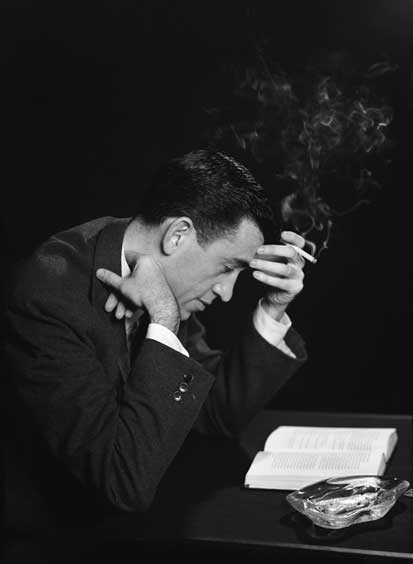

This biography has somewhat more news value than most literary biographies. Its subject worked hard to ensure that. After 1965, J.D. Salinger, having published one novel, a volume of short stories and two pairs of novellas, withdrew permanently from public life. His last publication, a long story entitled ‘Hapworth 16, 1924’, was never printed in hard covers.

Subsequently, he went to some effort to control what was known, and could be written, about him. He retired to Cornish, New Hampshire, living comfortably on the immense, ongoing sales of his single novel, The Catcher in the Rye. From there, information occasionally leaked out. A fan might extract a couple of rebarbative sentences from his idol. A mistress wrote her memoirs, years after her relationship with Salinger, and his daughter a volume designed to serve her own ends in therapy. A number of witnesses suggested that he had gone on writing until his death in 2010, storing the finished books in a safe.

This biography appears to contain something more than idle speculation. Its revelations about Salinger’s life are mixed in nature, and include some genuinely intrusive discoveries. The first is that Salinger had only one testicle, out of which David Shields and Shane Salerno conjure rich speculation about shame and emotional difficulties. They have also discovered Jean Miller — the girl Salinger started wooing when she was 14, finally seduced and then immediately abandoned — and persuaded her to talk. We are told in detail about Salinger’s horrific war experiences: he was one of the first American soldiers to enter Dachau. The authors have also tried to unearth the truth about a mysterious first marriage to a German woman at the end of the war, which lasted barely a year, and suggest that it may have foundered because she was discovered to be a Gestapo informant. In the absence of any corroboration in the German archives, we have to regard this one as bold.

Bold, too, is their final claim. They not only affirm that those unpublished manuscripts exist; they describe their nature and assure us that they are to be published between 2015 and 2020. It is not clear that this information comes from the Salinger estate, but it is certainly very detailed.

The major addition is a novel, based on Salinger’s first marriage, in the setting of the war; and there is a novella in the form of a counter-intelligence agent’s diary, set in the last days of the war. Did Salinger take decades to assimilate his wartime experiences and address them directly? There are also five previously unpublished stories about the Glass family, and several about Holden Caulfield and his family.

In addition, there is a ‘manual of Vedanta’, the Indian philosophy deriving from the Upanishads, that Salinger devoted much of his life practising, including some fables. Whether there is anything more than this — and how accurate this account really is — will be discovered in a couple of years’ time. If this is all, the work rate might well be consistent with the Salinger who, even in his fecund youth, took 20 years to publish one short novel and 14 pieces of short fiction.

And will it add up to much anyway? Though the two wartime pieces sound intriguing, I doubt whether any of this will really be worth reading. There was an interesting case, four years ago, when the Nabokov estate finally published the unfinished The Original of Laura. After years of tantalised speculation, it was discovered to be awful rubbish. Admirers who had been hoping for a gem along the lines of Lolita and Pale Fire had forgotten that when Nabokov started work on Laura he had just published the dire Look at the Harlequins! His best work was decades in the past.

Similarly, anyone hoping for top-rate Salinger in the unpublished work must come to terms with the fact that it was written on a trajectory just preceded by Seymour: An Introduction and ‘Hapworth 16, 1924’. Those two last stories are nightmarishly voluble, unspecific, in love with their own noise and verging on gibberish. They show all the signs of a writer refusing to be edited and withdrawing from any engagement with the reader. Writers cannot be entirely divorced from their readers, and Salinger’s long, solipsistic retirement would not be likely to produce good results. He always tended to love his characters — or want to be thought to love his characters — more than life itself. After 1955, his work became what Lord Chesterfield thought of the novel: ‘absurd romances … where characters that never existed are insipidly displayed, and sentiments that were never felt pompously described’. He lacked, in his work, the splinter of ice in the heart — saving that, if this biography is to be believed, for his personal relations.

The same solipsism is apparent even in the earlier published work. Though the voice is one of the main charms of The Catcher in the Rye, Salinger has quite a narrow range of social types at his disposal. In For Esmé— with Love and Squalor he attempts an upper-class English schoolgirl, and the result is hopeless: ‘Usually, I’m not terribly gregarious… I purely came over because I thought you looked extremely lonely. You have an extremely sensitive face.’ Salinger will probably always be remembered as the author of just one classic novel.

This biography is curiously written and needs to be read with a sceptical eye. Instead of a narrative, it is constructed out of single-voice paragraphs, each assigned to a source. The effect is to imitate talking-heads television documentaries. The authors themselves are permitted to speak individual paragraphs, too, as if they were witnesses and not mere compilers.

They have found some interesting sources — including Jean Miller — but many are not quite what they seem. The wartime sections, in particular, are taken from more general accounts, whose authors may never even have heard of Salinger. Some apparently authoritative statements are just footling speculation by literary critics from Canadian academic journals. One intrusive fan reports Salinger telling him: ‘Well, I understand, but I’m becoming embittered … Nothing one man can say can help another. Each must make his own way’, and on, in a long speech. The reader is sceptical: but that scepticism should have been exercised in the first place by the authors.

This is a biography that inevitably tries to conceal a paucity of evidence; there is not even an index, and the footnotes are maddeningly incomplete. Whether it was worth writing at all will depend on the quality of what is published between 2015 and 2020.

Comments