It was vicious. It was frenetic. It was full of rage and class-hatred. It was great

political sport. If you like a serious punch-up, the Commons at mid-day was the place to be. The viewing figures at home were boosted by the many millions of strikers who couldn’t quite make

their local anti-cuts demo and were sitting out the revolution with a nice cup of tea and PMQs on the Parliament channel.

It was vicious. It was frenetic. It was full of rage and class-hatred. It was great

political sport. If you like a serious punch-up, the Commons at mid-day was the place to be. The viewing figures at home were boosted by the many millions of strikers who couldn’t quite make

their local anti-cuts demo and were sitting out the revolution with a nice cup of tea and PMQs on the Parliament channel.

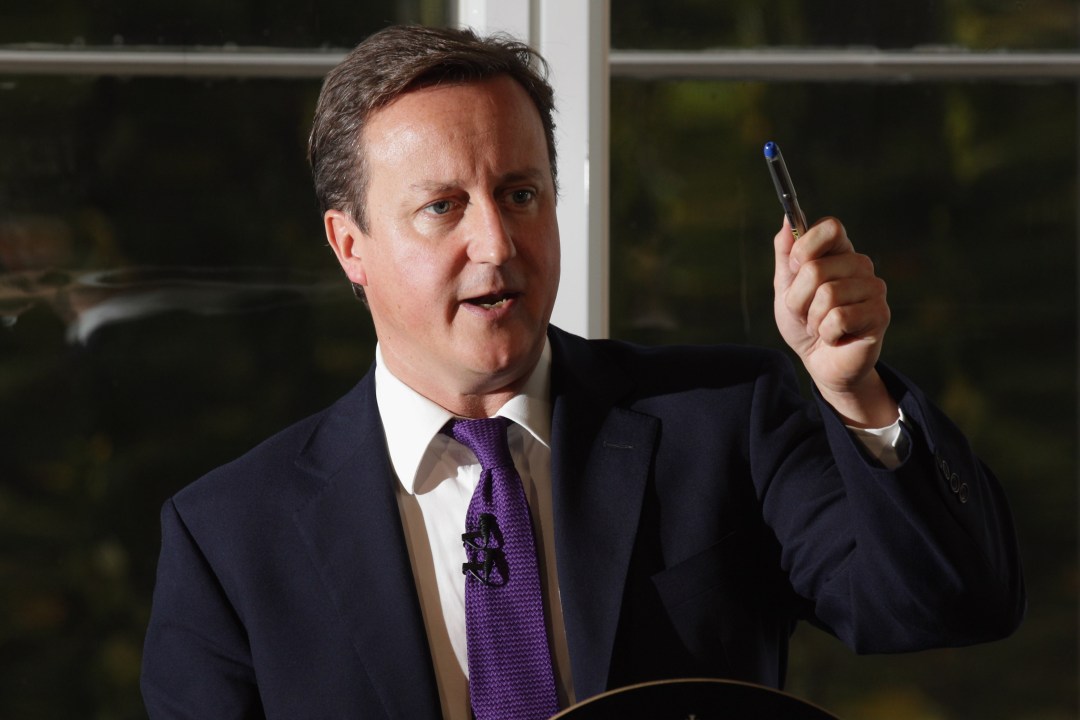

Ed Miliband started by claiming that the PM had been seen in private rubbing his hands, like Moriarty, and boasting that ‘the unions have walked into my trap’. Cameron, although not denying this, slammed the Labour leader for supporting a strike which had been called in the middle of the negotiations. Turning it into a character issue he called Miliband, ‘irresponsible, left-wing and weak.’ He said it twice, in fact, reversing the order the second time, as if searching for its optimum alliterative impact.

Miliband was in ecstasies of class-loathing too. His brows darkened with fury as he accused the PM of demonising underpaid workers and of not understanding the impact of his policies on the poor. At times the Labour leader looked so angry that his face appeared to be ripening before our eyes like a cluster of empurpled grapes.

He moved to detail. Specifically, to the wage freeze. ‘Will he admit that 800,000 people on £15k a year are facing a pay cut?’ Cameron answered a question which was, in one or two respects, similar to this one. ‘Let’s hear some facts about public sector pensions,’ said the prime minister. ‘Anyone earning less than £15k full time will not see any increase in their pension contributions.’

The house was growing so rowdy that the Speaker, Mr Bercow (whose new coat of arms bears the startling prediction that, ‘All Are Equal’), stood up and attempted to apply his new levelling principle to the decibel-count in the chamber. He asked everyone to be equally silent. So everyone was equally noisy. And equally oblivious to Mr Bercow.

When Ed Miliband bellowed out a question about cuts to tax-credits — ‘Families on the minimum wage, taking home £200 a week, will lose a week and a half’s pay!’ — the chamber was so noisy that the prime minister felt free to take a scenic route towards his answer. He blamed Labour for removing the 10p tax rate. Then he praised himself for lifting a million citizens out of tax altogether. And he finished off with ya-boo at Miliband for fiddling the figures while in the Treasury and ‘attacking the working poor.’

As things got rowdier, the issues got cloudier. Julie Hilling (Lab, Bolton), spoke on behalf of ‘Jackie’ a constituent who no longer knew whether she could feed her family. The prime minister told her that Jackie could cheer up because he’d frozen council tax, cut petrol duty, increased child tax-credit and made sure that the UK’s economy was protected from the scourge of soaring interest rates.

Cathy Jamieson (Lab, Co-op Kilmarnock and Loudoun) accused Cameron of freezing working tax-credits and of damning ever more children to child poverty. Cameron replied that he had boosted child tax-credit and added, puzzlingly, that if ‘you increase pensions you see child poverty go up.’ He also claimed that pensions would benefit from ‘a record cash increase next year.’

Something has got out control here. Not the House of Commons but the system of penury-containment. It seems to have proliferated like the Barrier Reef into a thousand categories and sub-sectors. And each group of needy citizens qualifies for a mass of levies and exemptions, of tax-cuts and top-ups, of hand-outs and grab-backs, of allowances and confiscations. It would take a particle physicist to explain it all. The result is that even well-informed observers have no way of knowing whether millions are in mortal peril (the Miliband nightmare) or whether we face an era of tough but manageable hardship, (the Cameron future-fitness programme).

But at least our MPs threw themselves at it full tilt. Many today complained about the cement-mixer levels of shouting and jeering. And the Speaker intervened five times to hush what he called ‘orchestrated heckling.’ He made scant impact. And a good thing too. A debate in Parliament is supposed to be a bloodless duel. If it turns into a bloodless nothing, it loses its soul and its purpose. A House in uproar is a House that cares. Governance shouldn’t be pretty. Rhetorical passion — and the mob-barracking that wants to shout it down — is a mark of vibrancy and integrity in our system.

Lots of democracies around the world present a decorous public face. Most of them are tyrannies.

Comments