The leak of a draft Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade has sparked a furious reaction in Britain. Yet for all the backlash in British political circles, the reality is that the proposed shake-up of abortion laws in the United States doesn’t really matter here. Our nominally conservative-leaning parliament just voted to make abortion easier, and the issue is nowhere near as salient for the British right as it is in the US. Those who are furiously denouncing the ruling are wading into an issue that will have little to no impact on their own lives.

Yet there is something significant for Brits to take from this furious debate: we’re lucky that we live under the rule of law rather than the rule of lawyers. How much longer will this be the case? Across the Western world, activists, lawyers, and politicians have worked assiduously to shift intensely controversial and inherently political issues from the realm of politics into the realm of law and human rights, where inconvenient obstacles such as debate and democratic process are no longer present. The abortion row shows why doing so is not a wise approach.

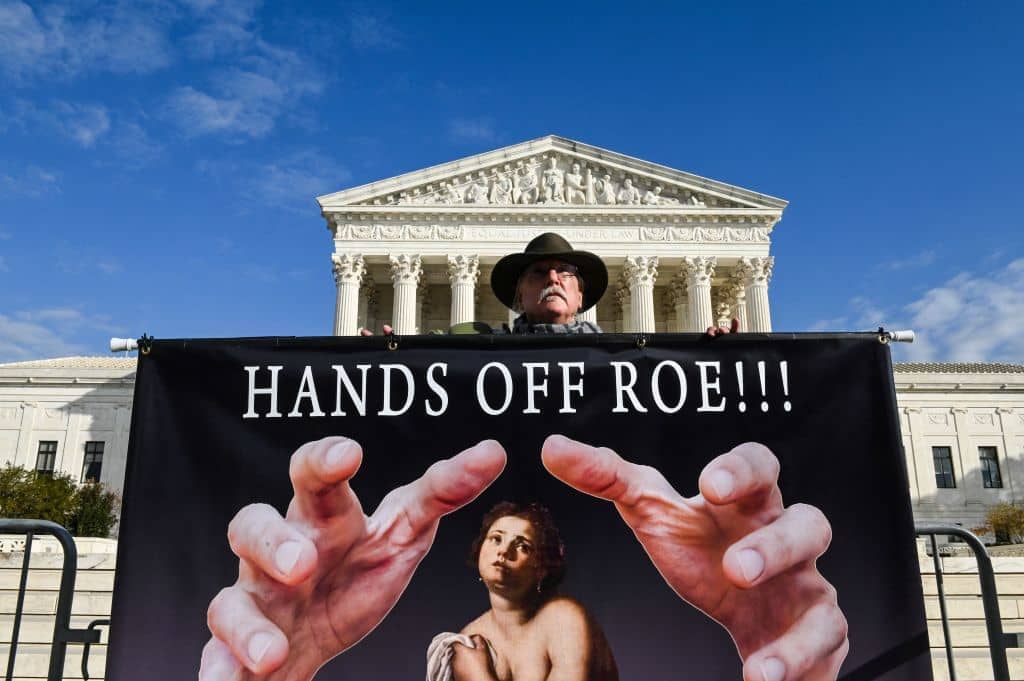

We should ignore the backlash to this leaked ruling

It’s hardly surprising that liberal coalitions founded on the basis of disliking existing social structures should strike on this tactic eventually. Using the law to achieve political ends means you don’t need to persuade the public to come along with you. All you need to do is present a sufficiently sympathetic court with an argument that invites them to go along with what they want to do anyway. Once pushed into this space, political issues become instead matters for judges and lawyers, with all discussion framed in terms of technical compliance. Legislators may complain, but know their hands are bound; what the courts have done let no man undo.

Or at least, that’s the theory. The anger in response to the draft decision seems to come less from its contents than the discovery that this process is not irreversible. Activists are not complaining about subtleties of legal argument. They are complaining about the existence of the decision itself.

Roe v. Wade, in the view of the dissenting justices at the time of the decision, was an ‘exercise of raw judicial power’. The draft decision agrees with this claim. It insists that the matter should return to democratic discussion instead of being the subject of constant lawfare. In the view of Democratic senator Elizabeth Warren, this makes the Supreme Court an ‘extremist’ body that wishes to ‘impose its far-right, unpopular views on the entire country’.

Really? From London, this looks like a decision stating precisely the opposite; that the centre should not impose views upon the entire country, and that each state should be left to decide for itself through democratic debate and discussion where the boundaries lie. But then again, that assumes that courts are meant to interpret and apply the law.

The fact that even proposing the overturning of an earlier Supreme Court decision can generate such a toxic reaction demonstrates the limitation of the depoliticisation of rights. What we see all too clearly is that Roe v. Wade, for all its pros and cons, simply shifted the locus of political sentiment towards the courts, and with it a view that decisions hold legitimacy only when handed down by a bench packed with your people. This in itself is a good reason to support the draft decision that has emerged this week.

Objections to the leak are almost exclusively being framed in terms of consequence, rather than in terms of law. This points to a worldview where judges are viewed not as impartial interpreters but as de facto legislators. This is not a good advert for the American political system: if decisions depend only upon the party composition of the court, it makes a mockery of the clear and predictable implementation of law.

So we should ignore the backlash to this leaked ruling: the Supreme Court returning matters of politics to the realm of politics is not an assault on American democracy. Rather it’s a statement of faith in its ability to handle complex moral arguments, and an attempt to preserve what little faith in its ability to act impartially still exists. Brits should take note – and consider whether it’s time to start dismantling our own edifices of depoliticised rights.

Comments