‘What is he talking about?’ Marine Baudrillard would sigh whenever she read her husband’s work. Anyone who has studied for an arts or a social-science degree over the past few decades will know what irked her. A sociologist-cum-philosopher’s prose is to thought what mud is to a windscreen. ‘There is no more hope for meaning,’ Jean Baudrillard wrote with unconscious exactitude in Simulacra and Simulation. ‘This is a good thing: meaning is mortal. Appearances, though, are immortal, invulnerable to nihilism. This is where seduction begins.’ In their admirably brief critical biography, Emmanuelle Fantin and Brian Nicol praise Baudrillard’s writing for its ‘enigmatic verve’. One might as well commend Bruckner’s 8th for its enervating brevity.

Only a fool would claim that the existence of untruths means there is no such thing as the truth

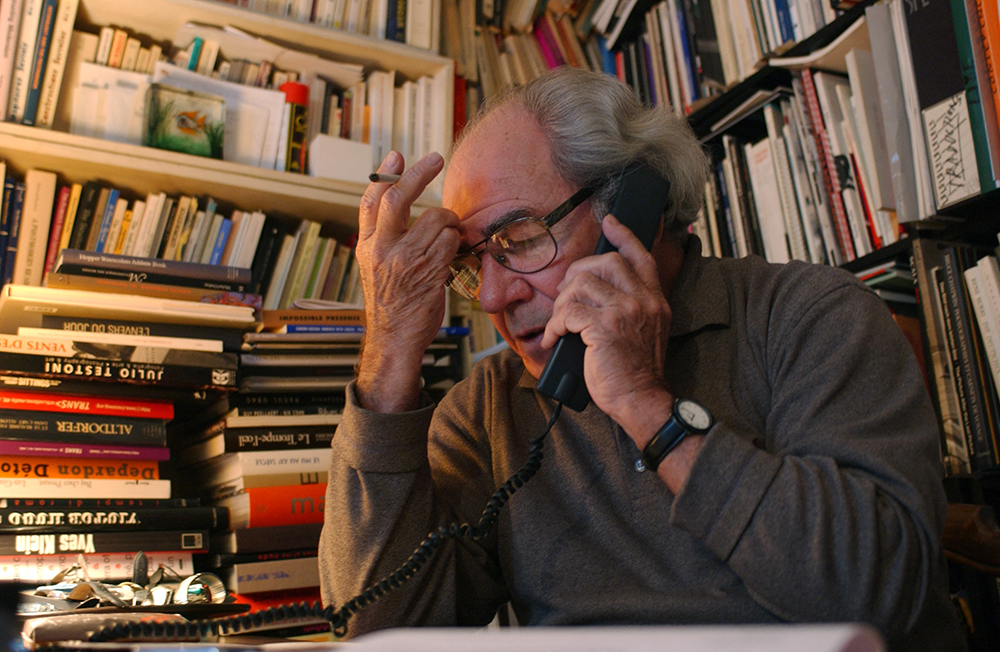

Baudrillard himself never lacked energy. Though he was 39 when his first book was published, he soon made up for lost time. Fantin and Nicol’s bibliography lists more than 40 titles he wrote. Add in the eight or nine book-length interviews he gave and you have the sociologist as Stakhanovite. Yet they quote Marine as saying: ‘I never saw him work hard.’ We are told more than once that he ‘found writing easy’, and that his work required ‘little editing or revision’. But no real writer can think like that. As Thomas Mann said, a writer is someone ‘who finds writing harder than other people do’.

What did Baudrillard imagine he was saying? His abiding notion, swiped from Walter Benjamin’s essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ and Daniel Boorstin’s early 1960s bestseller The Image, and then sifted over with the patter of post-structuralist linguistics, was that the mass media of the modern era don’t so much represent the real world as replace it. Thanks to the sheer spread of imagery, there are now more signifiers (images) than signifieds (concepts). Marshall McLuhan had been wrong about the medium being the message. There aren’t any messages because the medium does nothing but talk to and about itself. Baudrillard christened this arena of despair the ‘simulacrum’.

In the simulacrum, human action is the stuff of fantasy. In May 1968, when the streets of Paris were filled with student hotheads and situationist agitators, Baudrillard dismissed their antics as ideological idiocy – the posturings of ‘normative’ Marxists. It is important to be clear here. Baudrillard wasn’t saying that the radicals’ ideas were impractical. He was saying that they were impracticable – because there was no world for them to act upon. You could dream of intervening all you liked, but the signifiers that surround you, the images that are your only habitat, can no more be altered than your pupillary distance.

Baudrillard hit peak absurdity in 1991 when he published three essays in –Libération (translated in the Guardian) which argued that the Gulf War would never take place, that it wasn’t taking place, and then, after the war was over, that it hadn’t really taken place. Like the expedition to Mars in Peter Hyams’s conspiracy thriller Capricorn One, the whole thing was a phony, a put-up job, the latest fabulation of the simulacrum. Now anyone who remembers the footage of the aerial bombing of Iraq can surely also remember wondering whether what they were watching was really happening. But such questions about the veracity of FX-like visuals (this was pretty much the first occasion TV viewers were made privy to high-end, real-time imagery of war) didn’t mean one doubted that there was a war on in which real soldiers and real civilians were being killed. To be sure, that war, those deaths, were reported more accurately in some places than in others. But only a fool would claim that the existence of untruths means there is no such thing as the truth. And only a charlatan would argue that because the truth is hard to ascertain we should stop trying to do so.

If Baudrillard’s ideas sound familiar it’s not just because they were given dramatic form by the Wachowski brothers in their Matrix movies. Worries about the slippery difference between appearance and reality are older than Plato – as old as the Buddha. What is new in Baudrillard is his acceptance of, and his gleeful obeisance before, the idea of illusion. He doesn’t want to draw back the curtain in the hope of proving we’ve been suckered. He just wants us to revel in the con. Philosophy, sociology, theory – these are small things in the big wide world. But once they give up their claim to moral seriousness, once they abandon the belief that at least parts of reality are susceptible to human apprehension, they are finished. If you’ve ever wondered what la trahison des clercs looks like, it looks like this.

Comments