Western Sicily has been a crucible of aspiration and grandeur: the human condition at its most exalted: unsurpassable art and architecture. It started in the Greek era. Sicilian agriculture produced abundance. Trade with north Africa turned Demeter’s bounty into gold. With this wealth, Greek colonists built the temple cities of Selinunte and Agrigento, plus other glories such as the temple at Segesta. The modern traveller, seeing only harmony, might assume that the ancient inhabitants must have been uniquely blessed. In earlier generations, the best preserved temple in Agrigento was known as the Temple of Concord.

This was an error. That was not its name and there never was much concord. Empedocles of Agrigento claimed that mankind was governed by the twin forces of love and strife. In Sicily, strife was usually in the ascendant. Wealth aroused envy, and almost constant warfare. The island was also a crucible of cruelty. The terrible fate of the Athenian captives after the failed expedition — one of the most moving passages in Thucydides — was played out in the east. But western Sicily witnessed equally bloody events, lacking only a chronicler. In the sixth century bc, in an attempt to placate the then tyrant, Phalaris, an Agrigento blacksmith, built a hollow bull large enough to contain a man. Put it on a fire, and the chosen sufferer would roar like a bull as he roasted to death. This availed the blacksmith naught. He was one of the first victims of his infernal machine. In Sicily, as in less favoured regions, human life could often be a cry of pain. The temples should not only be seen as a joyous expression of architectural genius. They were built in a vain attempt to placate the gods.

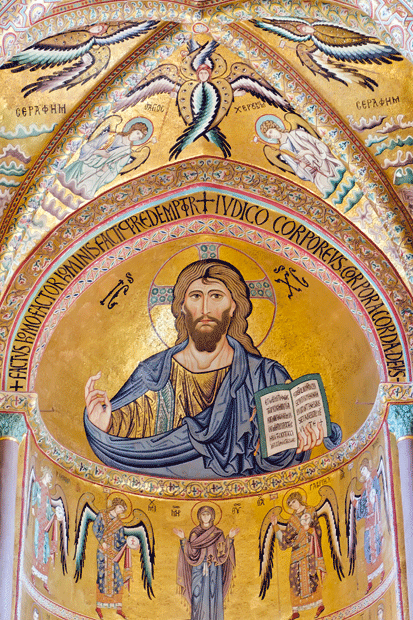

Fifteen hundred years later, there was a similar occurrence. King Roger II was caught in a storm. He vowed that if he survived, he would built a church on the nearest headland, or cefalù, the Greek word. He lived, and kept his vow. The result is one of the glorious achievements of a great era. A couple of hundred years earlier, the king’s ancestors were Norse brigands who had fought their way from Scandinavia to Normandy by fire and slaughter. But in 1061, Roger’s father, Roger I, conquered Sicily and began an artistic efflorescence. Even Gibbon is almost rendered uncritical: ‘The establishment of the Kingdoms of the Normans in Naples and Sicily is an event most romantic in its origin.’ The Norman rulers were warriors and poets, diplomats and artists. They summoned the finest talents in Europe to their courts, and usually practised religious toleration, employing Jewish counsellors and Arab craftsmen. Their descendant Frederick II of Hohenstaufen, stupor mundi, carried on the great tradition, which then expired. But the superb buildings and frescoes still leave one stupefied with delight.

I had the good fortune to see them on a tour organised by Charles Fitzroy of Fine Art Travel. Charles and his wife Diana take an immense amount of trouble. You do not just visit well-known sites, but palazzi which are normally closed. However well-travelled you may be, Charles guarantees his own stupor mundi.

Comments