My daughter Leah was predicted a 5 in her English Literature exam. In the actual GCSE she sat at our local secondary in 2017, she got an 8, the equivalent of a starred A. I was delighted but not surprised. But while my daughter was able to prove her teacher wrong, what about those who this year will have to rely on predicted grades?

For Leah, such a situation would have been dreadful news. Two years after her GCSE English teacher under-predicted her, we found ourselves in the same situation again, but this time there was more than my daughter’s self-esteem to consider. Her academic future was at stake. In the autumn term of her final year at school, Leah was predicted ABB in her A levels. Great grades but not quite enough for her to get offers from the top universities where she was hoping to study.

Leah asked her teachers for higher predictions, pointing out that in her last exams she had achieved starred As in English, history and geography, the subjects she was now taking for A level.

Her teachers were unmoved. ‘There isn’t necessarily a correlation between GCSE and A level performance,’ one teacher told her. ‘We’ve met hundreds of Leahs before,’ said her head of year. ‘We know better than students what grades they’ll get. It’s part of our job.’

So I waded in. More than a dozen emails were exchanged between me and staff at my daughter’s school. It wasn’t a pleasant exchange. It was not said outright, of course, but it was heavily implied that I was a pushy, middle-class mum who was deluded about her daughter’s academic abilities.

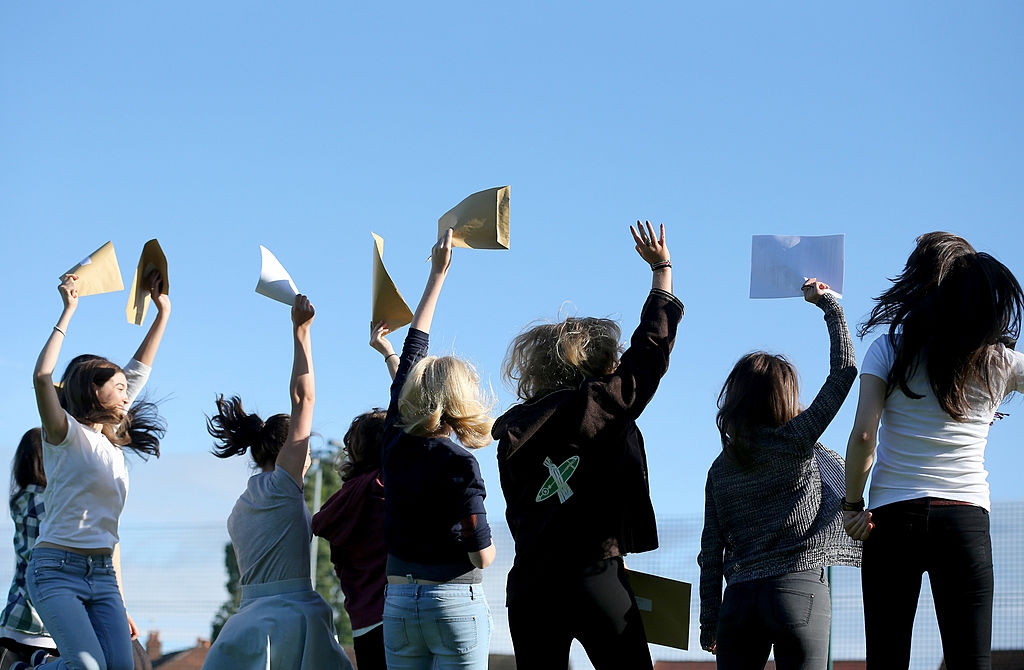

In the end, I wore the school down. Leah’s predictions were grudgingly raised to two starred As and an A. The result? She got an offer from Edinburgh university where she is now in her first year of a geography degree. And her actual A level results? Two starred As and an A.

I am appalled by the government’s plan to assess students this year because there is no question that teachers can get things wrong when it comes to predicting their students’ grades.

Luckily for Leah, she had me behind her. I am a graduate and a journalist. I’m not that easy to brush off. But what about working-class students whose parents have not been to university, who don’t always speak the kind of language teachers feel forced to listen to? Angela Rayner was right to tweet on Friday that working-class kids are twice as likely as their middle-class brothers and sisters to be predicted an E at A level.

The deputy Labour leader hopeful also noted that black pupils are under-predicted more than any other group: only 39 per cent of teachers’ estimations of their grades are correct, she said. It might jar violently with teachers’ self-image, but the truth is that bias can be unconscious too.

Meanwhile, it is no secret that private schools routinely over-predict the A level grades of the predominantly middle-class children who populate their classrooms. Their stakeholders, the parents paying the extortionate school fees, would not have it any other way. After Friday’s announcement, these students will now fare better than ever.

To arrive at their calculated grades, teachers will have to take ‘a range of evidence and data’ into account, including mock exam results and coursework. Hmm. Since her arrival at Edinburgh, Leah’s privately educated friends have told her openly that their teachers basically did their A level coursework for them. ‘It’s a bit like piracy,’ said one girl. ‘Teachers know it’s not right. We know it’s not right. But it’s rife.’

Working-class and ethnic minority students, already under-represented at our elite universities, will now be more disadvantaged than ever. And they and their parents will be rightly worried. I do not doubt the government’s plan is well-intentioned. But it will simply lead to privilege buying more privilege.

Comments