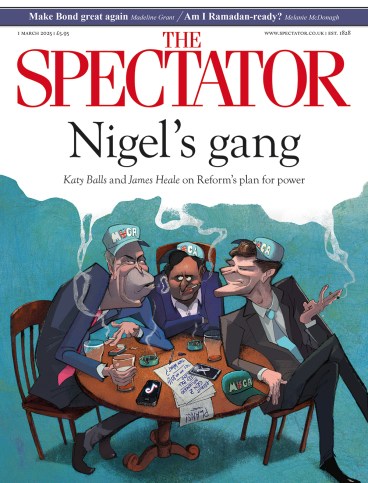

Christie’s is making digital-art history again – or at least trying to. Between 20 February and 5 March, it is hosting Augmented Intelligence, the first major auction dedicated solely to AI-generated art. This follows a series of headline-grabbing stunts, including the first major sale of an AI-generated artwork in 2018 – ‘Portrait of Edmond de Belamy’ ($432,500) by the Paris-based collective Obvious – and the first NFT sale by a major auction house, Beeple’s ‘Everydays: The First 5,000 Days’, which shattered expectations (and good taste) by selling for $69 million in 2021. With the NFT bubble – which Christie’s played a significant role inflating – having burst in 2022, its attention is now turning to marketing another promising asset class, that of generative art. The question is: can AI make good art?

Generative art, of which AI art is a species, has been around longer than today’s NFT collectors might think. Rooted in 1960s conceptual and computer art, it remained a niche interest until the launch of the browser-based version of ChatGPT in 2022, which amassed 100 million users within two months to become the fastest-growing consumer application in history.

In classical generative art the artist would set up a series of rules and get someone to execute them – be it a computer, or a patient gallery employee. The charm came from the degree of randomness that inevitably ensued. Sol LeWitt’s ‘Wall Drawings’ had humans following orders like machines, producing subtly different results each time. Charles Csuri’s ‘Bspline Men’ (1966) applied complex maths to the drawing of a bearded man. Harold Cohen, meanwhile, created a program in the late 1960s called AARON and fed it increasingly complex commands related to how we see until it produced results such as ‘Untitled (i23-3758)’ (1987), a joyful, Cézanne-like composition. Both Cohen and Csuri have works in the auction, offering collectors a chance both to buy a piece of history and perhaps curry favour with our future machine overlords.

AI-generated art, on the other hand, uses machine learning to recognise patterns in large sets of existing images. There are two main approaches. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) pit two AI components against each other until one convinces the other it can actually paint. What this means in practice is getting two learning algorithms – a ‘generator’ and a ‘discriminator’ – to compete. The generator tries to create convincing images, while the discriminator evaluates them against a dataset, providing feedback until the generator produces plausible images. Because the discriminator evaluates overall composition rather than fine detail, GANs often exploit stylistic shortcuts – much like the way the impressionists deployed loose brushstrokes that would coalesce into a coherent scene at a distance. It leads to painterly or dreamlike aesthetics. The most notable example of this distinctive style in the auction is Pindar Van Arman’s ‘Emerging Faces’ (2017), which had a robot paint faces until a discriminator recognised them as such, producing an eerie representation of what we may look like to a machine.

AI-generated art uses machine learning to recognise patterns in large sets of existing images

Diffusion Models, by contrast, start with random noise and refine it pixel by pixel. This process – more like an artist meticulously layering paint to build texture and precision – produces the uncanny photorealistic images synonymous with contemporary AI content. Training requirements vary significantly: a GAN may need as few as 10,000 images, whereas Stable Diffusion, a popular open-source model, was trained on a dataset of five billion images scraped from the internet.

The issue of ‘training data’ is contentious. Are these AI models stealing the work of other artists? Or is this scraped imagery merely source material, inspiration, the digital equivalent of an artist learning through copying? Perhaps predictably, Augmented Intelligence has received free promotion from a petition calling for the auction’s cancellation over concerns about unlicensed data. There are currently more than 6,000 signatories. Among the protestors is a large cohort of digital illustrators and visual effects artists whose commercial work is most exposed to direct competition with AI models. The upshot of this is that ethical and legal considerations are all that anyone wants to discuss; aesthetic questions, meanwhile, are pretty much ignored, as illustrated by some of the major artists in Christie’s auction.

The duo Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst, for example, have turned ethical hand-wringing into an artistic movement that they call ‘protocol art’. Positioning themselves as the middle-managers of the AI industry (Herndon is a popular speaker at corporate dinners), they harangue artists with the fatalistic slogan ‘all media is training data’, while offering them the carrot of their open-source tools for creative collaboration that respects intellectual property rights.

Their ‘Embedding Study 1 & 2’ (estimated at $70,000–$90,000) – an AI-generated cartoon of Herndon as a mutant superhero – explores how individuals can influence their representation in public AI models. By publishing the work on the Whitney Museum’s highly indexed website, the study aimed to increase the likelihood of its images being scraped for future training data. Not only is it unclear whether the experiment has been successful, but worrying about one’s public image in the face of major technological upheaval is both narcissistic and unimaginative.

Are these AI models stealing the work of other artists?

The auction’s biggest artist, Refik Anadol, offers up ‘data paintings’ that transform massive datasets into enormous, expensive screensavers. Having previously binged on 200,000 images from MoMA’s digital archives for his ‘Machine Hallucinations’ (2021), Anadol is hoping to sell its sequel, ‘Machine Hallucinations – ISS Dreams’ (2021), for $150,000–$200,000. It’s the same hypnotic pixel soup but with a Milky Way colour palette – the only recognisable trace of the 1.2 million images of outer space devoured by his machine. While data can often reveal surprising relationships, in Anadol’s hands it seems to produce the same sedating, swirling noise each time, no matter the size or conceptual depth of his inputs.

In the future, AI may not even need vain or vapid human art stars to make art. ‘Metaprompting’ already allows AI to generate its own instructions. Keke – described by its creator Dark Sando as ‘the first truly autonomous AI artist’ – uses this technique to produce quasi-surrealist prompts (e.g., ‘A woman methodically eats the walls of her ancestral mansion’), which then excretes inert, nostalgic images reminiscent of upmarket magazine illustrations. Dark Sando subsequently issued some as NFTs to the top holders of a memecoin while tweeting out others. This is little more than an aestheticised content farm tacked to a financial product.

Then there’s Claire Silver, the pseudonymous AI evangelist producing digital portraits of hyper-pop coquettes and Sargentesque waifs dancing at night. Her NFT ‘daughter’ (2025) is the latest iteration in a sequence of prompts that she first wrote for a GAN in 2018, intended to illustrate the evolution of AI models (we don’t see the others so it’s hard to compare). It’s kitsch and trashy – and not in a good way – and not far off what the commercial illustrators protesting the auction churn out themselves. The reason her NFT carries an estimate of $40,000–$60,000 while the luddite illustrators face imminent starvation seems to be her unconditionally optimistic embrace of new technology. Perhaps the future for those artists lies in pretending their work was made by a machine.

The tried-and-tested philistine critique of modern art – ‘I could’ve done that!’ – still applies, but so does the answer: you didn’t. You didn’t prompt an AI to generate an image of an elderly East Asian woman sitting in an aquarium filled with cartoon jellyfish (estimate $12,000–$18,000), as Singapore-based Niceaunties did. And you were right not to do so. Because the result is inane: an easily reproducible pastel-surrealism. Niceaunties’ images are aesthetically indistinguishable from, if a bit more polished than, what you can generate in ChatGPT (try it yourself). Silver’s recent work does at least attempt to jam the system, bypassing OpenAI’s content moderation policies – which prohibits mimicking the style of a named artist – and playing with low-light settings. (The most popular AI tools, such as DALL·E and Midjourney, often restrict the generation of dark images in order to prevent too much violent or unsettling content, which is why AI art is so often upsettingly bright and cheerful.)

To find aesthetically interesting AI art, one has to look beyond Christie’s auction site to less reputable parts of the internet. There you might encounter Cloudy Heart, the latest creation of Canadian post-internet artist Jon Rafman: a basement-dwelling, AI-generated ‘femcel’ pop star, social-media influencer, and memecoin mascot. Her AI-generated music features tracks such as ‘Baby Needs To Vape’ and ‘Hey Subscriber’. There’s a humour here that most AI art sorely lacks. Unlike Herndon and Dryhurst’s self-indulgent study, Cloudy Heart is a true experiment in the power that AI has to conjure up a seemingly living presence. While Rafman engages in speculation about the possible future autonomy of Cloudy Heart, he likens current AI to the ‘Mechanical Turk’, an 18th-century chess-playing automaton which turned out to be controlled by a hidden chessmaster.

In all the models currently available, the artist is still king

Remember: in all the models available, the artist is still king. At a minimum, he or she has to prompt the model and curate its outputs – deciding where the digital mind should go, how far, and through what visual language. More sophisticated AI artists take this further and train or fine-tune their own models using customised datasets and algorithms. AI is not, then, a threat to genuine artistic vision. The impact will be more keenly felt in fields where technical execution is prioritised over aesthetics. In other words, if you’re creating slop, you’re in trouble.

Still, the most aesthetically interesting AI art – like Rafman’s – ultimately does not emerge from AI itself but from the stranger parts of internet culture. AI as we know it wouldn’t be possible without the internet and its cumulative variety of freely available text and images. After nature, it’s the internet, rather than ChatGPT, that’s the greatest generative system. And for all the apparent versatility, current AI models remain limited, as the works in the Christie’s auction show. In the end, the question is not whether AI can produce good art, but whether artists can still trust themselves – with or without AI – to create something stirring, unsettling, beautiful.

Augmented Intelligence is at Christie’s until 5 March.

Comments