Richard Hamilton: Modern Moral Matters

Serpentine Gallery, until 25 April

This year is the 40th anniversary of the Serpentine Gallery, that most welcoming of exhibition venues — the gallery in the park — with its wide views and well-appointed rooms. Expectation rises as the visitor walks through gardens burgeoning with spring, even if it is raining. To start its anniversary year, the Serpentine has mounted an exhibition of Richard Hamilton’s political work entitled (in homage, presumably, to Hogarth) Modern Moral Matters. The show is a real disappointment: the blinds are down to focus the visitor’s attention inward, which might be acceptable if there were riches to be seen. Instead, the galleries are scarcely filled with one of the thinnest exhibitions in a public space I’ve seen for years. I’m staggered that it’s taken three people to curate it.

Don’t get me wrong: I’ve great respect for Richard Hamilton (born 1922), as member of the Independent Group, progenitor of Pop Art and as a painter and printmaker. He’s an artist of considerable probity and international reputation, who has had more retrospective exhibitions than most artists dream of. But his historical status is, to my mind, seriously qualified and even undermined by his lengthy obsession with photography. It is that, rather than his other abiding interest — in making ‘protest’ works, though nothing dates faster than most political art — which accounts for his rather anomalous position today. Norbert Lynton summarised Hamilton’s work as ‘dedicated to exploring style as a symbolic and synthetic language in art and in high-commercial and common advertising, to offering a discourse requiring intelligent attention, and to questioning the traditional distinction between high art and low-brow, popular imagery’. Hamilton’s master is Duchamp, which makes him a kind of adoptive granddaddy for today’s pseudo-conceptual artists, if his abundant learning does not prevent him from recognising their bathetic idiocies. Hence, presumably, his guest appearance at the Serpentine.

I wandered round the exhibition a couple of times in search of work to hold the attention. A whole gallery is devoted to Hamilton’s famous screenprint ‘Swingeing London’ (1968–9): overkill by any but the most adulatory standards. I was curious to see the image traced through its various stages and incarnations (11 versions and variants, including a variety of print media, drawings, collages, even a couple of over-printed images by Hamilton’s confederate Dieter Roth), but the lasting impression was the triumph of idea and technique over absolutely everything else; in the end, over interest.

A press photograph sparked off ‘Swingeing London’, but the appeal of the art Hamilton made from this found image arises from the careful partnership of modern technology with the traditional apparatus of painting, drawing and print-making. For the rest of the exhibits, the more photography dominates them, the less potent they become. Intensity seeps away in the blur of image Hamilton frequently allows. ‘The Citizen’ has a certain punch and ‘The State’ a certain tackiness (presumably deliberate), but the later ‘War Games’, inkjet print on canvas, repels by the crassness of its making. (It’s the dripping blood that really does it.) Is this intended? Does Hamilton so badly want us to turn away in disgust that he is prepared to compromise the aesthetic content of his work?

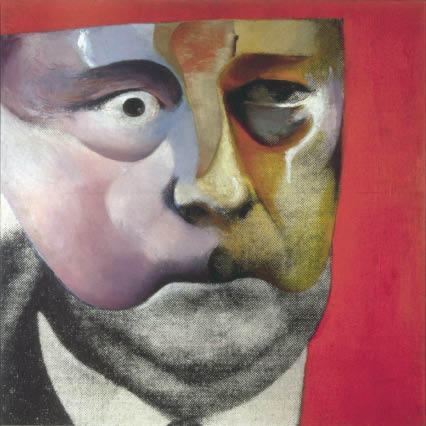

Perhaps. Such an anti-art stand would be worthy of Duchamp’s torch-bearer. Again and again going round this show, I felt that Hamilton had sacrificed his art for ideas that would not live on, out of their period or out of context. His unsatisfactory later images — neither painting nor photography — made me long for his early work, so formally brilliant, incisive and witty. There isn’t even enough material here properly to fill the Serpentine’s galleries. But at least there’s something good to look at on the way out (and I don’t mean the tiresome video installation of Mrs Thatcher in the treatment room, which looks even slighter today than it did in the 1980s). One of Hamilton’s most enduring images is ‘Portrait of Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland’ (1964). Here it is, with two related works.

The collage is centrally placed, with a drawing for it in crayon and gouache on the left, and a copper on aluminium relief on the right. The drawing is the most interesting piece, sensitive and suggestive. The relief has a motorised disc behind it which changes the monster’s eyes. (Rather too quickly, I thought, but attracting considerable passing interest nonetheless.) The collage is a powerful statement, combining paint with photography in an original and provocative way. I doubt whether many of the young people who paused briefly to look at these three works had a clue who Hugh Gaitskell was, but such is the power of the art that this does not matter. As for the rest of the exhibition — sadly, not swingeing enough.

The Serpentine has such a rich exhibiting history that you’d have thought it might be the subject for celebration in this anniversary year. Not if you consult the programme of forthcoming shows, though intriguingly the autumn exhibition has yet to be announced and might still be a tribute to past achievements to remind people that it hasn’t always shown the narrow conceptual taste of today’s programmers. Why must art be so fashion-conscious and ghettoised? The Serpentine should be showing John Hoyland or that modern American master shamefully neglected in this country, Wayne Thiebaud (born 1920). But both are real painters, and real painting is out of fashion among the thin-blooded curators who dominate the English art world today.

By way of contrast, I’d like to mention a couple of shows of painters whose work deserves more attention. In Bath, at The Chapel Row Gallery (until 4 May), are drawings and paintings by Mike Harvey (born 1946). Harvey is a figurative painter in the Kitaj mould who makes his living as a builder. He has a keen eye for the foibles of society and a satirical edge to his narratives. He is a powerful draughtsman and designs his paintings better than most, while his colour sense is individual and risky. His paintings are beginning to attract a wider public, as people respond to their wit and originality. A late developer, but a talent to watch.

Hsiao-Mei Lin (born 1971) is a very different kind of artist, a painter of reverie and dream, who celebrates the natural world through images of cosmic flux. She is a passionate scuba diver, and her experiences underwater have clearly fed into her imagery. Her paintings may superficially appear to be abstract, but in fact bear reference to all sorts of natural phenomena, from Arctic landscape to ocean depths to the firmament above. And over all hovers the artist’s inquiring spirit in tandem with her firm religious belief. I particularly like her small square oil-on-gesso panels, in which landscape is as playful and full of possibilities as on the fifth day of Creation. Her new work is at Adam Gallery, 24 Cork Street, W1, until 17 April. Recommended.

Comments