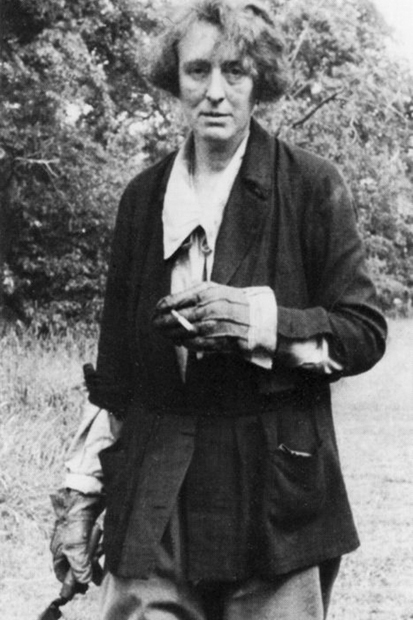

Here’s a book co-authored by one dead woman and one living one. Sarah Raven is the second wife of Adam Nicolson, grandson of Vita Sackville-West. In 1930 Vita bought Sissinghurst, the ruins of a great 16th-century house, and with her husband Harold Nicolson created the world-famous garden. Tell me the old, old story. Vita died in 1970, and in 1983 Adam’s mother published a similar volume, co-authored ‘by Vita Sackville-West and Philippa Nicolson’; and there are several other good books about the making of this garden.

So here is yet another well-illustrated hommage, from an intimate perspective, to Vita and to her gardening style. It is basically a compilation of large chunks from Vita’s gardening articles written for the Observer between 1946 and 1961. These were collected in several volumes, most of them reissued in recent years. The linking commentary by Sarah also incorporates extracts from other writers’ books about the garden.

The volume is given structure by grouping the articles according to theme or topic, and there is quite a lot of Sarah’s own autobiography included in passing, with accounts of her planting choices and preferences. (I am calling her Sarah because that is what she calls herself in publicity for Perch Hill in Sussex, where she runs a cookery and gardening business, a shop, and a considerable garden, as well as appearing on TV and writing books.) The dead gardener and the living one could hardly be more different as characters, though both are opinionated, and with a right to be so. Sarah is happy to be in the public eye and has a flair for marketing. Vita was complicated and reclusive — and, by the way, her love-life extended into old age, and was not restricted, as suggested here, to her thirties and forties; nor were her lovers largely ‘a series of beautiful young women writers’.

Never mind. It is Vita the plantswoman and garden visionary who concerns Sarah. Her assessment of Vita’s achievement is respectful but not subservient. Her clear-eyed confidence is contagious. She makes no criticism at all of Vita’s interior décor, but for the first time, reading about Sissinghurst here, I felt less than charmed by Vita’s fixation on the old, battered and time-worn. This had its roots in her childhood at Knole and her preoccupation with lineage. She liked grandeur, but from the past. Her velvets and brocades had to be faded and worn to shreds. If an object was bought new, it was faked-old. This romantic antiquarianism seems now a bit bizarre.

Sarah ends with a section on what she thinks is wrong with the garden as it is now. Following the death of Vita, it all began to change, until only a third of the plants in the garden today are ones that were there in Vita’s day. Decades of strong-minded and talented head gardeners have implemented planting ideas that never happened to cross Vita’s mind. They have brought in plants and new varieties of plants that she never knew, and excluded many she favoured. Her passion for growing climbing roses up and through trees has been more or less discontinued, for the good reason that the weight and density of the climbers tended to kill the trees. This was something, Sarah says, that Vita ‘got wrong’. For she did get things wrong. (I blame her for inculcating the widespread belief that peonies hate being transplanted. Honestly, they don’t mind a bit.)

All gardens must evolve, but Sarah is quite critical of the extent and nature of some of the changes. ‘There are strands of continuity and things that Vita would instantly recognise if she returned to walk through her garden’ but not, she thinks, enough. Too many of the plants she wrote about in her gardening columns are no longer there, ‘and there should be a return to more’. The garden is much tidier and more manicured than in Vita’s day. ‘Her overall philosophy of “Cram, cram, cram, every chink and cranny” has all but disappeared.’

Making the garden when they did, Vita and Harold had creative freedom. Writing about the centuries of detritus they cleared and the structures they demolished so as to design and plant, Sarah imagines ‘the archaeology that would have had to be undertaken nowadays’. So right. These days, English Heritage would be down on them like a ton of the rose-coloured bricks of Vita’s tower.

Comments