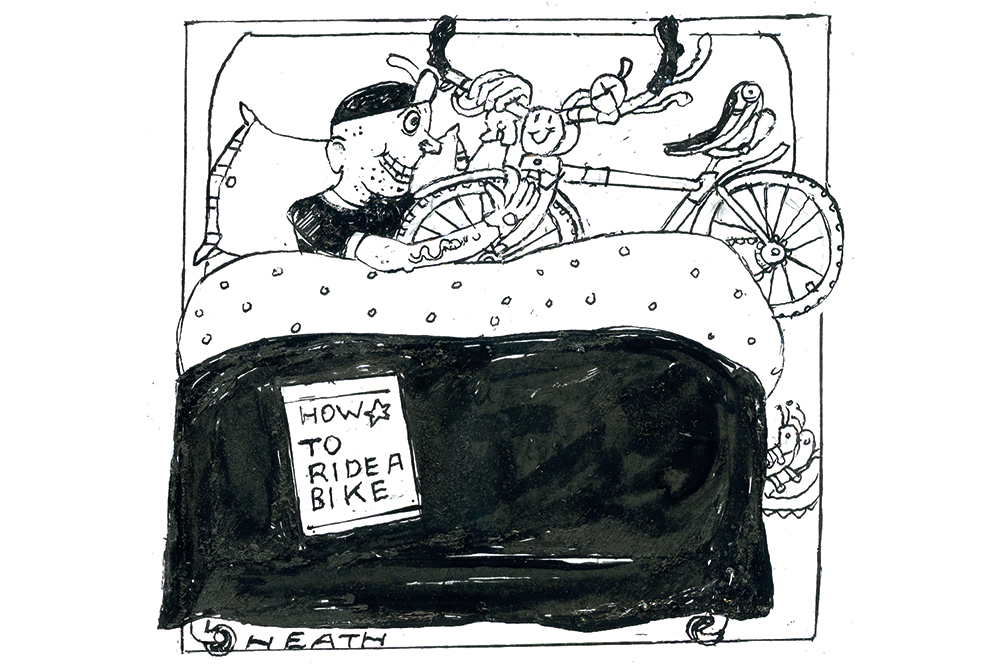

An impossible 45 years ago, I decided the moment had come to get back on my pushbike. I had long hated the way the motor car was taking over the world and wanted to play my part in changing this.

I also had a more selfish reason. After two years on the Fleet Street diet of lunchtime excess, I could already see my first heart attack was not far off. I was in my late twenties and getting almost no exercise. I knew of people in the newspaper business who did so little walking that the uppers of their shoes wore out before the soles did. Something had to be done.

In those days, bikes had not moved on since my childhood days, pedalling my heavy green Hercules over the Sussex Downs on summer afternoons. The brakes were as feeble, especially in the wet. The Sturmey-Archer three-speed gears were just the same.

For decades we fought for segregated cycle paths where no motor vehicle was allowed

The big difference was that there were millions more cars, and their drivers all hated me. I remember many things about those early days as a militant cyclist in the nation’s capital. I recall the morning my rattling second-hand bike was stolen by a middle-aged geezer in a tweed jacket, who managed to escape even though I was beating him round the head with a bag of dirty laundry at the time. I especially recall the struggle to get up Primrose Hill on my first two-wheeled journey home. The way in had been all downhill. But this was a serious gradient, and I was not going to give up and get off. As a result, I almost lost consciousness. The months of browsing and sluicing on the Daily Express had already begun to clog my cardiovascular system, and I swear I could feel actual globs of fat detaching themselves from the insides of my arteries as I heaved myself upwards. Until then I had just suspected this was important. Afterwards I knew.

I joined campaigns. I planned my routes to avoid the hatred of car-drivers and the indifference of lorries and buses. I thought it might make sense to ride across the middle of the Hyde Park Corner roundabout, rather than holding my breath and joining the rivers of steel which flowed around the junction. So it would have been, except that constables appeared from a tiny police station in the Wellington Arch and crossly ordered me off. The path (now an established bike route) was in those days reserved entirely for the royal family and their fleet of large cars.

Since then, most things about cycling have grown far better. Machines are lighter, brakes hugely more efficient, gears luxurious, reflective clothing and lights immeasurably improved (though I remain baffled by the widespread habit of wearing a Styrofoam bowl on your head). Cycle paths and tracks are everywhere. Quite a few drivers show cyclists courtesy and consideration.

But there are bad things too, not least the other cyclists who cut me up by undertaking me, or give us all a bad name by slicing through pedestrian crossings. But these are as nothing beside the menace of the electric bike and the e-scooter.

For decades we fought for segregated cycle paths where no motor vehicle was allowed, and we finally won. But no sooner had we done so than they began to be invaded by things which look like bicycles to the uninitiated but are in fact electric motorbikes. They are astonishingly heavy. Try to pick up one of these things as it lies on its side on the pavement (as they so often do). Typically, they weigh more than five stone (a normal pedal bike weighs about two). Officially limited to about 15mph, they can easily be tweaked to go much, much faster. This is technically illegal, but can you tell me who is checking? Then there are the ‘cargo bikes’ which can weigh about 12 stone and carry loads of about the same. If one of these hits you at any kind of speed, it will do you serious damage. So their arrival on cycle tracks undoes 40 years of campaigning to segregate muscle-powered, light, silent, clean cycles from engine-powered, whining, polluting, heavy vehicles.

May I just mention here that ‘e-bikes’ and their hideous cousins, e-scooters, are powered by batteries, which are charged by power stations. And much British power is imported from the Netherlands, which still uses fossil fuels to make some of its electricity. Thus, a million smug expressions on the faces of the users of such vehicles are completely unjustified. I have personal reasons to go further, having visited hideous mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, from which the metals for the batteries are grubbed by gaunt children on starvation pay. There is nothing ethical about these machines.

I have broken off relations with my local cycling lobby in Oxford, Cyclox, partly because they continue to treat e-bikes as the equivalent of proper bikes. Their attitude is common. The FT’s Henry Mance is typical of metropolitan trendies in praising them, gushing recently: ‘Have you ridden an electric bike? If not, you should probably stop reading this article and go find one. Hire one on the street. Borrow your neighbour’s. Steal one if you have to. Sat on the saddle, with the help of the motor, you will magically become half as old and twice as fit.’

Henry, you will absolutely not become twice as fit. Electric bikes cannot give you the exercise that proper muscle-powered machines provide. Claims are made that they offer some sort of fitness, but if I had ridden one of those things up Primrose Hill all those years ago, I doubt I would have discovered the vast and lasting health benefits that hard pedalling provides to anybody who wants it.

If people want to ride motorbikes, let them, once they’ve passed a severe test (as I have in fact done). But please don’t pretend these things have any of the benefits of a proper old-fashioned bicycle.

Watch Peter Hitchens debate Henry Mance on Spectator TV

Comments