Readers of this journal will be shocked at the death of Laura Gascoigne, the brilliant chief art critic at 22 Old Queen Street for five years (2020-24), in succession to Martin Gayford. She contributed over 200 articles to The Spectator between 2001 and 2024 that would well deserve being reprinted in a compendium of art criticism.

She wrote widely, with care and discrimination, for Apollo, the Tablet, and the Daily Telegraph among other papers. First and foremost, she regarded herself as a writer who loved stories and loved the telling of them, but who also happened to know a lot about art. You could see her talent for drawing in the reader in her final piece for The Spectator, a review of the Courtauld exhibition of Monet’s 21 London views, ‘Fog, tea and full English breakfasts‘ (9 October 2024). The opening is a masterclass:

For the maids on the top floors of the Savoy, everything was in turmoil. The 6th had been commandeered by wounded Boer War officers, and since February 1900 a suite of rooms on the 5th had been taken over by a French painter, who was using one as a studio. The officers were nice enough, but the Frenchman spoke almost no English and you could smell the turps down the corridor. Whatever was the management thinking?

What the management was thinking was that the Frenchman was an internationally famous artist and the Thames views that he was painting from his window would serve as great publicity for the capital’s most expensive hotel, which in 1900 advertised ‘a panorama from Battersea to the Tower Bridge… in all weathers, in sunshine or in rain or in the fog loved by Mr Whistler, a thing of beauty’.

The organisers had booked the Savoy for the press launch. I remember Laura there amid the canapé-sized croissants and tulip glasses filled with yoghurt. That was a little over a year ago. Thereafter her familiar presence at press views, often sitting cross-legged on the floor, notebook in hand, was no longer to be seen.

In March this year she wrote, ‘I have to confess I’m not missing reviewing. I’ve been using the opportunity to catch up on reading, consuming classic novels by the score… And as soon as it is warmer I’ll be gardening. Sometimes a break, for whatever reason, is welcome.’ She also much enjoyed painting.

She had occasional pieces in the satirical art paper the Jackdaw that, while never waspish, gently passed judgment on the contemporary art world that she had come to know so well. Her 2017 novel The Horse’s Arse, about art fakes and dodgy dealers, would have delighted Joseph Addison and Richard Steele.

Laura Gascoigne’s father, Colonel Esmond Warner (1907-82), had been stationed in Apulia after the invasion of Italy. Her mother, Emilia Terzulli, was working as an interpreter for the Allies when the Germans bombed Bari in 1943, and Warner came to her rescue. Married in 1944, the couple lived in London after the war where their first daughter was born before moving to Egypt.

Laura was just two years old when King Farouk was overthrown and life in Cairo, the smart parties for the British set, ended. The family moved across Europe to Brussels where Esmond managed a branch of WH Smith. The two sisters attended a convent school, learning Flemish – that Laura promptly forgot – and, by her own admission, bad French. (Her elder sister, the historian Dame Marina Warner, recalled their childhood in her 2021 memoir Inventory of a Life Mislaid.) Perhaps it was here that Laura developed her tinkling voice and sense of innocent mischief.

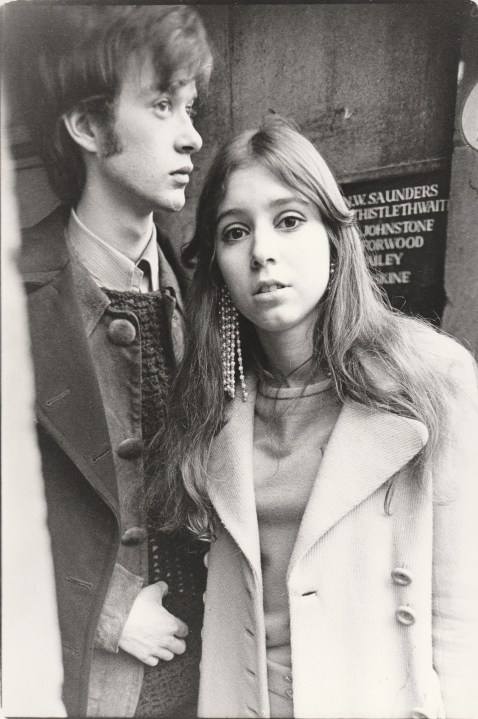

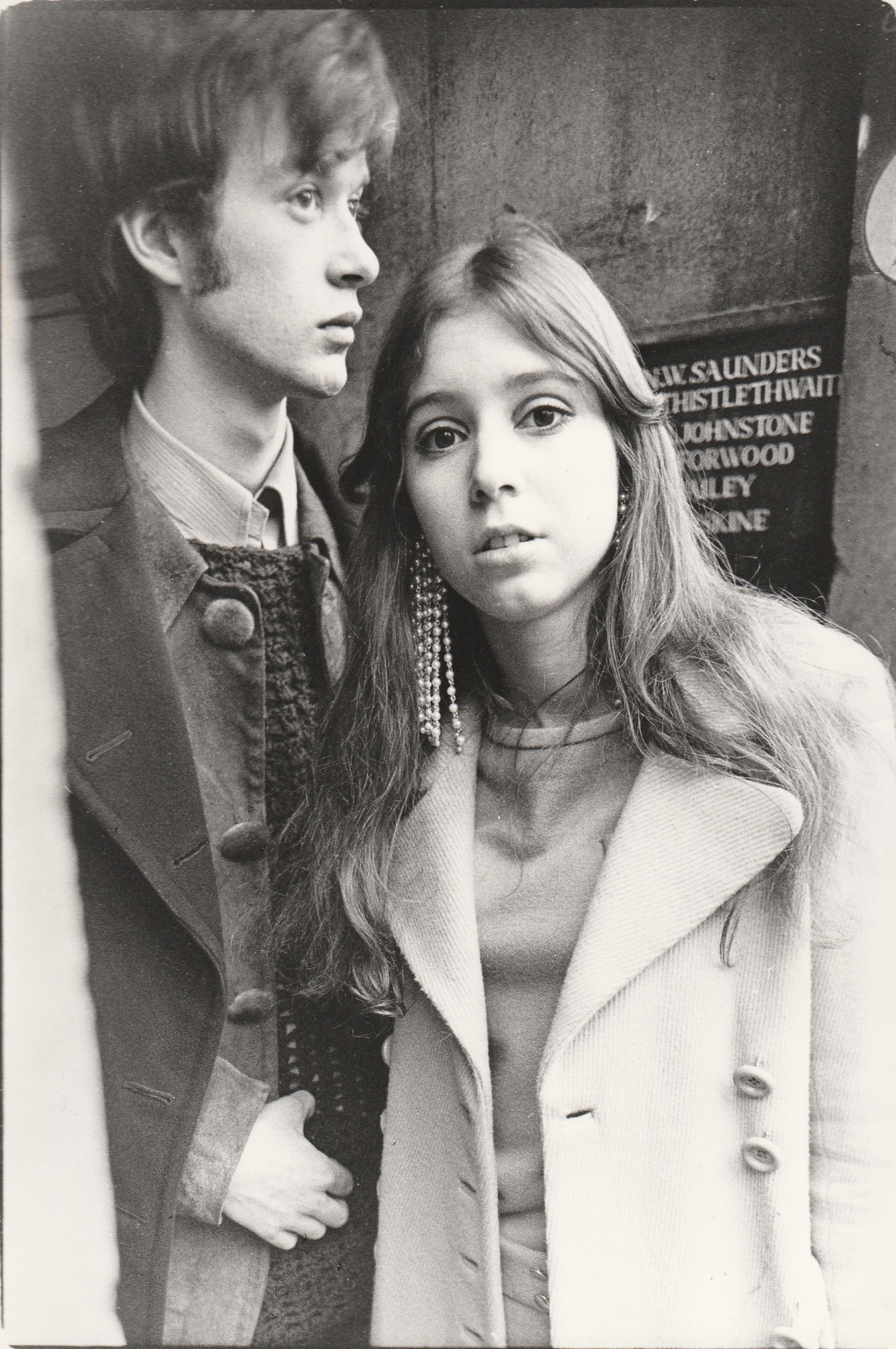

She read Greats at Somerville, Oxford, and acted. She played Diana in a student production of All’s Well that Ends Well with Harriet Walter as her mother, and appeared alongside the Prince of Wales in one of his sketches for the Dryden Players. In London she set up shop at the end of King’s Road. There she met the pianist and composer Brian Gascoigne, whom she married in 1977 and by whom she had two sons.

She was a Catholic and worshipped regularly at St Dominic’s Kentish Town. A faith that would quietly reveal itself in her annual Spectator Christmas essay, in which she would meticulously dissect a Nativity scene. Take her close reading of Hieronymus Bosch’s ‘Adoration of the Magi’ (c.1494) from 2023, which deserves quoting from at length:

Standing inside the entrance to the stable is a curious figure in a bizarre headdress wearing an off-the-shoulder red cloak and very little else. His face and neck are tanned but the rest of his body is deathly pale, and he has an oozing wound on his right leg encased like a reliquary in a crystal sheath. Between his legs a bell hangs on a ribbon embroidered with frogs, and in his left hand he holds a helmet resembling a papal tiara… The tiara is decorated with a frieze of little trolls tormenting some herons – one of which bites back – while his own headdress is wreathed in a crown of thorns and topped by a crystal tube in which the thorns are blooming…

Who is this pantomime villain with his consigliere, a horrid old man with a purple face and bright red nose? He is the Antichrist, the false Messiah sent to mislead the Jews in punishment for their failure to recognise the true one, and he is indulging in a bit of Christological cosplay in his red cloak and crown of thorns mimicking the Passion… Even when heralding the birth of the Saviour, Bosch can’t resist sending shivers down the spine…

The miracle taking place outside this stable hasn’t permeated to the wider world. On the left wing, behind the figure of Joseph, a Hammer-Horror gothic arch topped by a hand-standing frog leads to a field where ribald peasants dance rambunctiously. From the posture of one peasant and his partner’s reaction, you’d swear he was exposing himself (if so, he must be the only flasher in an altarpiece). In the centre, behind the stable’s pitched roof, a monkey riding a mule is pulled towards an inn identified as a brothel by the swan on its banner. Christ may be born in Bethlehem, but life goes on.

Her learning (always worn lightly) was peerless. And she was one of the few critics who really looked. On one of our last press visits together in early 2024, to Naples, ahead of the National Gallery exhibition of Caravaggio’s final painting, she found an altarpiece in Santa Maria della Sanita that might well have been Caravaggio’s actual final painting, finished later by a pupil. None of us had searched it out. Assured, attentive and assiduous to the last.

Read all of Laura Gascoigne’s articles for The Spectator here and here.

Comments