In Tamil Nadu we found that we were exotic. Although there were some other western tourists around, in most of the places the great majority of visitors were Indian. My wife Josephine, who is tall and fair-haired, appeared to be particularly unusual-looking. As we walked around a temple, she would frequently be invited to pose for photographs with groups of sari-clad women.

Exoticism is one of those qualities that exists in the eye of the beholder. To western Europeans, this area at the tip of the Indian triangle has been the epitome of that quality for more than 2,000 years. The Romans came here, and some even settled — the Apostle Thomas for one. We saw his tomb and basilica in Chennai. Such was the classical appetite for pepper and the other spices that grow in abundance in this region that Pliny the Elder complained that all the gold in the world was draining eastwards to India.

Globalisation has been going on for a long time. In the reign of the Emperor Augustus there were already close interconnections across the ocean with Roman Egypt. The profits of this trade funded blossoming civilisations in the subcontinent. Among the knock-on effects were the things we had come to see: sculpture and architecture.

In India it is sometimes hard to tell those two apart. The ‘Five Rathas’, for example, at Mamallapuram — a small town on the coast south of Chennai — look like so many small temples embellished with columns, arcades, internal spaces, statues and elaborate gables. But they are all carved from solid outcrops of rock so, technically at least, could be classified as sculpture.

Of course, the building as sculpture is now a subject of avant-garde artists such as Rachel Whiteread. Her ‘House’, a mould of the interior of a north London terrace dwelling, is slightly reminiscent of the ‘Five Rathas’ — though considerably less decorative. But ‘House’ dates from 1993, approximately 13 centuries later than the ‘Five Rathas’. Those were created in the late 7th century, when, back in England, the Venerable Bede was still young.

This was one of the surprises of the art we saw in India: its age. The 7th and 8th centuries were the heyday of the Pallava dynasty, a ruling house whose main port was at Mamallapuram, although much of the ancient city is now submerged beneath the sea like the medieval port of Dunwich on the Suffolk coast. The Shore Temple, built between 700 and 728, is now sited just above the beach, its stones so eroded by sand and salt winds that they look deliquescent, as if designed by Gaudi. Beyond, ruins of other structures have been discovered beneath the waves. But so much remains that it took us two days to see it all properly.

In a large park right in the centre there is a succession of cave temples quarried into outcrops of rock. Some of these contain relief sculptures that count as masterpieces not just of Indian but of world art. My favourite represents the goddess Durga, mounted on a lion and dressed in a sort of martial bikini, in battle against a buffalo-headed demon armed witha mighty club. When you see it in raked sunlight that slants in through the entrance of the cavern, the effect is astonishingly lively and, as we say in contemporary art, ‘site-specific’.

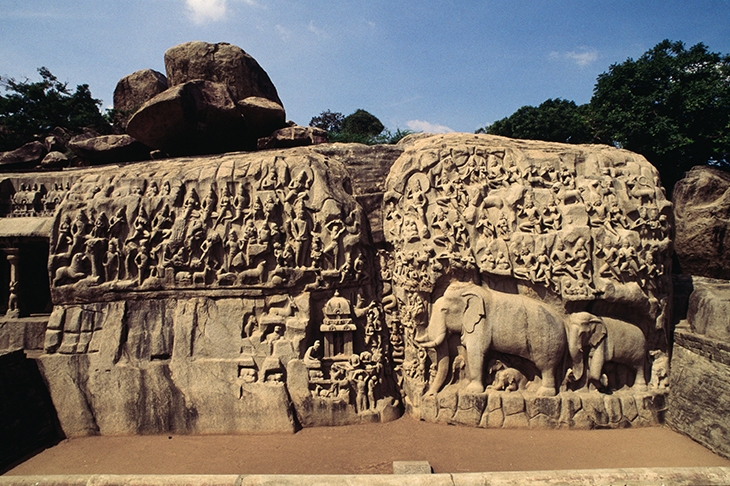

The same is true of the ‘Descent of the Ganges’, the greatest of all the sculptures at Mamallapuram. This is 96 feet across, cut into two huge boulders with a cleft inbetween down which water, representing the sacred river, once flowed. This is an Indian equivalent of the Sistine ceiling: a work into which a whole cosmos is packed. It includes a couple of almost life-sized elephants in high relief, monkeys, the god Shiva, heavenly attendants, men, snake deities known as Nagas, an emaciated ascetic praying anda cat doing the same.

There is a slight dispute as to its precise subject — an alternative title is ‘Arjuna’s Penance’ — but the overall effect is overwhelming. It suggests that the entire animate and inanimate world is teeming with spirits, which seem not so much chiselled from this chunk of stone as released from it.

India itself teems with art. A few hours’ drive from Mamallapuram lie the vast temples of the Chola dynasty. For these places — hugely impressive in themselves — were made the most accomplished bronzes ever cast. The world’s finest collection is housed in a slightly dusty museum in Thanjavur.

A number represent the god Shiva as Nataraja, the dancing lord. Shiva, Hindus believe, both creates and destroys the cosmos in a dance of bliss. It’s an idea — that movement and rhythmic energy are fundamental to the universe — reminiscent of modern physics. The Nataraja also fits the definition of a good sculpture: a thing that can make you feel and think.

Comments