At one of Lord Ashcroft’s focus groups recently, participants were asked what jobs they thought might suit politicians if they were not, well, politicians. In Edinburgh, one respondent unkindly suggested Nicola Sturgeon would make an excellent traffic warden. For her part poor Kezia Dugdale – I’m afraid ‘Poor Kezia Dugdale’ has become the accepted form of labelling the Scottish Labour leader – was reckoned to be just the sort of person who would thrive working in a pet rescue centre.

There are many times that must seem preferable to leading the Labour party in Scotland. For the whole of this campaign Ms Dugdale has suggested that the very last thing Scotland, and indeed the United Kingdom, needs is a second referendum on independence. No, no, no, she says. It is time to focus on other matters, putting the divisions of the past behind us.

This recognises that the Labour party of 2017 is not the Labour party that existed in 2014. It is, in the first instance, very much smaller. But also very much more Unionist, no matter how stridently Labour politicians shy away from accepting that label. Fully a third of Labour’s habitual voters voted Yes in 2014 and the vast majority of them then left the erstwhile people’s party and gave their votes to the SNP. Labour became a Unionist party by accident and by default.

This left it in a terrible position. It cannot win again in Scotland until it regains those lost Yes voters but it cannot regain those lost Yes voters without risking the loss of the No voters it has retained and who now constitute the overwhelming majority of Labour supporters.

Poor Kezia Dugdale, then, is trapped. Damned if she goes in one direction; just as damned if she goes in another. You begin to understand why Labour would rather not talk about the constitution.

Still, in recent months her language has hardened. She made her choice and it was to stick with the voters she still has. Only Labour can stand up to the Tories and the SNP alike; only Labour will put social justice first. Only Labour can move us on from a paralysing constitutional debate that is, in any case, increasingly subject to the law of diminishing returns. That means no second referendum any time soon. Not least because Labour is a party that believes in fairness and there’s nothing fair about a referendum every five years until such point as you finally achieve the result you were wanting all along.

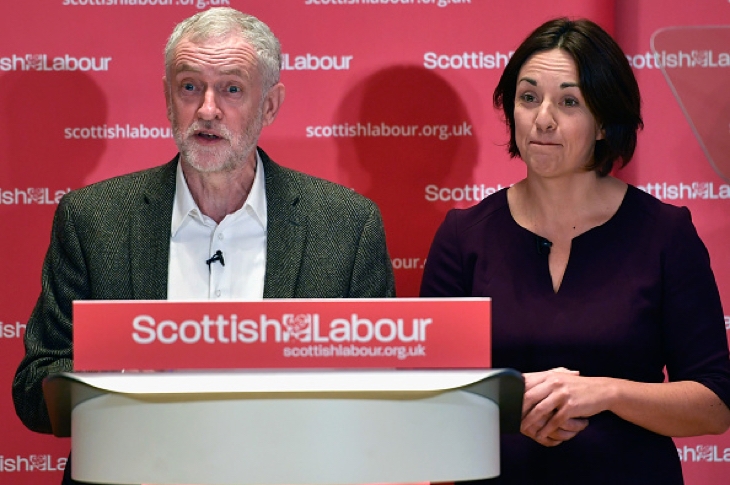

The problem is that Jeremy Corbyn cannot see a line without unholding it. Yesterday he came to Glasgow – safely away from Scottish Labour’s two target seats in Edinburgh South and East Lothian – where he addressed a fervent crown of left-wing true believers. For a while, he managed to stick to the script – a script that had been ‘run past’ the Scottish leadership – saying that another independence referendum was ‘unwanted and unnecessary’.

Then it all began to go wrong. First, he departed from that prepared script. Corbyn was supposed to say Labour’s vision ‘rejects Scottish independence’ but he changed that to Labour ‘challenges the notion of Scottish independence’.

Worse – at least for poor Kezia Dugdale – was to come. Asked by Bauer and Global radio what he would do if he were Prime Minister and Nicola Sturgeon demanded a second referendum, Corbyn said he was open to the idea:

‘I’ll obviously open discussions with the government in Scotland and listen very carefully to what the Scottish parliament says. I would ask them to think very carefully about it and suggest it would be better to have this question dealt with at the conclusion of what are very serious and important Brexit negotiations.’

In other words, yes, there could be a referendum sometime soon. How this can be squared with his claim that ‘There will be no deals’ with the SNP must, I am afraid, remain a mystery. He only had to hold the line for two minutes and he could not do it. The questionable or problematic policies he espouses are one thing; the political ineptitude is quite another.

And yet, despite undermining the party’s Scottish leader, you can find some reason for Corbyn’s approach. In the first place, it is reasonable to infer that he is temperamentally sympathetic to Scottish independence. After all, those Scots who agree with Corbyn on most things largely voted for independence in 2014.

Secondly, he cares little about actually winning seats in Scotland. He is more interested in cementing the Corbynite revolution. If he can bring some left-wing Yessers back into the fold then that’s worth the loss of Labour Unionists who were, in any case, never part of Project Corbyn in the first place. It won’t win seats, but that’s not the goal.

But it is a gift to Ruth Davidson and her Conservatives who have, much to poor Kezia Dugdale’s irritation, been arguing for months that only the Tories can be properly trusted to stand up to the SNP. And since the non-SNP half of Scotland desperately wants someone to stand up to the SNP this is a message that, as they say, has cut-through with a decent segment of the population. You don’t need to be a Conservative to vote for a Tory candidate.

Moreover, senior figures within Labour and the Lib Dems agree with Davidson that independence is the only issue that really matters, the only subject that really engages voters on the fabled doorsteps of Scotland. Health and education and Brexit and the economy have their place but independence is mentioned more often than the rest of those concerns combined. You might not wish it to be like this but this is the way it is. (This is why, at least thus far, Theresa May’s dismal, shambolic, entertainingly useless, campaign has had little impact one way or the other in Scotland.)

Now you may object that Corbyn’s line is not all that different from May’s suggestion that ‘now is not the time’ for a second referendum. You might further suggest that any UK government is going to have to talk to any Scottish government about the constitution at some point. And you would, of course, have a point.

But there are times when such points can be made and there are ways in which those points can be made too that do not undermine what is, notionally at least, your own party’s notional position. Corbyn, as always, doesn’t care about that. Until now the prospect of a second referendum before 2020 had been fading surprisingly quickly. Corbyn, if he were elected, would make one by the end of 2019 vastly more likely.

And while, hitherto, the Tory party has not been able to put Corbyn in Nicola Sturgeon’s handbag and make that seem a credible, plausible, mind-concentrating position, it may now see an opportunity to do so.

Comments