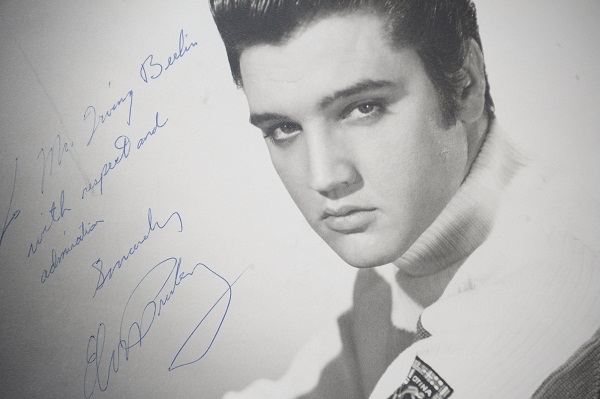

Shall We Gather At The River is a book of unfortunate endings — the stories of nine suicides hang from a plot-line that tells of a freak flood in the small Irish town of Murn. Fittingly for a book preoccupied with endings, we begin at the end: our hero, Enoch O’Reilly, is sitting in his father’s basement and staring down the barrel of a gun. The narrative then leaps backwards by 28 years to give us Enoch as a child in that same basement, stumbling upon his father’s old radio equipment and finding, in that forbidden room, a radio that channels an Old Testament sermon delivered in such rousing style that Enoch feels compelled by the power of Elvis Presley (who appears to Enoch in a dream that night) to ‘steal the preacher’s fire’. Expulsion from the seminary for atheism sees him return to Murn a self-styled ‘radiovangelist’ and Elvis impersonator.

Enoch’s strange obsession with Elvis is left refreshingly detached from any tired thematic hand-wringing over the nature of celebrity. At most it seems as though Enoch is undecided on whether he wants to impersonate Elvis or whether he wants to impersonate a priest — and although you’d think that there might be some old-hat point about ‘inauthenticity’ in the works, there seems instead just a gentle note on the bizarre divergences even minor indecisions can sometimes take.

If this is a novel about ‘how the young Enoch O’Reilly was possessed by the voice of the rambling man he would become’, then it’s also a novel about fate and family. Murphy is sensitive to ways in which religious language fits neatly with familial ill-fatedness; but then Christianity explicitly provides us with a tale of a father condemning his son, and of that son accepting his fate. Murphy’s trick is to turn Enoch’s doom into an absurdly self-imposed doom – after all, Enoch doesn’t even believe in God.

The river, and the story of the flood, is both biblical damnation and overwhelming psychic damage. Enoch’s father describes its flow as ‘the sound of thought itself’; it ‘erodes the stuff of sanity through repetition, recurring thought patterns or cruel loops like phrases murmured in a fever’. The river as trauma cuts ‘the rut’ and makes way for other ‘currents generated by the mind to follow these treacherous paths of habit’. The repetitive cycle of trauma and prophecy pose questions about self-awareness — in an interview transcript the novel’s psychiatrist, Charles Stafford, wonders whether one part of the mind ‘knows what is before us, even as our waking consciousness cannot or will not acknowledge portents of the catastrophes ahead’.

Perhaps the thing that stops this from being a dull novel about the horrors of fate is that it is funny. Ornate, even grotesque, comic episodes are a significant part of its charm. Enoch’s Revival Hour Abortion Special is noteworthy for ‘the… frenzy into which Enoch whips himself as he holds aloft a Cabbage Patch Doll and violates it with a coat-hanger while novelty shop blood spurts from its eyes’.

Murphy moves into and out of various characters’ voices with ease and grace. Alice reacts to news of her mother’s terminal illness with well-crafted suppression (‘her mother’s test results were worse than bad, inoperable. And all Alice could think was what a strange word that is, inoperable’); downtrodden Isaac can’t quite recall hitting his wife (‘I stuck my hands in my pockets to keep from striking you back but then something happened and you were on the floor with a bloody lip’). Both stories end in suicide, but both are wonderful portrayals of how we try to re-narrate ourselves and our lives, even if our new stories don’t last long enough.

The novel circles suicide unrelentingly, but its obsession with death is subtle. Although occasionally its moral seems to be that the explicable can become strange and the strange explicable — as though strangeness is found in a description and not an event — we are left with the weirdly pagan death of Enoch, and the observation that ‘there is no answer, only multiple signals inhabiting a single channel’. ‘Everything in the earth shall die’, we are told, but no, says Charles, ‘I can’t say for certain why it happens.’

Peter Murphy, Shall We Gather At The River is published by Faber & Faber.

Comments