In his new book Classified: Secrecy and The State In Modern Britain, Dr Christopher Moran gives an account of the British state’s long obsession with secrecy, and the various methods it used to prevent information leaking into the public domain.

Using a number of hitherto declassified documents, unpublished letters, as well as various interviews with key officials and journalists, Moran’s book explores the subtle approach used by the British government in their attempt to silence members of the civil service, and journalists, from speaking out about information that was deemed classified.

Moran points out the inherent hypocrisy at work, when leading political figures of the 20th century, such as Lloyd George and Winston Churchill, recognized no law regarding secrecy, when it came to writing their own memoirs.

The book analyses key events in British post-war history, including: the Suez crisis, the D-Notice Affair and the treachery of the Cambridge spies.

Moran also questions the new era of offensive information management, and asks if this so called transparency is simply another method of maintaining further secrets within the British state.

Christopher Moran is currently an Assistant Professor in the US National Security British Academy and a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of Politics and International Studies (PAIS) at Warwick University.

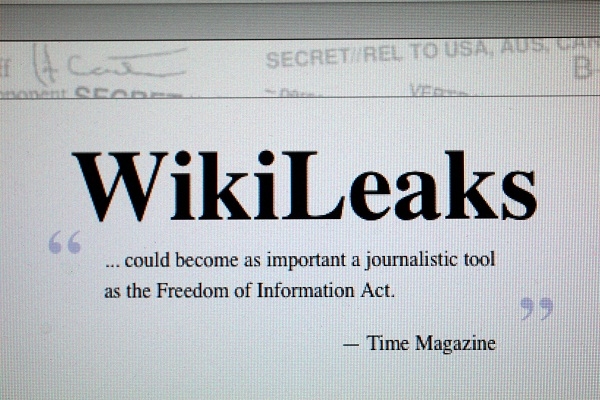

He spoke to the Spectator about how the D-Notice Affair was a watershed in British journalism, why Wikileaks could mean less transparency from government, and why the Freedom of Information Act has resulted in a false sense of transparency.

How much of a threat was former Prime Minister, Lloyd George, to state secrecy, before the Second World War?

Civil servants didn’t believe that they had a right to censor Lloyd George for what he wanted to say in his memoirs. I found one document within the archives where King George V said to one of Lloyd George’s aids, that he greatly disapproved of some of the material that Lloyd George was putting into his book: particularly content used to attack certain personalities from the Great War period. Then Lloyd George snaps and says: ‘why doesn’t The King like my book? He can go to hell, I owe him nothing, he owes his throne to me.’

It’s perhaps the most damming review of a sitting monarch in recent British history.

Winston Churchill also seemed to think he was above the state’s secrecy laws, but was he more of a shrewd operator than Lloyd George?

Churchill did play fast and loose with the rules of official secrecy, but yes, he was also a very clever operator. He had the sense not to impose constraining precedents whilst he was in office. So he never brought in any new legislation that would limit him when he was retired, or when he was writing. When he was in government he cut several deals with the cabinet secretary to ensure that every piece of documentation would be available to him when it came to writing his Second World War histories.

Was the D-Notice Affair a watershed in British journalism, in terms of the relationship between journalists and the state?

I think it was. A lot of journalists — in light of Harold Wilson’s heavy-handed approach to The Daily Express in 1967 — just walked away from the D-Notice Committee: which was a very valuable mechanism that the government had to moderate the content in newspapers.

Many journalists afterwards refused to abide by this voluntary contact. For the Secret State, this became very worrying, because you had journalists becoming very good at finding information, but now they were operating of their own will, and not willing to tell governments what they found. You also had a sort of cult of investigative journalism emerging after the D-Notice Affair.

How important was Harold Wilson’s decision to amend the Public Records Act in 1967 — changing the 50-year rule for declassification of most official records, to a 30-year rule?

There are certain indications within the records that there might have been an alternative political motive for Wilson to do this. By reducing the 50-year rule to a 30-year rule, he knew that researchers would start reading Conservative government records pertaining to the appeasement era of 1938. Politically, this was a good thing for Wilson, because people were starting to read some of the errors that Neville Chamberlain and the Conservative government had made in the run up to the Second World War.

How significant was the intelligence gathered at Bletchley Park during the Second World War to secure an Allied victory?

When it was revealed in 1974 — with the release of Captain Winterbotham’s book, The Ultra Secret, which was sanctioned by government, that a secret operation was ongoing during the Second World War at Bletchley Park, codenamed Ultra — the immediate response was that Ultra was an absolute war winner. There was much exaggeration that Ultra on its own had won the Second World War. Over time, military historians have reassessed that orthodoxy. They now argue that while Ultra did shorten the war, it didn’t guarantee victory, because ultimately soldiers still had to clash on the battlefield. The argument historians now hold is that Ultra shortened the war by a period of two to four years. That is not to diminish what went on at Bletchley Park either. Clearly what happened there saved over a million Allied lives.

One of the central arguments in your book is that when defensive strategies of information management fail, the secret state goes on the offensive releasing information?

Well one of the lessons the secret state learned throughout the 20th century was that it’s almost impossible to maintain absolute secrecy for a number of reasons. Firstly, journalists had become more skilled and daring, and secondly, memoir writers were operating by a law unto themselves. By the late 1950s, and certainly by the late 1990s, and 2000s, senior officials within government are saying: not only is this impractical, it’s not even productive, because we are not getting our message across.

In this context, they then think: if you can’t beat them, join them. So in order to get their message into the public domain, they start to publish official histories. You then get this shift from this offensive approach, to information management: where the secret state is willing to offer information into the public domain.

You say that Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s oversaw a legendary period of Whitehall secrecy. Was this her personal belief, rather than the culture within the Conservative Party at the time?

I think Thatcher herself would be proud to admit that when it came to the work of the intelligence services, she wanted them to operate in secret. She had no time for journalists like Chapman Pincher, writing articles on MI5 or MI6. Thatcher was the last breed of Crown Servants who really believed that you could return to that age of absolute secrecy that existed in the 1920s.

Then in the New Labour years, Tony Blair took quite the opposite approach…

What you had during the Blair years was this politicization of classified material. It was used for political ends and put into the public domain. Blair happily put intelligence into his various reports running up to the Iraq War in 2003.

Would it be correct in saying that state secrecy in Britain today is still prominent, but that we are fed the illusion of transparency through the public relations machine?

That is the big question: to what extent are the initiatives we have seen in the last twenty years emblematic of a unilateral reduction of secrecy? Or are they just PR exercises? There is no doubt that government has opened up, though – particularly when you see spy chiefs talking in the public domain, or declassified documents coming into the National Archives at Kew. This would not have happened at the height of the Cold War. Ostensibly, Britain has become a more open country; but I would consider researchers, and the public at large, as the reason behind that. We shouldn’t simply accept that the society or intelligence is more open. There has to be a rationale behind this.

You’ve also come to the conclusion that Wikileaks could mean less openness from state in the long term?

Although Wikileaks was initially thought to be this glorious moment in freedom of information, there is a potential negative effect from it. As these candid discussions happen constantly on the internet, we could see an increase in the sofa-style-government that we saw in the Tony Blair days: with just one minister, and maybe two advisors, sitting in a room committing nothing to paper.

For a historian this is obviously problematic?

Absolutely. We rely heavily on the 30-year rule: where the state declassifies documents within thirty years. Fast forward another 30 years, and you have a potentially worrying scenario, where we find that the archives are empty.

Did the Freedom of Information Act implemented in 2005, again, create a false sense of transparency?

Many senior civil servants I have spoken to in Whitehall have suggested that that when the act came into force in January 2005, they became nervous about what they would put down on paper.

What has been your own experience of gleaning information since the act was implemented?

I would say my personal experience of requesting information has a success rate of 50/50. The only way to be successful with the Freedom of Information Act is to be very specific with your request. The problem is that unless someone from within Whitehall, or the national archives has told you a certain document exists: it’s very difficult to get information out of the system. To use the Freedom of Information Act and get proper results, you still have to rely on good contacts, and informants to let you know what is being held in the vaults.

Comments