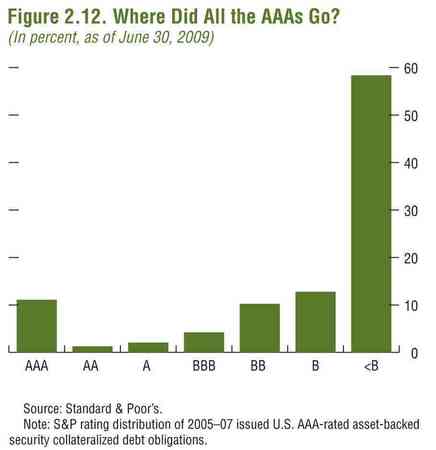

The further revelations about the astonishing costs of the bank bailouts so far indicate just how much taxpayers’ money is now being used to plug the holes in the banking system. A key cause of the bank crisis is explained by the above IMF graph, charting the decline of some of the trillions of AAA structured credit assets created during the boom. AAA means “extremely strong capacity to meet financial commitments”, but now over 80% of the US AAA Collateralised Debt Obligations (CDOs) created between 2005 and 2007 are rated BB or lower, somewhere between junk bonds and default (and in some cases almost entirely worthless).

In terms of getting things totally wrong this is hard to beat. The belief in the end of boom and bust was shared as readily by the large investment banks and credit ratings agencies as it was by Gordon Brown, creating near endless amounts of “risk free” debt providing rocket fuel for property lending, private equity deals, and naturally, bonus pools. Chopping debt into lots of little pieces and putting it back together again offered a fat fee at ever turn.

For debt that was meant to be of such high quality, banks were exempted from holding capital in reserve against the prospect of any future losses. As Vince Cable brought to light earlier this year, these were such good bets that British banks and building societies hoovered them up – the extra yield for seemingly no risk proving an irresistible lure. Purchase of these kind of assets was one of the key mechanisms by which UK banks became so exposed to asset price bubbles and losses around the world. It was concern about the true nature of these assets – brought about by the collapse of IKB in Germany in July 2007 – which triggered the credit crunch, and the stories which started appearing on front pages in the summer of 2007 about banks being too scared to lend to each other. However revolutionary investment bankers thought they were, the basic fact of banking – that you need to lend to people who can and will repay you – had not changed.

Disaster ensued. From early August 2007 the banking system was increasingly reliant on massive injections of central bank liquidity as the interbank lending market collapsed. Despite the run on Northern Rock, Labour sailed on oblivious to the scale of the fermenting problem. No doubt assured about the good health of all these assets by the usual investment bank suspects, it seemed much preferable to blame evil short sellers and rumour mongerers for issues in the banking system than ask questions. Despite a further serious bank collapse with Bradford and Bingley and issues at various building societies, the penny still did not drop. A telling contrast is provided by the manner in which the Swiss dealt with problems with AAA assets at UBS through 2007 and early 2008, greatly mitigating the end costs and risks to taxpayers – the report into losses their MP’s demanded still providing one of the best windows into how this disaster happened.

It was only when faced with global meltdown in early October 2008 that the penny finally dropped. The run on Northern Rock demonstrated that when depositors start fleeing with their money, government’s options are not great: either guarantee the bank or let it fail. A solvent government can always stop a bank run in it’s tracks by picking up the costs. The 15 months of delay and denial since the start of the crisis simply left few options but to push the losses of the banks onto the taxpayer. We are now starting to find out the true costs of this: £130bn of direct injections and hundred of billions of pounds more potentially at risk.

Bank of England statistics detailing lending to non-financial companies shows that the flow of credit to British business has collapsed this year. In paying 10s of millions of pounds for “advice” to the very same investment banks responsible for the AAA asset fiasco, it looks like this naive and inexperienced government has simply let investment bankers run rings around them. Rather than save the world, Gordon Brown simply saved the bonus pool.

Comments