are fictional, as many of them indeed are. But far better, I think, to listen to Mr Chips, who said that even great schools suffer vicissitudes, ‘dwindling almost to non-existence at one time, becoming almost illustrious at another’.

Pupils who visit Rugby or The Leys or LEH today would do well to tell themselves that these great schools were merely going through bad spells when the more horrid tales were set down.

Comments