Getting the words ‘impressionism’ and ‘modern art’ into one exhibition title is a stroke of marketing genius on the part of the National Gallery, but is it too much for a single blockbuster? Symbolism, cloisonnisme, pointillism, expressionism, cubism, abstraction: if impressionism was a watershed in modern art, the streams that flowed from it were many and various.

By setting a time frame of 1886 to 1914 – from the last impressionist exhibition to the first world war – After Impressionism: Inventing Modern Art narrows its options only to widen them by expanding its focus beyond Paris to Brussels, Barcelona, Vienna and Berlin. In the closing decades of the 19th century, groups of young avant-garde artists in these happening European capitals (dozy old London is off the map) ganged together in exhibiting societies to challenge the academic status quo. Enterprising and outward-looking, they were not just membership societies; they invited foreign artists to exhibit. Thus at a time when Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh were only just becoming famous in France, examples of their work were being introduced to audiences across Europe. It was at an exhibition of Les XX in Brussels that Van Gogh made his only sale in 1890.

It was at an exhibition of Les XX in Brussels that Van Gogh made his only sale in 1890

The story starts in a gallery shared by the three great pioneers of post-impressionism, with Maurice Denis’s 1900 group portrait of their young disciples, the Nabis, gathered in admiration of a Cézanne still life. But none of the above seem to have had much influence on Brussels, where it was pointillism that went viral. After Les XX showed Seurat’s ‘A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of la Grande Jatte’ in 1887, the Belgian avant-garde, led by Théo van Rysselberghe, broke out in dots. None of them worked Seurat’s magic with colour (the Italian divisionists made a better stab at it) and their embroideries on the theme are slavishly dull; it’s left to James Ensor’s daffy ‘Astonishment of the Mask Wouse’ (1889) and George Minne’s etiolated ‘Kneeling Youth of the Fountain’ (1898) to defend the Belgians’ claim to originality. Like Ensor, Minne was a one-off. The other sculptors in the show are all in thrall to Rodin, whose massive Balzac looms over the entrance, but Minne took sculpture in a new direction, anticipating Giacometti and inspiring Schiele.

The Nabis’ influence is visible in Barcelona in Hermen Anglada Camarasa’s lusciously patterned ‘The White Peacock’ (1904), painted in juicy oils that look good enough to eat. The young Picasso, meanwhile, tries different styles for size, giving the cloisonnist treatment to the ‘Absinthe Drinker’ on one side of a 1901 canvas and the impressionist treatment to the ‘Woman in the Loge’ on the other. Interestingly, Ramon Casas’s ‘The Automobile’ (c.1900), showing a woman driver at the wheel of his Renault, is one of only two images – with Toulouse-Lautrec’s ‘Tristan Bernard au Vélodrome’ (1895) – of a modern subject. Before the Italian futurists, European modernists were content to challenge traditionalists on their own turf.

The mood feels different in Vienna and Berlin, where the Secessions boasted their own buildings and the patrons were richer. In the Vienna section, you seem to breathe a more perfumed air: the two large paintings by Klimt are as much fashion plates as portraits – he and his partner Emilie Flöge designed the diaphanous dress Hermine Gallia is wearing. There’s nothing here by Egon Schiele to lower the tone. Berlin, thanks to the presence of Munch in the early 1890s, is funkier. The Norwegian’s shockingly modern treatment of subjects like ‘Death Bed’ (1895) closed his debut show in the city after a week, but the German Max Slevogt held his own with ‘Danae’ (1895) – a money shot of Zeus’s squeeze in post-coital slumber while gold coins rain from the ceiling to be collected by her maid – which managed to get rejected by the Berlin Secession.

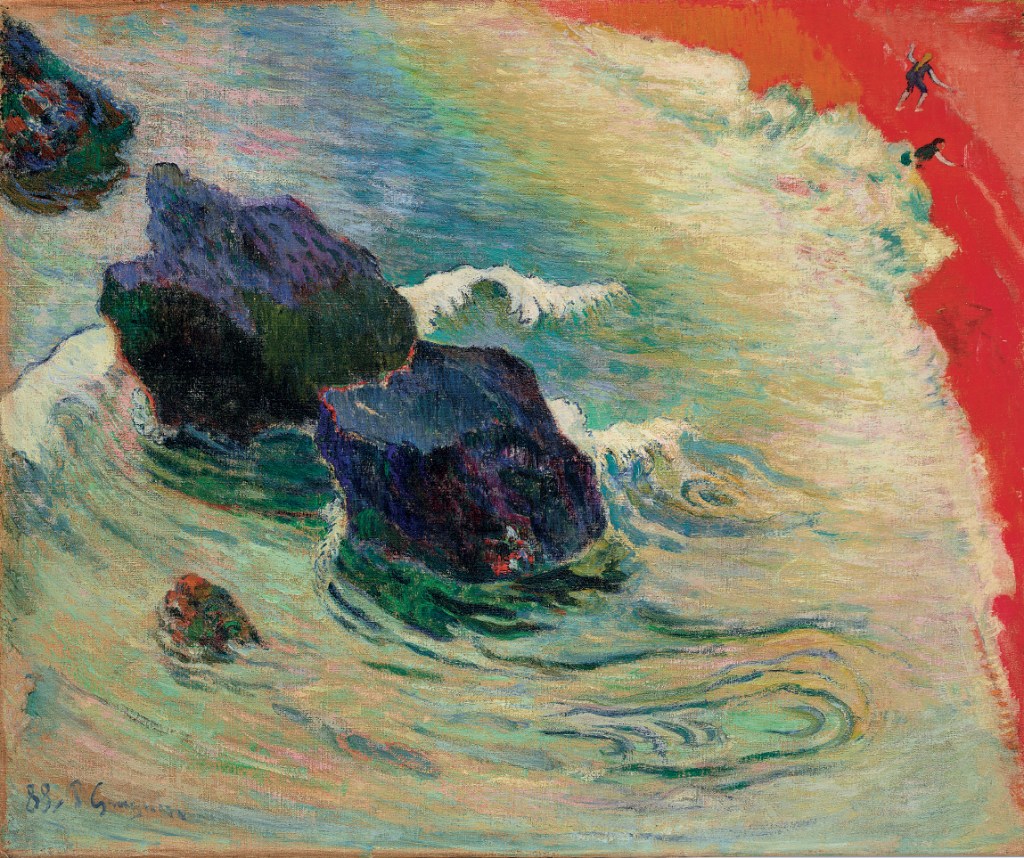

Egon Schiele is not the only glaring omission from this show. Ludwig Kirchner is missing from the members of Die Brücke – the Dresden-based group arguably most influenced by French post-impressionism – crammed into an overflow room of oddments with Paula Modersohn-Becker and Henri Douanier Rousseau. But it would be grouchy to grumble about an exhibition so rich in rarely seen masterpieces, many of them loans from private collections. Don’t miss Van Gogh’s ‘Houses in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer’ (1888), with its bright yellow sky shimmering in the heat haze from the cottage chimneys; Gauguin’s ‘The Wave’ (1888), with its bird’s-eye view of bathers on a Breton beach scurrying away from a Hokusai breaker (see below); and André Derain’s monumental ‘La Danse’ (1906), whose sequestration in a private collection allowed his fellow Fauve Matisse to take all the credit for this compositional idea with his more famous version painted four years later.

If this show’s international taster menu leaves you hungry for more, that’s the mark of an appetising meal.

Comments