Knowledge can be successfully transmitted and received only by those who recognise its value. If our governments have regarded education as valuable, however, it is usually as a means to some political goal unconnected with knowledge. As a result, our school system, once the best in the world, is now no better than the average developed country for numeracy and literacy.

Many on the left see schooling as a form of social engineering, the purpose of which is to produce a classless society. Equality is the real value, and when knowledge gets in the way (as it often does) it must be downgraded or set aside. Many on the right look to education for the skills that the country needs in order to maintain our economic position in a competitive world. On this view, those children who show no aptitude in hard subjects, or who take up too much classroom time to achieve too little, should not be allowed to hold back the ones whose skills and energies we all supposedly depend upon.

Those two visions have fought each other in the world of politics, and descended from there into the classroom. Teachers meanwhile have been forced to take a back seat, spectators of a quarrel that can only damage the thing that is most important to them, which is the future of the children in their care.

The abolition of the 11-plus examination and the destruction of state grammar schools, the amalgamation of the CSE and O-level examinations, the flight from hard subjects at both GCSE and A-level, and the expansion of the curriculum into areas where opinion rather than knowledge sets the standard: all those changes were motivated by the commitment to equality. Until recently very few reforms stemmed from the desire to support the high-fliers, or to improve the country’s standing in the hard sciences. And right-wingers will say that our standards have declined because the left has triumphed. In Kingsley Amis’s words, more means worse.

But one thought should now be obvious, which is that ideological conflicts have undermined the real motive on which education depends. This has nothing to do with social engineering, of the leftist or the rightist kind. Education depends on the love of knowledge and the desire to impart it. The ones who suffer most from the refusal to recognise that simple truth are the children. Our country is full of people who know things, and children who want to learn things. A successful education system brings the two together, so that knowledge can pass between them. That is how the system grew during the 18th and 19th centuries, and why it was, until the politicians got wind of it, one of our national treasures.

The conclusion to draw is that schools should be liberated from the politicians and given back to the people. The school is a paradigm of the ‘little platoon’ extolled by Edmund Burke. It ought to be a place of free co-operation, in which each member has a shared commitment to the collective purpose. It should be a place of teams and clubs and experiments, of choirs and bands and play-acting, of exploration, debate and inquiry. All those things occur naturally when adults with knowledge come into proximity with children eager for a share of it. It is in the classroom that the relation of trust between teacher and pupil is established, and it is when the school can set its timetable, its budget and its educational goals that an ethos of commitment will emerge.

Of course, it has been acknowledged for two centuries that schools must account for their results to the state — which is the highest legal authority. But accountability to the state does not mean control by the state. Schools thrive in the way that other enterprises thrive, by assuming responsibility for their activities and planting in their members the seeds of a shared commitment.

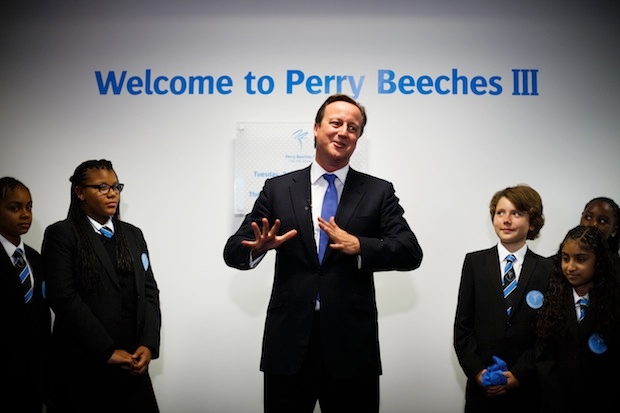

For this reason we should surely welcome the present government’s policy of creating schools outside the control of local authorities. A free school can settle its own curriculum and contracts of employment. It can open the way for those with unused knowledge to impart it in the classroom, and for volunteers to help with extra-curricular activity. Anyone can apply to set up such a school, provided they have sufficient educational and financial expertise in their team, and the willingness to make a substantial time commitment. Parents, local businesses and volunteers can all join in the enterprise, whose goal is to rescue children from disadvantage and once again to open the channels through which the social and intellectual capital of one generation can flow into the brains and bodies of the next.

The educationists complain that these free schools provide a free education to the middle classes, and that they do so by withdrawing the more able children from the state schools on which the poorer social strata depend. You still hear this kind of complaint from the Labour front benches, including from the mouth of education spokesman Tristram Hunt who, as the Oxford-educated son of a lord, can just about maintain the fiction that he is not middle class. But it has no relation to the realities.

Free schools take in children of all abilities and backgrounds. I have visited Greenwich Free School, which is in a deprived area, with 30 per cent of pupils on free school meals and the characteristic ethnic mix of an inner London borough. I encountered the same atmosphere of co-operation between pupils and teachers. To set up a free school in such an area, with the goal of taking children of all abilities, is to take an undeniable risk, and it is too early to say whether the risk has paid off. Nevertheless, the venture has the support of parents in the neighbourhood, with seven applicants for every place. And touring the school with two little girls who wanted me to see into every classroom, I felt the vibrations of their manifest joy that this place with real lessons, real teachers and real after-school activities had come to rescue them. And let’s be clear: in our inner cities, rescue is what education means.

My guides bombarded me with questions about my own career. The ability to present oneself freely and engagingly to a person with useful information is part of what these two children had learned. They had absorbed from their school its fundamental meaning, which is that we live and prosper by taking responsibility for our lives. For too long our education system has been opposed to that fundamental principle, regimenting the classroom, the curriculum and the ethos of our schools according to a frankly antiquated idea of social progress. When schools have become locked into goals that are both futile and unachievable, it is surely time to liberate them, to give them back to the parents, teachers and children whose property they are.

Comments