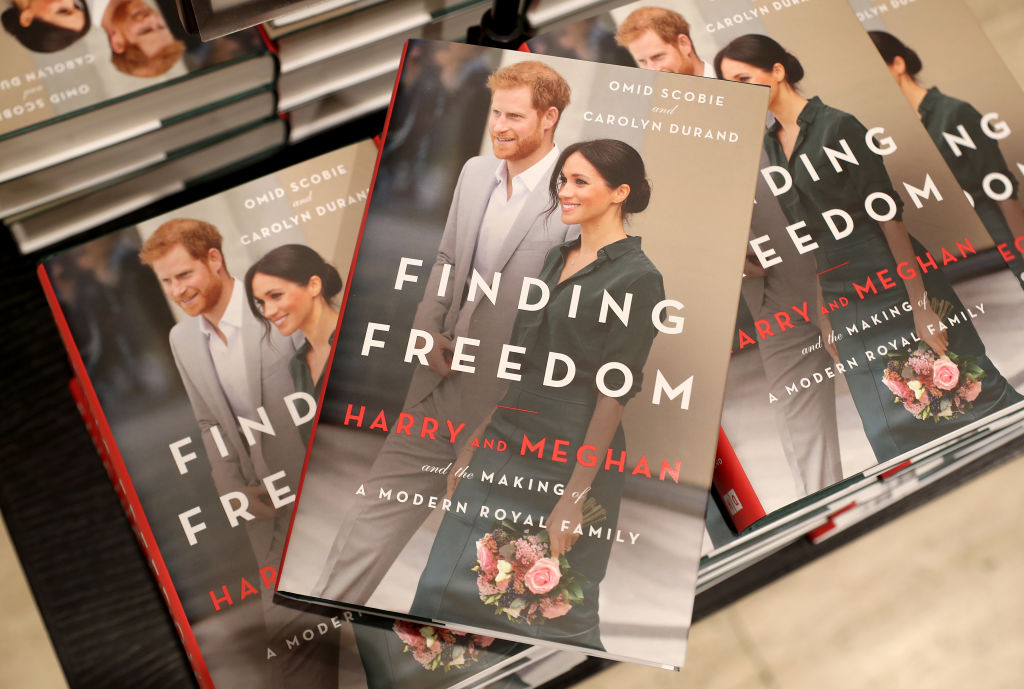

Last year, the apparently definitive biography of Harry and Meghan, Finding Freedom by Omid Scobie and Carolyn Durand, was published, and immediately became a bestseller, despite Harry and Meghan only having reached the tender ages of 36 and 39.

It seemed inevitable that as soon as the biography had hit the shelves, it would be superseded by events. Sure enough, in the light of the Oprah interview, Scobie and Durand have updated the book for its paperback publication. A news report suggested that extra chapters will cover ‘their interview with Oprah Winfrey, allegations against Meghan over the bullying of royal staff, which she denies, and Prince Philip’s death.’ The implication is that, even if readers already bought the hardback edition last year, there will be yet more revelatory and explosive facts detailed within the additional chapters, as the story continues to develop.

And herein lies the problem with writing biographies about living subjects. Scobie and Durand are trying to chart an ever-changing series of events, much like newspaper columnists. The challenges of constructing a definitive book about subjects who might well do or say something far more newsworthy immediately after publication – as in the case of Finding Freedom – mean that one is either dragged into endless rewrites and new editions as further material comes to light, or alternatively the book would become obsolete almost immediately.

Biographers should think carefully before attempting to cover living subjects

Journalism is able to adapt to this ever-changing influx of new information, especially given the rise of the online form over two decades. It is easy to correct an inaccurate story, or update it as new information comes to light. But a biography is, by its very nature, a fixed entity. On the one hand, publishers thrive on the scope for new editions. If the subject is as lucrative as Harry and Meghan, a throng of new versions may seem to make financial sense. But they also risk creating buyer fatigue – no matter how scandalous the revelations, every new edition depletes the worth of the original book.

A biography should surely look at a life in the round; it should be an examination of a subject’s entire career and work. It is extremely difficult to write about constantly changing events with any degree of authority. Had someone attempted to write a biography of Prince Harry when he was aged 32, they would have come to a series of different conclusions about his life than Scobie and Durand did. And it seems inevitable that a biographer who wrote about the Duke of Sussex at 52 would find him almost another subject by then, too.

Having written works of historical biographies about long-dead poets and royalty, the conundrum of taking on a living subject is not one I’m willing to tackle. Authorised accounts of a life are often bland, especially if the subject has copy approval, and unauthorised accounts run the risk, at best, of falling back on well-worn sources and second-hand existing material, and, at worst, of opening their creators up to a libel suit from an aggrieved subject.

Living subjects who don’t want books to be written about them have at least one simple means of damaging, if not halting, publication: refuse to co-operate, and tell friends to do likewise.

In the case of one of the most popular playwrights of the past half-century, Alan Bennett, there has been no authorised biography, and it seems unlikely that there will ever be one. The only attempt at an unauthorised life, Alexander Games’ 2001 Backing Into The Limelight, was stymied by Bennett’s continued refusal to cooperate with his would-be biographer. (The Guardian damned it with faint praise upon publication by calling it ‘a cuttings job with running commentary…not a bad book.’) The only occasion that the two met was a rainy evening near Bennett’s home in the Eighties, by chance. Games announced his appreciation for Bennett and his work, and the playwright, understandably disconcerted by this, replied ‘Thank you for your support’, and disappeared into the night.

Yet Bennett does not seem entirely averse to being written about. Not only has he published several volumes of memoir and diaries himself, but he donated his papers and archive to the Bodleian Library in 2008 for free, pointedly distinguishing himself from his fellows who sold their work to wealthy American institutions for vast amounts of money. Theoretically, anyone could visit Oxford and begin research into his life with infinitely more resources than the unfortunate Games was ever blessed with.

Bennett’s peer Tom Stoppard has himself been the subject of two volumes of biography. They are an acclaimed and exhaustive authorised biography by Hermione Lee published last year and which drew on numerous interviews with him, and an unofficial book by a Canadian academic. It led Stoppard to comment in one interview, with amusement, that ‘he’s called Ira something or other and keeps turning up like a character from a Christopher Isherwood novel…I’ve told him that he’s on his own.’ The book, entitled Double Act, was soon out of date, with several major plays and screenplays not covered.

Stoppard also said in the interview, as far as I’m aware, I’m not hiding anything.’ Given Lee’s scrupulously detailed revelations about some of his personal life, including an alleged long affair with Jeremy Irons’ wife Sinead Cusack, this was a disingenuous statement, at best. But it is the unfortunate role of the biographer of the living to be part-detective, part-therapist and, if the subject becomes angered by revelations or suggestions, more than part-lawyer, too.

Scobie and Durand’s biography of Harry and Meghan won’t make much of a dent on the biographical form or its canon; books of its nature are ephemeral and soon forgotten once the breathless headlines disappear. But biographers should think carefully before attempting to cover living subjects, unless they have reached at least retirement age. That way, the result will be considerably more measured, authoritative and complete – and without the need for a six monthly update.

Comments