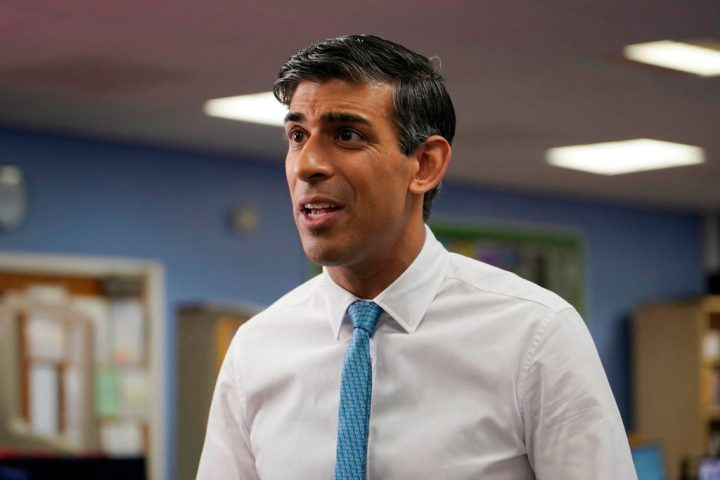

Rishi Sunak is a big fan of a ‘crack down’. He has previously vowed to crack down on migration, anti-social behaviour and climate protests. ‘Rip off’ university courses that ‘don’t offer the prospect of a decent job at the end of it’ are the PM’s latest target. But Sunak’s tough talk and aggressive rhetoric smacks of over-compensating for any lack of real detail.

Politicians love to poke fun at ‘Mickey Mouse’ degrees, but rarely define what they actually mean. In an interview on Good Morning Britain, higher education minister Robert Halfon couldn’t name a single degree, salary threshold or ‘good job’ against which the criteria for a ‘Mickey Mouse’ degree could be set.

It’s easier to sardonically mock fake degrees like puppetry at Arsehampton Former Polytenic than it is to give real policy content or evidence. Universities already face fines from the Office for Students (OFS) if they do not meet targets for ensuring students complete courses and are in graduate jobs 15 months after university. Meanwhile, the use of graduate salary data as the sole metric for judging quality is reductive and unhelpful.

Here’s the thing no one ever really wants to admit for risk of sounding elitist: the quality of the university matters far more than the course. Studying law – a more vocational, supposedly ‘employable’ degree – at the University of Wolverhampton is not necessarily a ‘better’ idea than studying philosophy at Durham: the former has a progression rate of only 56 per cent. According to OFS, only 35 per cent of graduates who study Computing at London Metropolitan University ‘proceed’ to a positive graduate destination, and yet you rarely hear Computing being called a ‘Mickey Mouse’ degree.

Instead, ‘rip off’ degrees become thinly-veiled insults towards non-STEM subjects. Yet graduates of social sciences, humanities and arts make up 58 per cent of FTSE executives. Meanwhile, one survey by the British Academy found that their employment rates and earnings ten years after graduation were almost identical to those of STEM graduates. Creative industries also employ 2.3 million people and generate £108 billion a year.

Perhaps studying English at Lincoln University may not be as financially lucrative later down the line as studying engineering at Imperial, but not everything has to be about economic value. What about learning creativity, critical thinking, empathy, communication? As Oscar Wilde said, a cynic is someone who ‘knows the price of everything but the value of nothing’.

The discussion around university courses also often feels disingenuous because politicians don’t practise what they preach. I bet that almost ever single politician who supports this policy went to university themselves, and, if they have kids, would want them to go to university too. It’s always that other kids shouldn’t go to university. What are the chances that Rishi Sunak will push his daughters to do an apprenticeship when the time comes?

Of course, people can and will say that most degrees are still not worth the student loan repayments. Young people are aware of the debt burden and the graduate tax they take on to experience something their elders got for free. Yet they still apply in record numbers because the reality is a lack of viable alternatives.

The vast majority of well-paid jobs (in fact, any job) require a degree, and apprenticeships are few and far between: often highly competitive, concentrated in the capital (with the associated cost of living) and pay below minimum wage. It’s no surprise therefore that in 2020/21, only five per cent of people on a degree-level apprenticeship came from lower income areas.

Part of the problem is that our one-size-fits-all university system means we continue to disagree over what the purpose of university is. Is it employment training, or education and a love of learning for its own sake? If it’s the former, then we need to think about how to ensure universities prepare people for the workplace: for example, increasing the number of courses with an industrial placement year. If it’s the latter, then we need to celebrate intellectual curiosity and offer aspirational alternatives to those who aren’t suited to academia. Neither, however, would benefit from simply taking a sledgehammer to certain courses.

Rather than criticising ‘rip off’ degrees, why doesn’t Rishi Sunak instead focus on ‘rip off’ rental hikes, mortgage costs, energy prices, childcare demands, crushing tax rates, wage stagnation, or any of the other burdens facing graduates?

Sunak is right that graduates have been ‘sold a false dream’, but not by universities. Most graduates have been brought up to believe that if you work hard enough, you can own a home, be stable enough to start a family, and at least keep half of every pound you earn. Now this is no longer the case, who can blame young people for wanting to delay joining the job market for a couple of years?

Comments